Competitive Advantage

Performance difference is not the rule in all industries and although differences may exist, they are often short lived. Nevertheless some firms, in many different industries, in many different countries and contexts, are doing better than others.

Competitive Advantage

Understanding the conditions and factors that control over-performance, has taken centre stage in business strategy.

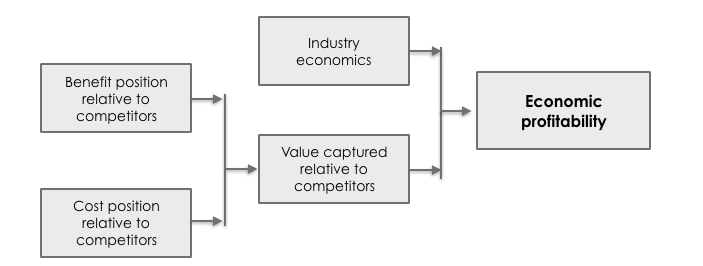

„An enterprise has a competitive advantage if it is able to create more economic value than the marginal (break-even) competitor in its product market, where economic value is the difference between the perceived benefits gained by the purchasers of the firm’s goods or services and the economic cost to the enterprise.” [Peteraf03]

Competitive advantage is obtained when a firm develops or acquires a set of characteristics that allow it to outperform its competitors.

Competition is anyone who can influence a business’ cost or revenues adversely. Puranam16

According to Porter ( [Porter80] [Porter85] [Porter98] ) the choice of competitive Strategy is driven by two central questions (neither is sufficient by itself):

the attractiveness of industries for the long-term profitability (and the factors that determine it)

the determinants of relative competitive position within an industry.

Competitive advantage grows fundamentally out of value a firm is able to create for its buyers that exceeds the firm’s cost of creating it. Porter85

To be successful, firms need to gain a competitive advantage over rival organisations operating in the same business areas. Within the competitive arena chosen by the firm, it needs to accrue enough power to counter balance the demands of buyers and suppliers, to outperform rival, to discourage new firms from entering the business and to fend off the threat of substitute products or services. Preferably, this competitive advantage over other players in the business should be sustainable over a prolonged period of time. [B. De Wit and R. Meyer]

„An enterprise is said to have sustainable competitive advantage when i) it is capturing more economic value than the average firm in its industry and ii) other firms are unable to duplicate the benefits of this strategy.” [Barney, 1991]

A competitive position can usually not be considered sustainable or defensible for ever. Sooner or later, competitors will find ways to match the advantage.

Dominante explanations

Since the early 90’s the academic debate is dominated by the controversy between the two major theories that have been developed by scholars in strategic management, to explain and identify the conditions under which some organisations can create and sustain performance differentials

Market-View Theory: mainly stems from industrial economics and considers that over performance ties in with market power and power negotiation. Over-performance arises from the structure of the market and is deeply rooted into positioning the firm in its product-market arena. Strategic choices must select the market in which to participate and how to position the firm within these markets. The sustainability of the advantage depends from structural barriers (e.g. barriers to entry, barriers to exit).

Resource-Based Theory: offers a wider spectrum of potential sources of over-performance. Distinctive, valuable firm-level capabilities built over time and that competitors are unable to reproduce, support the differential ability of firms. The advantage relies less on the industry structure and more on the specific abilities that a firm can mobilise to respond more effectively and efficiently to customers’ needs. Sustainability is associated with the cost that would incur less efficient firms to copy the most performant firms.

The central research research question for strategic management is to understand “why do some firms persistently outperform others” [Barney, 2007]

Practitioners, for their part, not only seek to understand the origins of outperformance but try also to find ways to maximise the performance of their organisation. Indeed they are not interested in making predictions only, but also seek to make prescriptions.

The Market View of the firm

The market-based theory of the firm derives from micro economics and industrial organization, in particular from the structure, conduct and performance developed by Bain ( [Bain54] ) . A vast strategic management literature has been devoted to that model, initially articulated by Michael Porter ( [Porter79] ) who is among the most prominent figures associated with the market-based theory of the firm and competition.

Competition is at the core of the success of failure of firms. Competition determines the appropriateness of a firm’s activities that can contribute to its performance. Porter85

According to the proponents of the market-view, competition is central and is and at the core of economic exchanges: „ Competition is one of the society’s most powerful forces for making things better in many fields of human endeavour ” ( [Porter2008b] ) . In all his writing, Porter strongly advocates the freedom of unrestricted development in all spheres of human activities and for instance notes that „ Competition has spread all sectors of society worldwide and now embraces fields like the arts, education, health care and philanthropy ”.

As stressed in ( [Magreta11] ) to succeed a firm shall not seek to be the best but rather to become unique.

Two ideas are central to Porter’s beliefs and theory:

Strategy is about being different: Porter argues that competitive strategy is about being different, which requires deliberately choosing a different way to deliver a mix of values (i.e. to perform different activities than rivals or to perform activities differently). Outperforming rivals requires establishing and maintaining dissimilarities.

Strategy is about saying no. A now classical saying in strategy is: „ you can’t be everything to everybody ”. What is meant is that firms must decide which business they’re in. Then they should focus on that business only. If necessary they should have the courage to turn off some activities / customer groups that do no longer fit their strategy.

To Porter, Strategy is a set of deliberate, consistent and relevant actions that explain why some firm can sustainably over-perform.

Companies are in strategic competition when they choose to adopt different paths.

The success of a company shouldn’t depend on the failure of its competitors. [Magreta 11]

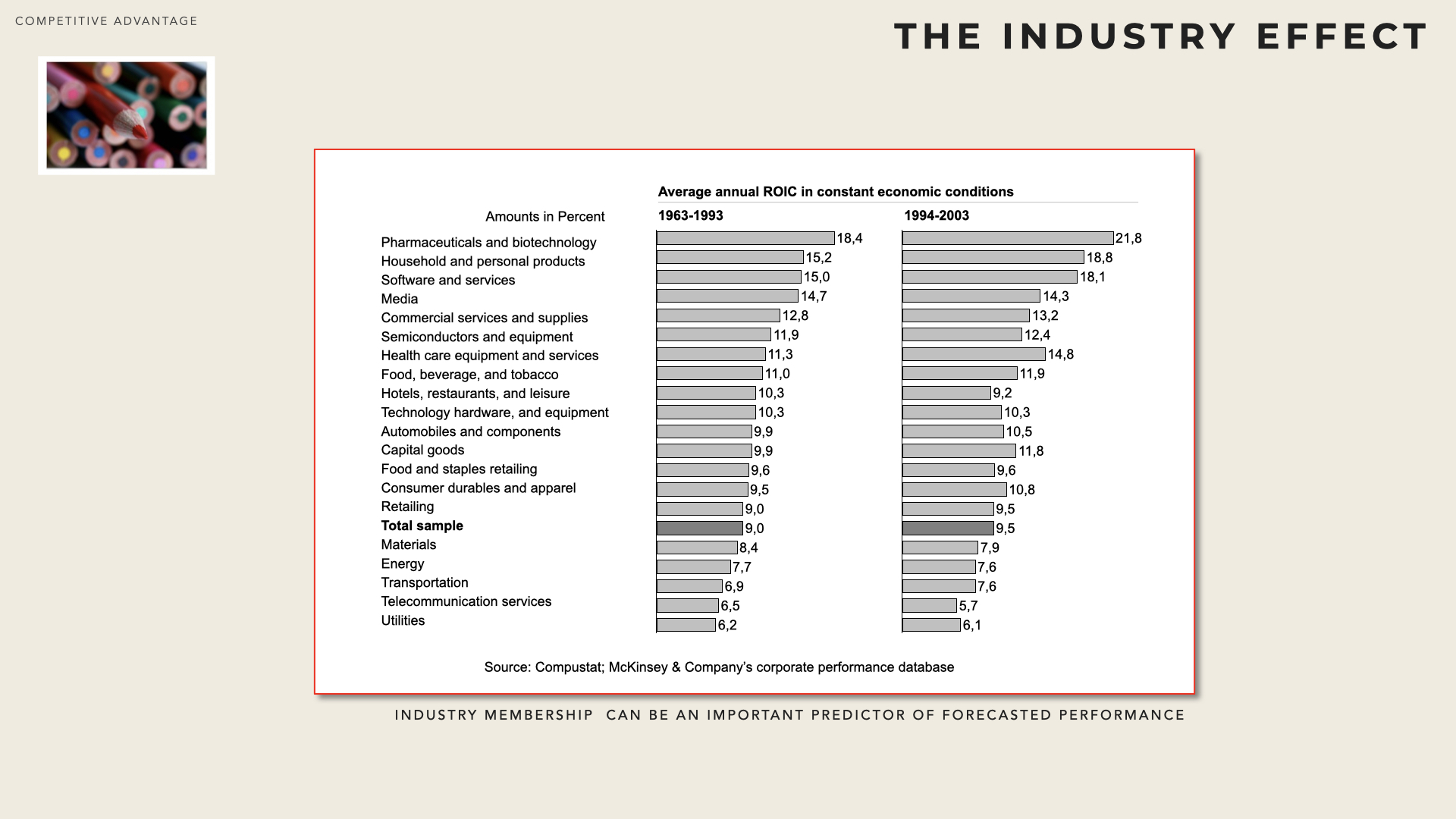

According to Porter, the two major factors that influence how profitable individual firms will be are the industry structure within which they compete and how they position themselves against that structure.

Does operational excellence contribute to strategy?

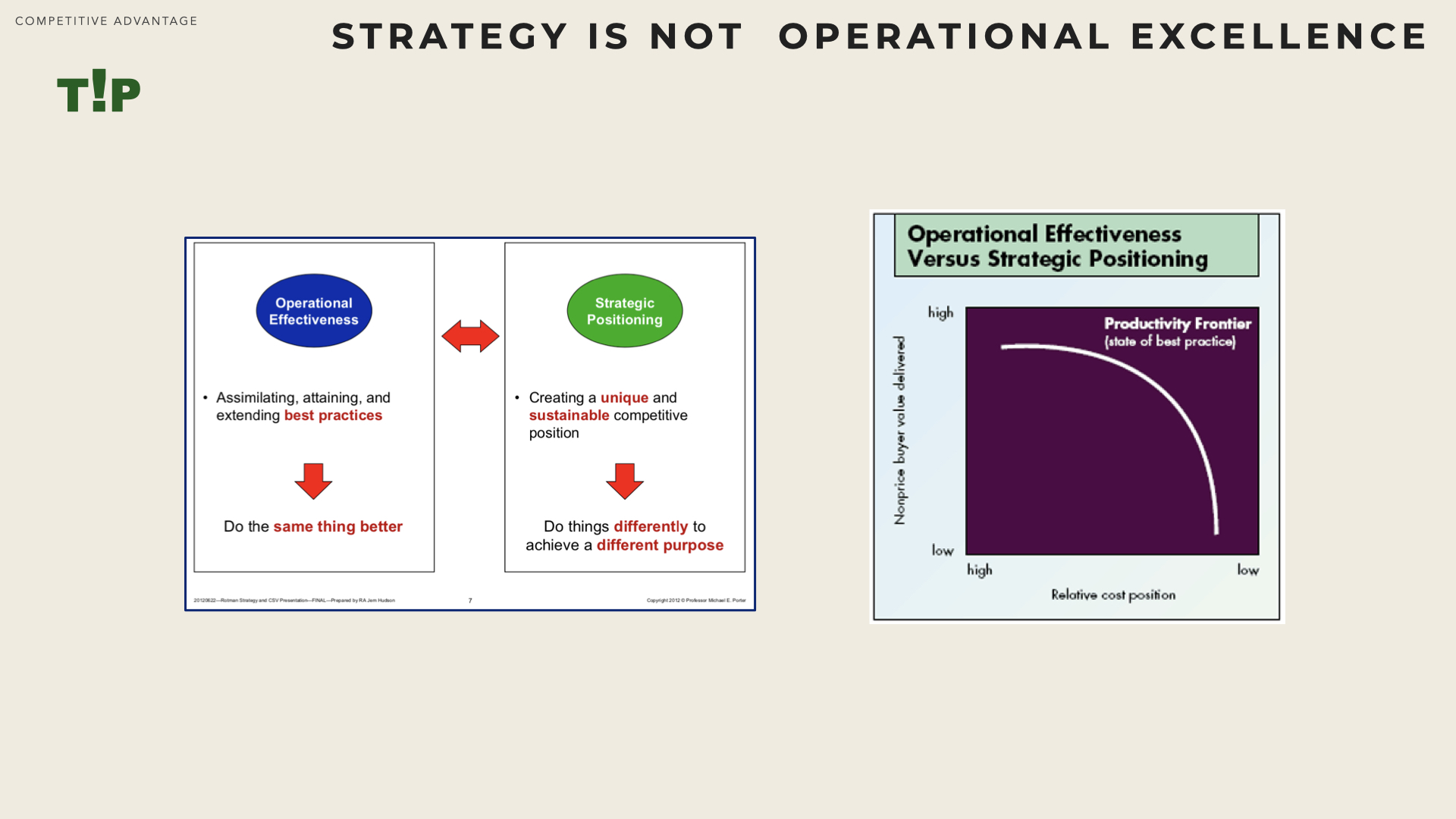

In a famous article ( [Porter96] ) Porter insists that although Operational Excellence contributes to superior performance, it should not be confused with Strategy. In his views, both operational effectiveness and strategy are essential to superior performance but the two approaches work in completely different.

Operational effectiveness aims at performing similar activities better than rivals. By contrast, strategic positioning entails

„Operational Effectiveness is about doing more for less while Strategy is about being different: performing different activities from rivals’ or performing similar activities in a different ways” [Porter].

Porter calls productivity frontier the sum of all existing best practices at any point in time. This is the best value a company can produce at that time. However the productivity frontier is constantly shifting outward with the introduction of both new technologies and new management approaches. Operational Excellence produces absolute improvement in productivity, which generates relative improvement for no firm (all the gains are captured by customers, technology providers, advisers and consultants).

Operational Excellence leads to Strategic Convergence

Alone Operational Excellence leads to strategic convergence (level playing field – all companies become identical). Indeed any improvement gets quickly copied and imitated by competitors. By focusing on operational effectiveness only, firms are contesting a race down identical paths. To the extreme, industry consolidation is the only way to escape massive value destruction.

Is Lean Management a strategy ?

It became obvious in the 80’s, that the performance of Japanese factories was by far overshooting any American and/or European standard. Despite their lower production volume, they were delivering higher profitability and better quality with lower inventory levels, less space and much faster throughput.

For the proponents of the Market-View theory, Lean Management is not a strategy. The founder of the Boston Consulting Group declared : „until the causes of the differences can be explained the underpinnings corporate strategy are suspect” (Bruce Henderson).

Over time Toyota created systems that continually worked on eliminating all unnecessary work (“non-value adding work” or waste) thereby incurring less total costs, and using capital more productively that its competitors. The common denominator of all Toyota’s efforts is time. [O. Fiume - “Lean is a Strategy”]

For most lean experts however, Lean Management as introduced by Toyota (Toyota Management System) leverages time to differentiate from competitors.

The Industry Effect

Porter has created various analysis frameworks that establish fundamental logical relationships:

to be more profitable than others, a firm need to sell at a higher price or to produce at a lower cost;

competition within an industry depends on five-forces

a firm is characterized by a set of activities.

«In essence, the job of the strategist is to understand and cope with competition. Competition for profits goes beyond established industry rivals to include four other competitive forces as well : customers, suppliers, potential entrants and substitute products. The extended rivalry that results from all five forces defines an industry’s structure and shapes the nature of competitive interaction within an industry. […] The point of industry analysis is not to declare the industry attractive or unattractive but to understand the underpinning s of competition and root cause of profitability » – [Porter,1979].

Frameworks to further analyse and understand external & internal factors will be detailed in the section that deals with Value Architecture.

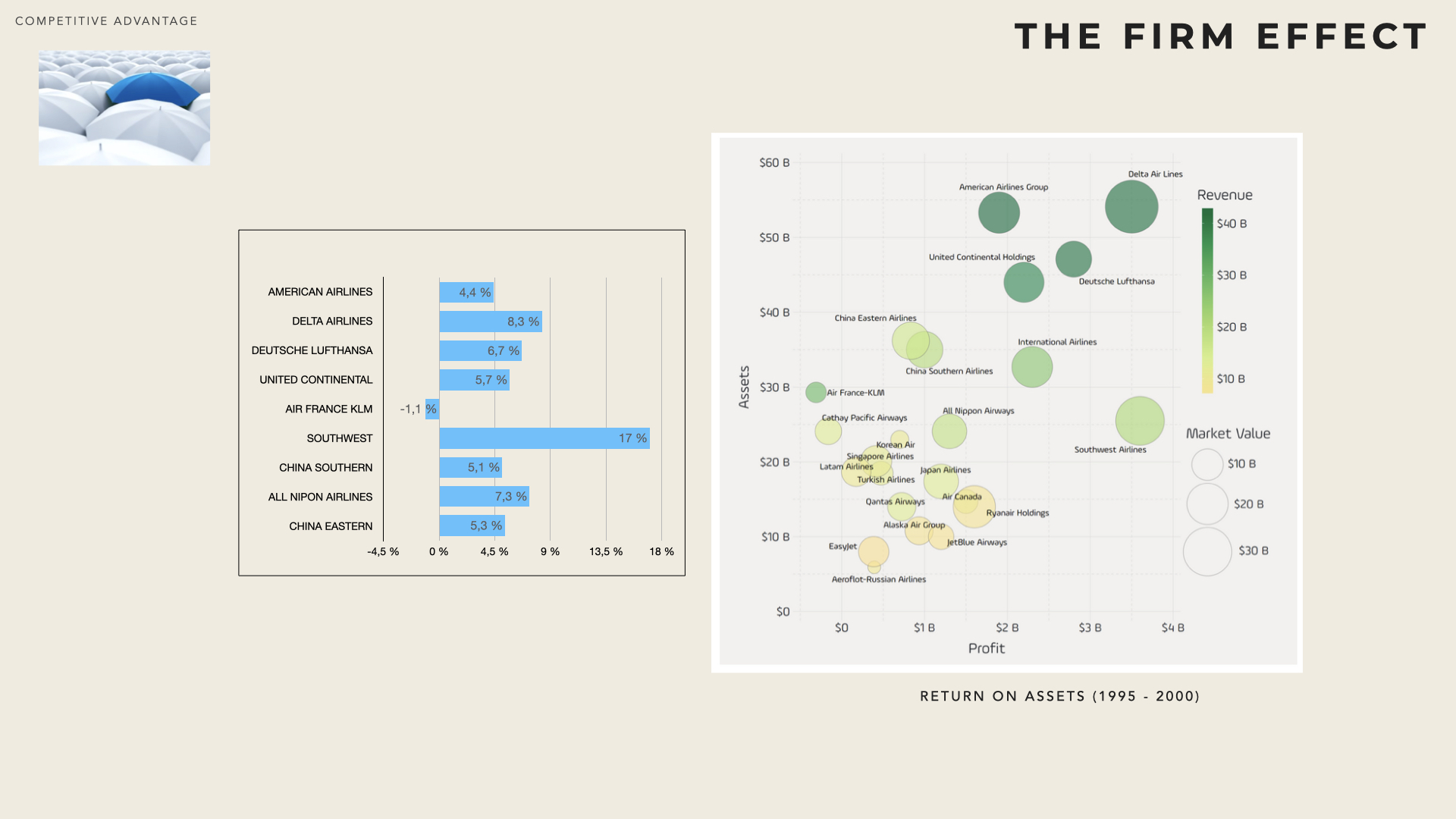

The firm effect

The industry and its structure, don’t alone explain the performance of firms. Indeed, within a same industries, performance can significantly varies across firms.

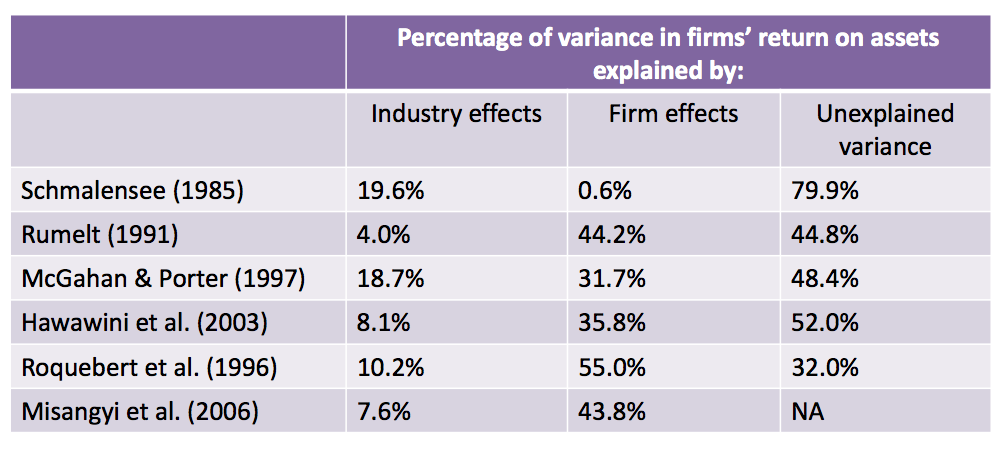

Grant ( [Grant91] ) mentions several studies performed by different scholars that sought to establish the respective importance of the industry and firm effects respectively. None of the analyses are considered as decisive. Still it shows that although there is undoubtedly an industry effect, it is usually not fully explaining the overall performance.

Barney ( [Barney91] ) underlines that the market-view of the firm focuses on competitive imperfections in product markets to explain persistent differences in firm performance. The 5-forces framework (see later) is for instance, one of the most prominent tools to underline such imperfection and identify opportunities to earn superior returns. However, whether a firm can gain a competitive advantage doesn’t depend solely on strategies that create competitive imperfections in product markets but as well on the total cost of implementing these strategies (which is determined by the competitiveness of the strategic factors).

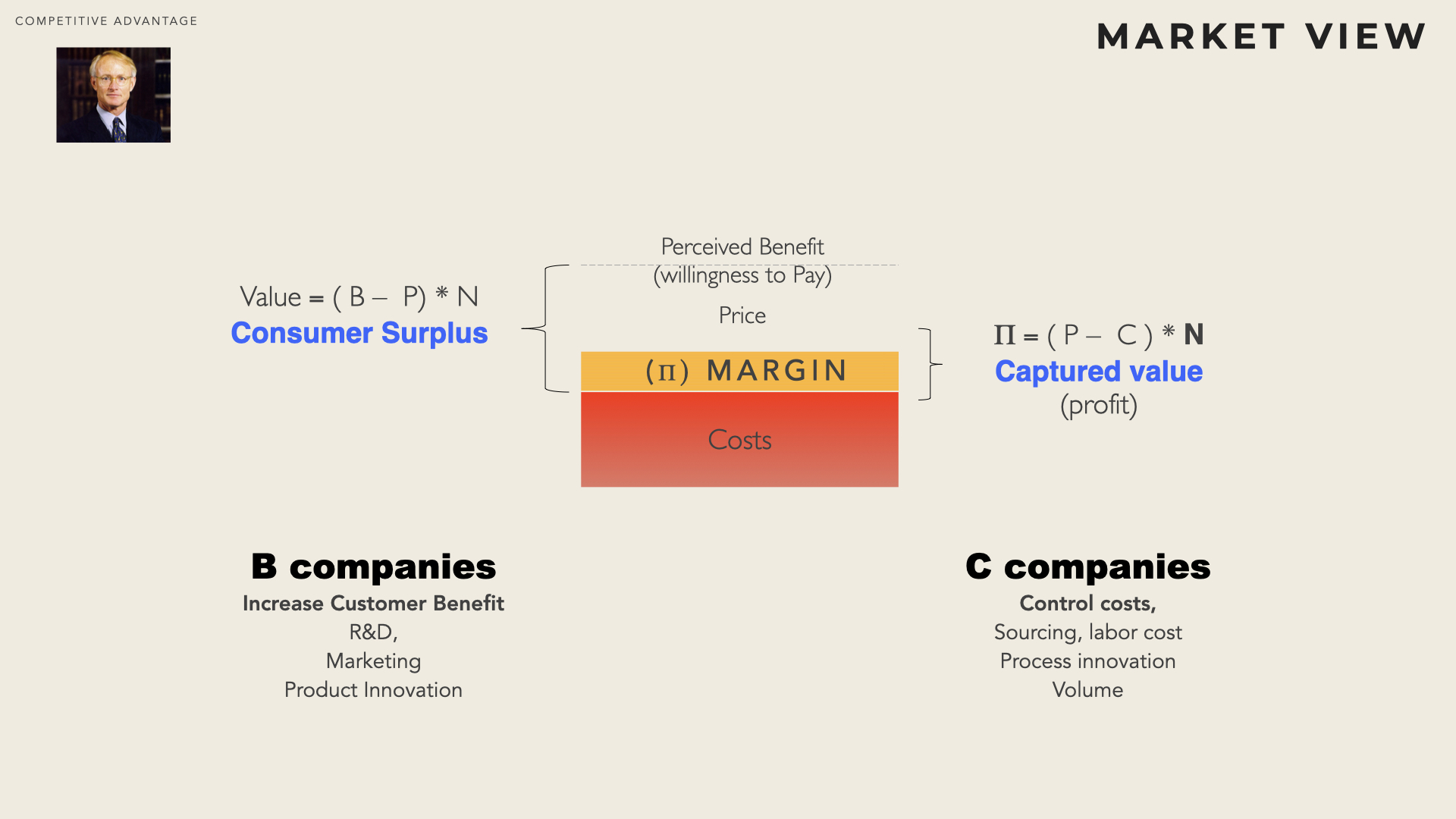

The total created value is (not necessarily equitably) shared between the Customer’s surplus (transferred to the customer) and and the captured value kept by the firm.

Porter’s Generic Strategies

To be competitive at all, a firm must ensure that all its customers see sufficient value so that they are prepared to purchase its products and services at a price that exceeds the costs of supply. In addition, if the firm has a advantage it becomes able to claim more value than its competitors.

As stated by Besanko, a firm can generate more economic value than others by either i) configuring its value chain differently from competitors or ii) by performing activities better than rivals, while configuring its value chain essentially as all the others.

For Porter and the Positioning School there are two fundamental ways, to set a firm apart from its competitors and build an advantage:

Differentiation delivering greater value to customers in exchange for a premium. There are fundamentally three sources of differentiation : product attributes (innovation, quality), pseudo-differentiation (advertising, brand notoriety) and geography.

Cost leadership creating comparable value far more efficiently than competitors. A firm undergoing a cost leadership strategy will be characterised by very thigh cost discipline and will for instance, seek to benefit from economies of scale and scope.

In addition, Porter adds a further dimension subject to the scope that the business choses to serve. Indeed a company can either focus on narrow customer segments or target broad range of customers.

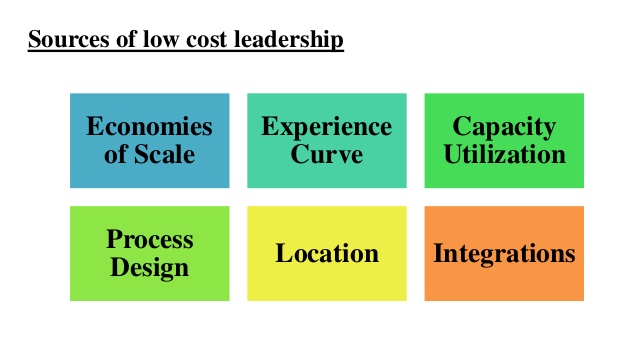

Cost Leadership

A firm seeking to undergo a cost leadership strategy, will concentrate on the following drivers:

Reduce input costs labor, raw materials, procured components. The firm is also likely to consider relocating some activities to low cost countries.

Seek economies of scale increase production volume to reduce the ave- rage cost per unit (e.g. fixed costs amortisation, …).

Seek experience effect speed-up production ramp-up and steepen the learning curve which improve staff productivity. Early entrants may gain an advantage. Likewise firms gaining and holding the highest cumulative volume are better off.

Design Process Approaches such as DFM (Designed for Manufacturing), DFA (Designed for Assembly), Lean management, Six Sigmas to optimise workflow & process efficiency.

Cost leadership implies having the lowest costs in the industry. There can be only one cost leader per industry. Firms shouldn’t pursue a cost leadership strategy in total disregard for quality. They basically have two options:

Parity in service /product. The firm offers a product/service that has the same perceived value than other products in the market, trades at the same price but can be produced at a lower cost. The cost advantage translates into extra profit compared to the average firm.

Proximity The firm decides to downgrade some characteristics of the product which allows for far more efficient costs while not translating into large price cut.

Differentiation

A differentiation strategy involves uniqueness along some dimension, that is sufficiently valued by customers to allow a price premium. Various competitors may select different dimension and therefore there might be more than one differentiation strategy.

Usually differentiation comes at a cost (e.g. additional R&D, additional capex, branding, customer care, etc). Firms however, must check that their customers are ready to pay the product/service in excess to these additional costs.

It should be underlined that a higher perceived value means that (some) customers recognise that the product/service is superior and are are willing to pay more for it. This should not be confused with offering a different value proposition which may not necessarily yield higher prices.

Focus Strategies

A focus strategy targets a narrow segment of a domain of activities and tailors its products and services to the needs of that specific segment to the exclusion of any other.

The focuser achieves competitive advantage by dedicating itself to serving its target better than any other competitors can do. For instance, Ryanair targets price sensitive passengers with no need to connecting flights.

Successful focus strategies depend on:

Distinct Segment Needs should the distinctiveness of the segment erode, the advantage of focussing would vanish. For instance, RIM initially targeted its BlackBerry at business users. As there are no longer any difference between a mobile phone for business purpose and for general purpose, RIM has lost its advantage and is struggling to stay in business.

Distinct Value Chain addressing distinct customer groups with different means (i.e. more efficiently that what non-focussed competitors would do).

Viable Economic Segment to be successful, a focus strategy must tackle a business segment that is large enough. The demand must be sustainable and solvent.

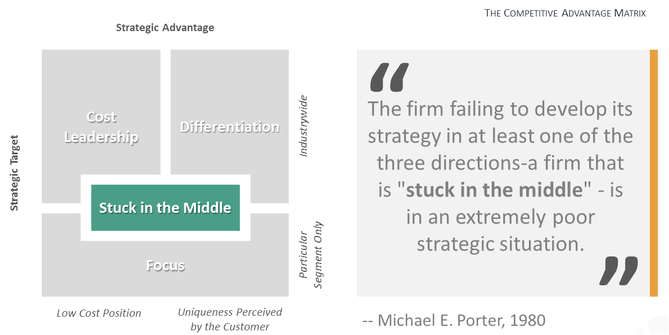

Stuck in the middle

According to Porter, firms must choose between the three generic strategies. Any attempt to compromise and combine more than one generic strategy would result in destroying company value.

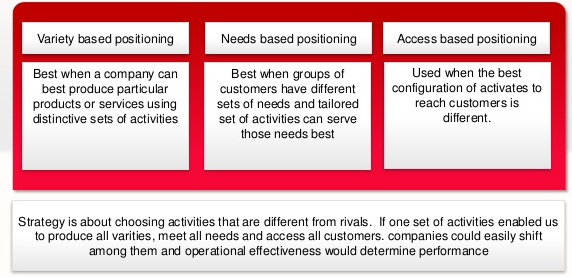

Complement: Porter’s Positions

At a more detailed level, strategic positions emerge from three sources ( [Porter98] ) that are not mutually exclusive and often overlap.

Variety-based positioning produces a subset of an industry’s products or services. It is based on the choice of product or service varieties rather than customer segments. Thus, for most customers, this type of positioning will only meet a subset of their needs. It is economically feasibly only when a company can best produce particular products or services using distinctive sets of activities.

Needs-based positioning serves most or all the needs of a particular group of customers. It is based on targeting a segment of customers. It arises when there are a group of customers with differing needs, and when a tailored set of activities can serve those needs best.

Access-based positioning segments customers who are accessible in different ways. Although their needs are similar to those of other customers, the best configuration of activities to reach them is different. Access can be a function of customer geography or customer scale or of anything that requires a different set of activities to reach customers in the best way.

The Resource-Based Theory

The Resource-based model results from the contributions of several pivotal scholars such as ( [Amit93] [Barney91] [Barney97] [Penrose59] [Peteraf93] [Pisano] [Teece97] [Wernerfelt84] ) and was initially formalized by Barney in his seminal article of 1991.

By contrast to the market-view of the firm, the RBT – Resource-Based Theory aka Resource-Based View of the firm – makes two assumptions in analysing sources of competitive advantage:

Firms within an industry (or a strategic group) may differ with respect to the strategic resources they control.

These strategic resources may not be perfectly mobile among firms and therefore heterogeneity can be long lasting.

A resource is ‘any asset, capability, organisational process, firm attribute, information, knowledge that enables a firm to fulfil the activities in its value chain’ - ( [Puranam16] )

The proponents of the resource-based view (or Resource-based theory) of the firm, outline that in a fast changing external environment, internal resources and capacities can provide a more secure foundation to long-term strategy.

The RBV is a business performance model focusing on resources and capabilities controlled by the firm (business unit) as a main source of competitive advantage and performance. Dynamic Capabilities View (Di Stefano, Peteraf, & Verona, 2010; Drnevich & Kriauciunas, 2011; Helfat & Peteraf, 2009; Teece, 2007; Teece, et al., 1997), a recent and promising development within the field, is sometimes considered as an extension of RBV framework (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000).

With the market-based view, also known as the outside-in or positioning approach, firms see themselves through the industry and market they serve. The key strategic questions are ’what is our business?’, or ’what are the customers’ needs that we fulfil?’. By contrast, the resource-based view of the firm adopts an inside-out approach and focuses on the firm’s internal capabilities: ‘what are our specific skills and capabilities?’ - ‘what do we do better than the others?’.

For RBT, resources are “ the stock of available factors that are owned or controlled by the firm ” ( [Amit93] ) and strategy becomes the continuing search for rent or return in excess of a resource owner’s opportunity costs, where owning a competitive advantage can drive above normal rates of return.

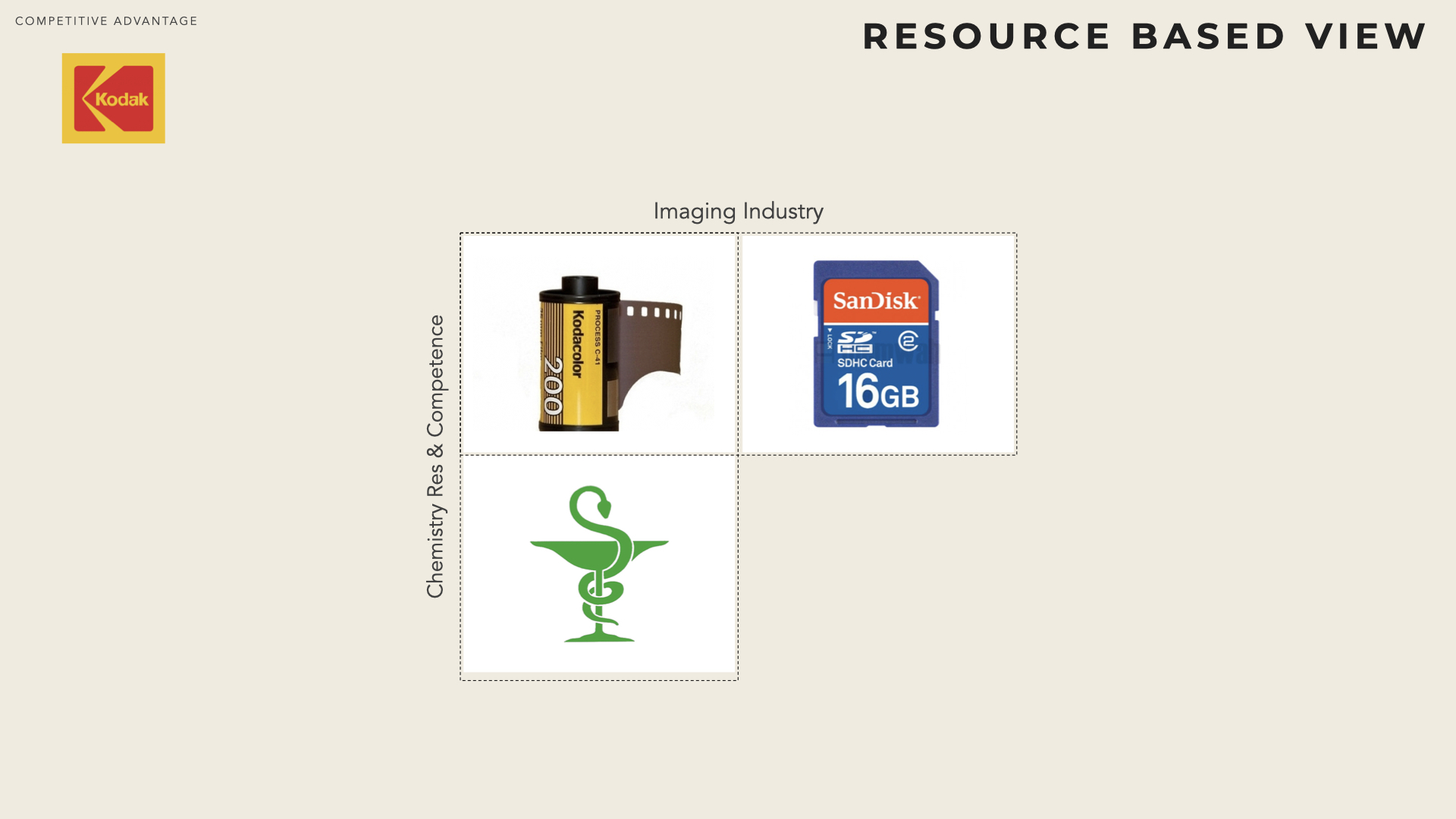

Example: the Kodac Case

KODAC was the undisputed leader in chemical imaging photographic products. However, with the introduction of a superior product (digital photography) returns dropped quickly. In response, KODAC decided that coping with this new substitute would be its number one strategic priority

For years, Kodak has unsuccessfully invested billions to fight against emerging technologies and to transpose its leadership to digital imaging, considering it was still the same industry and it wanted to restore its leadership position.

Grant raises the question : „might have KODAK been better-off sticking with its chemical know-how and developing its interest in specialty chemicals, for instance, pharmaceuticals or healthcare” ([Grant, 2006]).

Example: Google seats in various industries

Google was established in 1998 as a web search engine company. In this ’industry’ Google faced Yahoo, Bing and other similar firms specialised in indexing and retrieving web pages.

Soon, Google extended its activities and entered other industries (then facing new competitors) such as software applications (Maps, Chrome, Google Apis), operating systems (Android), Web content & social networks (Google news, Google+, gmail), application and data hosting (Google cloud).

In the words of Larry Page & Sergey Bin the co-founders, Google’s mission is „to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. Google doesn’t see itself through either the markets they address (it may change over time) or their competitors. On the contrary, they define themselves by a set of capabilities.

Key Assumptions of the theory

Organisation are not identical:

they have different capabilities, in other words resources are heterogeneously distributed among firms (i.e. not all firms own all resources). Scott ( [Scott08] ) stresses that the relevance of a resource is highly contextual and depends in particular on the selected business model. A resource can be key to one firm and just not fit with another within the same industry.

Resources are imperfectly mobile (i.e. resources stick with their owner) and therefore differences between organisations are rather stable. This explains the existence of differences across firms in resource endowments and why this differences may persist over time [Barney 91].

A competitive advantage (superior performance of a firm) is explained by the distinctiveness of its capabilities. Acquiring specific capabilities is usually a long and costly process. In addition, it may be difficult to establish a causal relationship between a level of performance and a set of capabilities.

The Resource-based model hinges upon the assumptions that i) a firm can hold a competitive advantage if it controls and exploits capabilities that are both valuable and rare, ii) a firm can sustain this advantage if capabilities are inimitable and non-substitutable and iii) this translates into long-term over-performance.

The resource-based approach helps explaining why a company possesses a competitive advantage (single business) and/or a corporate advantage (in the set of businesses it operates).

„While a competitive advantage may be achieved by luck, a sustainable advantage requires a resource and competence-sensitive strategy process” ([Barney, 1986]).

Although the wording may vary among academics (and also among practitioners) the model hinges upon the concept of a specific bundle of resources that a firm has built up and accumulated over time (resources are stocks of assets and capabilities). Firms are therefore constrained by the resources they possess but also protected if it takes time for competition to copy their very resources.

The resources & competences framework can be used to scan the various businesses in which a firm could develop a competitive advantage, based on its existing capabilities. Likewise it may highlight the capability gaps in a given business.

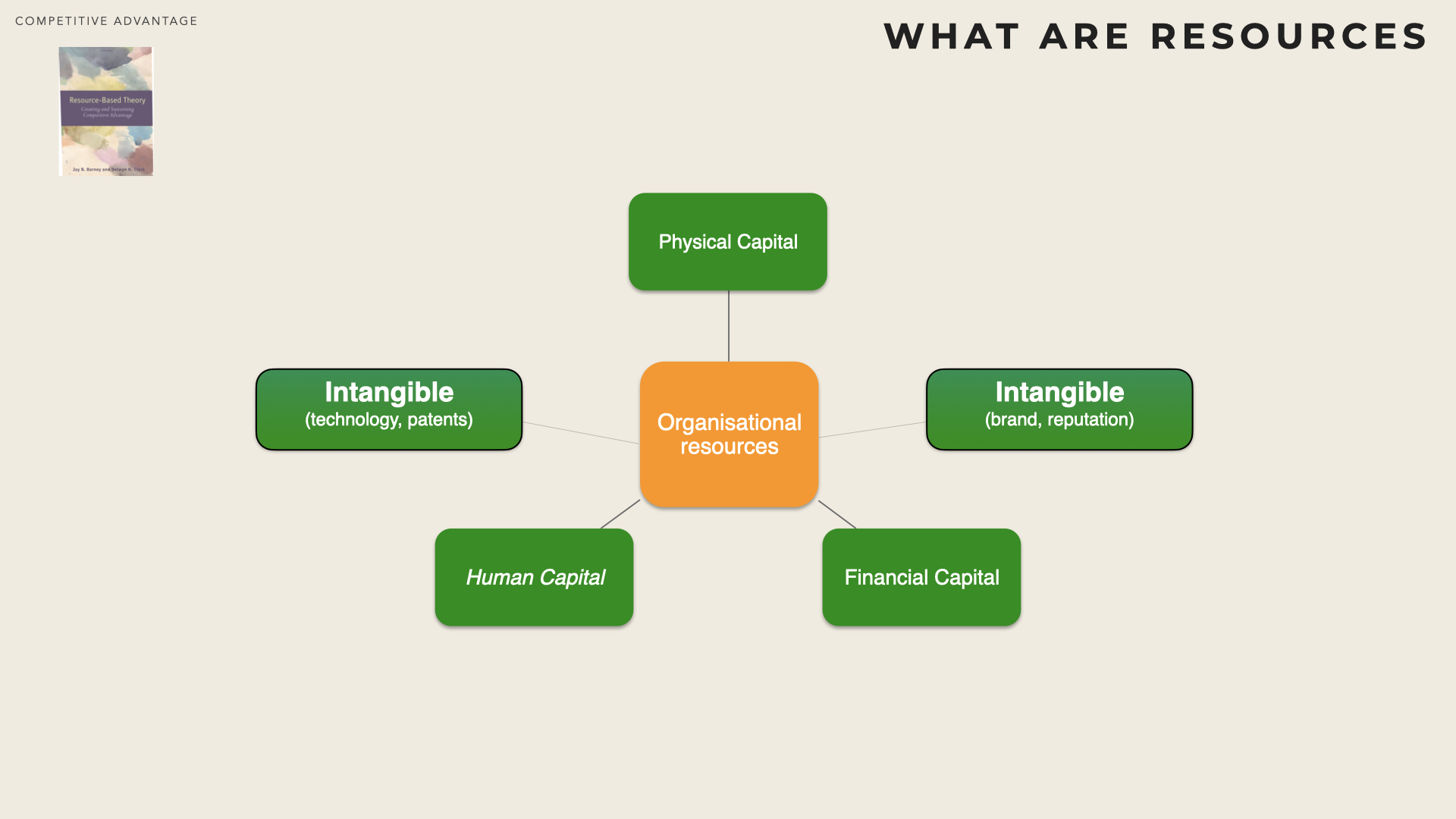

There are fundamentally four categories of resources:

Physical capital geographical location, plants, machinery and physical technology,

Financial capital equity, debt, access to debt market, rating,

Human capital training, experience, insight, judgment,

Organisational resources firm culture, reporting structure, formal and informal planning, controlling, reputation

„A firm’s ability to earn a rate of profit in excess of its cost of capital depends upon two factors: the attractiveness of the industry in which it is located and its establishment of competitive advantage over rivals. Business strategy should be viewed less as a quest for monopoly rents (the returns to market power) and more as a quest for Ricardian rents (the return to the resources which confer competitive advantage over and above the real costs of the resources).” ([Grant, 1991])

Resources may be thought of as inputs that an organisation possesses or can call upon (e.g. from suppliers) to carry out its activities. Resources can be i) tangible (cash, geographical location, buildings, machinery and equipment, land, mineral reserve,), ii) intangible (technology, patents, copyright, brand name, reputation and notoriety, brands, customer, relationship, culture) or iii) human (skills, know-how, motivation, organizational capabilities, company culture).

A resource is something that the firm holds and can use to generate value. A resource can be viewed as a productive asset that the firm controls. The tangible, physical resources usually appear on the balance sheet of the firm. By contrast, accountants don’t measure other resources except in case of acquisition (where some resources can ’indirectly’ be recorded as ”Goodwill”).

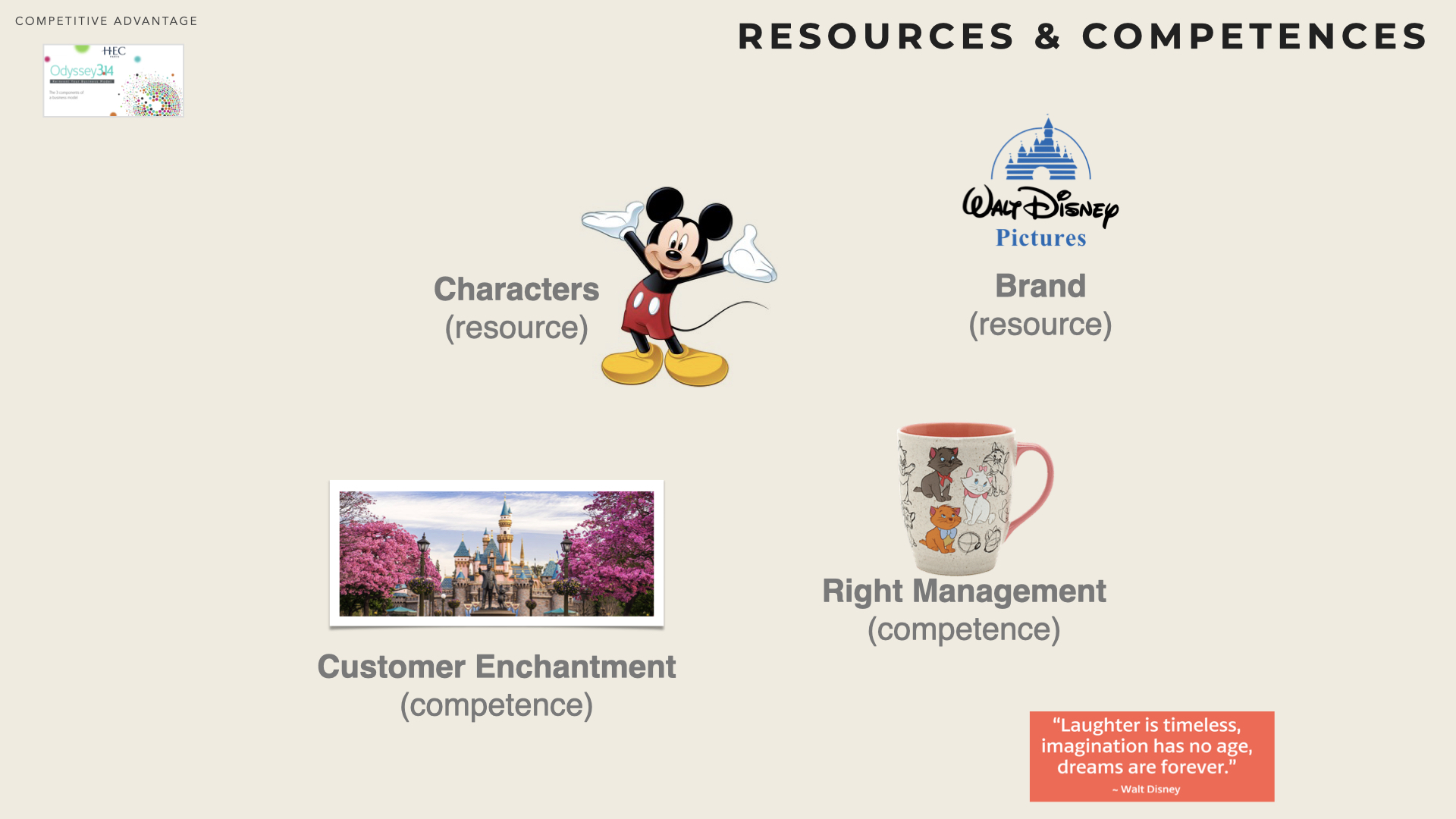

Resources & Competences

Two broad types of capabilities are usually considered :

Resources are the assets that a firm owns or can call upon (including ties with partners and suppliers). Resources are basically what a firm possesses.

Competences are the way those assets are used or deployed effectively. That is what a firm does well with what they have.

Strategists look in priority for businesses where the existing resources & competences (i.e. that the firm already controls) can be exploited. This is often the reason why firms consider, in priority, diversification in adjacent domains (leveraging the existing customer base or extending the existing products to additional customer groups and hence benefit from economies of scale/scope).

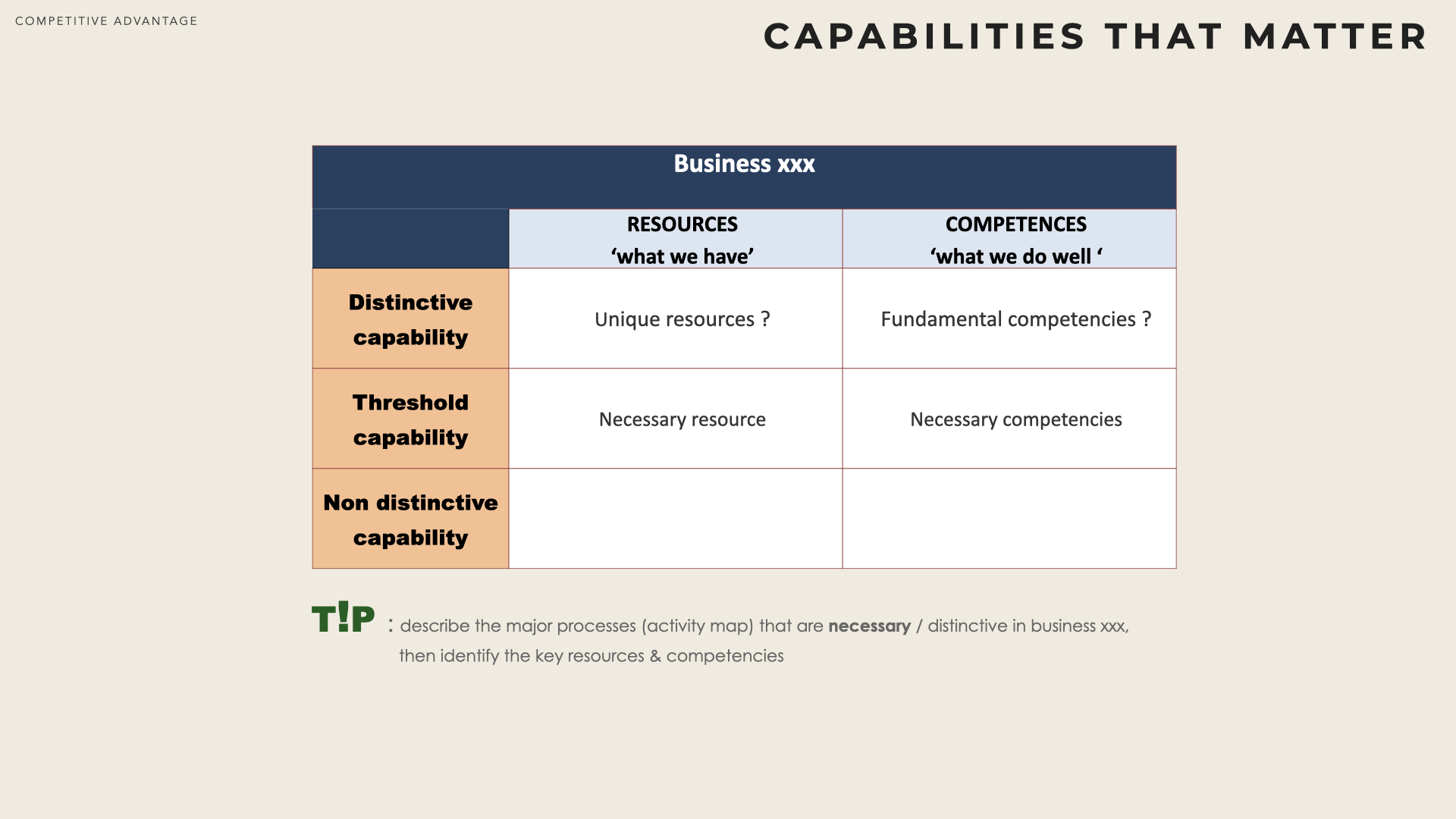

A Strategic Capability (resource or competence) contributes to the long-term survival or competitive advantage of an organization.

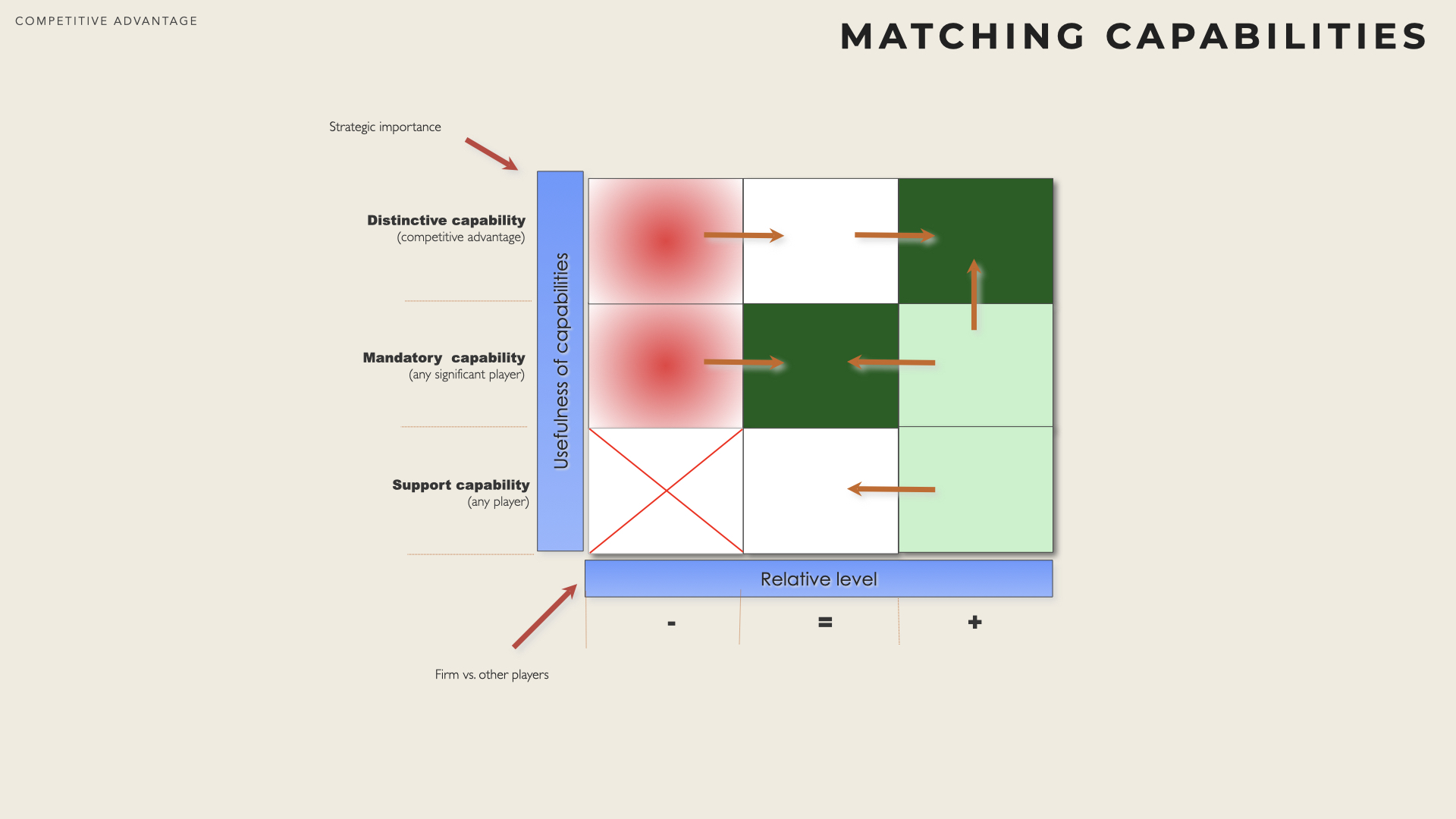

Managing Capabilities

The difference between the capabilities that must be controlled to become a significant player and the capabilities already controlled by the firm is a way to measure the level of matching (or strategic fit). However, the analysis must not be limited to systematically filling a grid, but on the contrary to highlight the few capabilities that are decisive to enter a business and generate sustainable profits.

A Threshold Capability is the capability level needed to meet the necessary requirements to exist in a given market and/or establish a business.

A Distinctive Capability is the capability level that may be the basis of achieving competitive advantage and delivering superior performance.

When gaps are identified (and there are usually gaps), the firm can explore various options to fill them. First, the firm can try to develop ”in-house” additional capabilities (acquire the missing resources, learn new competence). The firm can also look for other companies that could be complementary and bring the missing capabilities through alliances, partnerships or merger

According to the RBT, the basis of competitive advantage may lie in aspects of the organisation that are difficult to discern or be specific about. However capabilities are highly dynamic (competitors may manage to copy or imitate a set of capabilities) and therefore they must be carefully and proactively managed. Firms have fundamentally three options to manage strategic capabilities:

Internal capability management a firm may decide to reinforce its existing capabilities. This includes i) leveraging capabilities from one area of the business to others and ii) stretching capabilities i.e. build new services / products out of existing capabilities.

Growing capabilities through external developments such as M&A and/or Strategic alliance building.

Ceasing activities when the gap becomes too high or the advantage too narrow, a company may be better off exiting this specific area of business and refocussing on other domains.

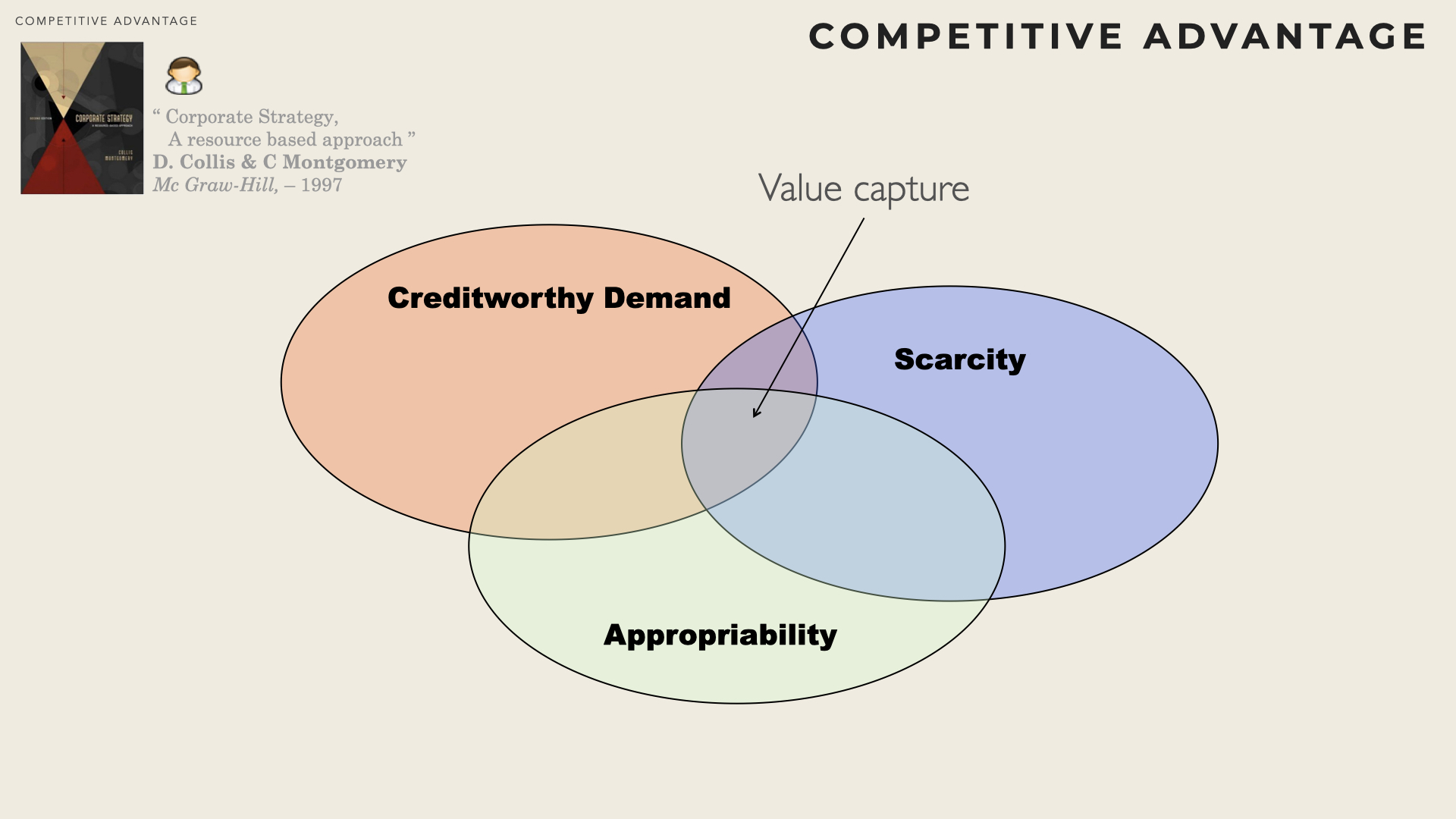

Capturing Value: The Collins & Montgomery’s Framework

Collins & Montgomery ( [Collins95] ) consider that ”Value creation” lies at the confluence of demand, scarcity and appropriability. Value is created when a resource is demanded by creditworthy customers, when it can barely be replicated by competition and when the firm can easily capture the profit it generates.

„the challenge for manager is understand what distinguishes valuable from pedestrian resources and to use that knowledge to craft strategies that generate an enduring competitive advantage.” [Collins Montgomery]

Creditworthy demand

A resource is valuable to the extend that is meets customers’ demand and allow to serve customers better than competition. Although it sounds obvious, firms tend to forget that a valuable resource must help meeting customer demand and fulfilling a customer’s need at a price the customer is willing to pay.

An analysis of a firm’s resource should therefore not focus on an internal assessment only but also clarify how the firm’s stock of resources translate into fulfilling customers’ expectation better than competition. In addition, as both customer demand and alternate value proposition may evolve, firms must reassess periodically the value of their resources and try to anticipate losses of value.

„A resource value derives from its application in product market. It traces back from the ultimate satisfaction of customers”* [Peteraf & Bergen]

„A resource is valuable if it can generate in someway a rent stream from a product market that can be captured by the firm. A valuable resource must contribute or be involved in the creation of a product or market that has value to customers” [Bowman].

Scarcity

However, not all the resources that contribute to meeting customers’ demand can provide a competitive advantage. The condition is necessary but not sufficient. If the resource that the firm possesses is not in short supply of if it can be easily copied or replicated by competition, it is unlikely that it can yield any competitive advantage. Resource scarcity is therefore the second requirement for a resource to contribute to competitive advantage.

According to Collins & Montgomery there are four characteristics that make resources rare and difficult to imitate.

Physical uniqueness – geographical location, patent, mineral extraction rights, etc. Although firms believe they are well protected against competition when the hold physically unique resources, it however often turns out that such resources are easier to imitate or substitute than expected.

Path dependency – most resources needs to be gradually accumulated over time (brand name recognition, R&D knowledge, organisational capabilities, etc). Imitators usually need to re-create the path that predecessors took, which protect the first-entrant by delaying imitation. However, when the actual valuable resource is easy to identify, imitator may catch up quickly with the pioneering company.

Causal ambiguity – external observers can usually infer some correlations between competitive advantage and resources but may fail to disentangle what the truly valuable resource is.

Economic deterrence – occurs when i) resources are scale sensitive (e.g. capex) ii) the market leader has the capabilities to replicate its resources (e.g. factory) but iii) choses not to do so as market demand is limited. If in addition the resources are specific to a given market (sunk costs), they represent a ’credible commitment’ that the leader will remain in the market and react to any newcomer attempting to enter the market

Value Capture

Meeting customers’ demand and resource inimitability are good ingredient to generate value. However a firm will usually also seek to appropriate and capture value and avoid that somebody else can claim most of the value.

When property rights to the resources are clearly established, profits will flow to the owner of the resources. For this reason, firms are more likely to appropriate profits from the resources they develop themselves than from those they purchase in the market. However there is always a risk that the firm has to pay out its profit to some of its stakeholders (e.g. high salaries to general managers, salesmen, …).

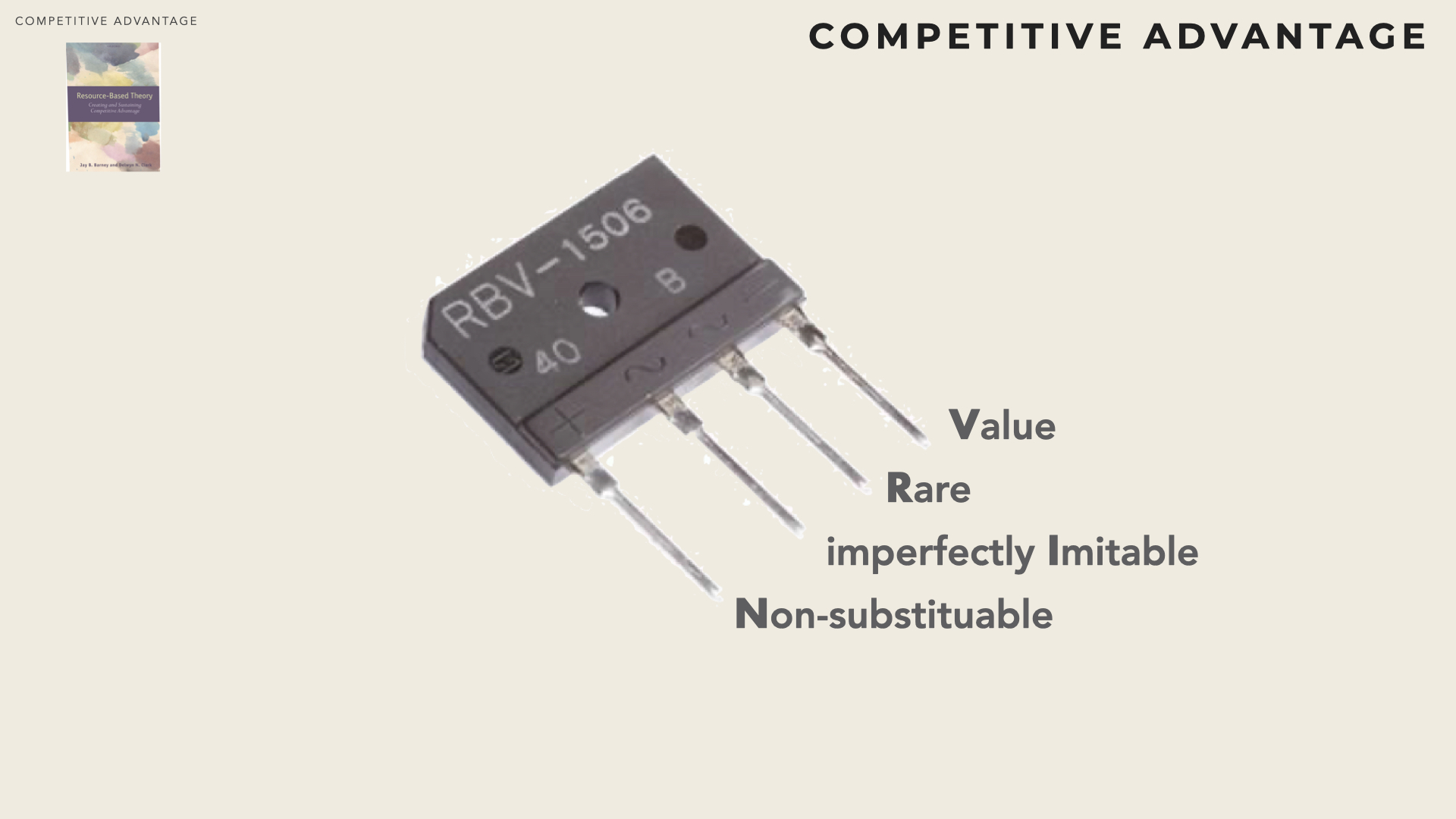

Capturing Value: The VRIN Framework

Barney ( [Barney91] ) put forward the popular VRIN checklist to identify whether or not a capability can be strategically important. It underlines on what bases organizational capabilities might become the foundation for sustainable competitive advantage and superior economic performance.

Valuable

Obviously a resource (or capability) would be of little use if it doesn’t deliver acceptable return to the firm. A firm should not keep a resource that is not (and cannot be made) valuable. According to the RBV literature, valuable resources are resources that allow a firm either to claim for a premium pricing or to lower its cost compared to its competitors. Barney considers that a valuable resource must enable a firm to do things and behave in a way that lead to higher sales, lower costs, higher margins or in other ways add value to the firm. In other words, resources are valuable when they enable a firm to either improve its efficiency or effectiveness. A valuable resource must allow either exploiting opportunities and/or neutralising threats.

Note : when assessing whether or not a resource is valuable, the key question must be ’valuable for what’ (indeed, a resource can barely be valuable in absolute terms, even the concept of ’resource’ is not absolute).

Rare

A firm enjoys a competitive advantage when it creates more economic value than its average competitor. If a valuable resource is highly available among competitors then it is unlikely that it can be the source of any significant advantage. A bundle of resources can generate a competitive advantage as long as the number of firms that can use these re- sources is low compared to the total number of firms in that particular industry. Capabilities that are owned by a large number of firms cannot confer competitive advantage, indeed if competitors have similar capabilities they can quickly respond to any strategic initiative. A Capability that is not rare can still be necessary ; it won’t be considered strategically important though.

Inimitable

Valuable and rare resources can only be a source of sustainable competitive advantage if the average player cannot easily replicate or obtain these resources: the cost of getting a resources should exceed the likely economic profit it would yield. Otherwise, any competitive advantage will be short-lived. Barney outlines three reasons why resources would be imperfectly imitable (or costly to imitate):

ability to obtain the resource is dependent on unique historical conditions (including first-mover advantage or ripple effect from resources acquired in the past)

link between the resource and the advantage is causally ambiguous (i.e. it is not easy to understand which are the resources that yield the advantage and this is often true of the firm that enjoys the advantage. Indeed very often managers consider some resources as implicit and cannot easily outline the firm’s recipe for outperformance. For instance because some intangible assets – e.g. teamwork – can be hidden and/or because a complex network of interrelated intangible and organizational resources is at play)

resource (capability) is socially complex - which includes interpersonal relationships ; a firm’s culture, a firm’s reputation among its peers, its suppliers and customers.

Non-substitutable

There must be no strategically equivalent valuable resources that are themselves neither rare nor inimitable. It is generally argued that to achieve strategic advantage from a capability it needs to be developed internally and should not be freely traded in the market. In- deed, if a valuable, rare and imperfectly imitable resource can be easily substituted by a set of resources that would yield similar effects while being easy to duplicate and/or easy to acquire at low cost then it is unlikely that any competitive advantage can be long lasting.

The VRIO Framework

Before being re-dubbed ’VRIN’, Barney’s framework was known as ’VRIO’ where ’O’ stands for Organised.

The thought behind stressing that a firm had to be aligned with its own strategy was that possession or control of VRIN resources is necessary but not sufficient to gain an advantage. Indeed the firm must be ready to leverage its re- sources and capture value. This encompasses capacities such as incentive and monitoring systems, formal and informal reporting , interface and collaboration among customer facing and support Functions. In other words, a firm that possesses a valuable and rare resource will not gain a competitive advantage unless it can actually put that resource to effective use.

„ For instance, for many years Novell had a significant competitive advantage in computer networking based on its core NetWare product. In high-technology industries, remaining at the top requires continuous innovation. Novell’s de- cline during the mid- to late 1990s led many to speculate that Novell was unable to innovate in the face of changing markets and technology. However, shortly after new CEO Eric Schmidt arrived from Sun Microsystems to attempt to turnaround the firm, he arrived at a different conclusion. Schmidt commented : ”I walk down Novell hallways and marvel at the incredible potential of innovation here. But, Novell has had a difficult time in the past turning innovation into products in the marketplace.” He later commented to a few key executives that it appeared the company was suffering from ’organizational constipation’. Novell appeared to still have innovative resources and capabilities, but they lacked the organizational capability such as product development and marketing, to get those new products to market in a timely manner.” (Stephen Laughnet - Principles of Management)

This example stresses how much it is important to ’start with the end in mind’ and thoroughly identifies all the resources that are needed. A fantastic research lab with track records in unveiling breakthrough technology (e.g. the Palo Alto Research Centre invented the laser printer, the graphical user interface, the mouse device, the ethernet and tons of other technologies) is a rare resource, but if the objective is to deliver innovative product to the market (i.e. capturing value from the innovation) then producing innovation is just half-way to the target. Once all the capabilities (or resources) are identified, the firm must look for ways to derive a sustainable competitive advantage, that is ensure that at list some of the resources are rare, imperfectly imitable and non-substituable. It is paramount to understand that an uncorrelated bundle of VRIN resource is usually yielding no value at all.

Complement: the development of the RBT

The initial development of the Resource-Based Theory (RBT) of the firm ( [Wernerfelt84] [Wernerfelt95] ) was aimed a re-stating Porter’s results from a different perspective (hence the initial name Resource-Based ’View’).

In 1984, Wernerfelt published an article where he suggests that Porter’s theory of competitive advantage could be restated from the assumptions that firms develop or acquire capabilities. In this perspective the resource-based view of the firm is a dual representation of the market-based view. While Porter had focussed on barriers and mobility constraints among industries, Wernerfelt’s intuition was that the competitive advantage a firm enjoys in the market had to be tied to some internal resources it controls, has acquired or developed. Indeed, the Resource-Based View considers that a competitive advantage derives from specific resources & competences controlled by the firm. RBV sees a firm as a set of resources and capacities that can get configured to over perform competition, hence leading to competitive advantage. Therefore the RBV does not point at the industry structure but at the unique cluster of resources and capabilities that each organization possesses and/or want to develop.

The same year, Rumelt published a paper where he establishes a theory of firm performance, rooted in the resources that a firm controls and its capacity to generate economic rents. To a large extend he also considers the conditions under which a firm would be the adequate way to generate and capture economic rents as opposed to other form of organization (this is also the question addressed by Williamson through the Transaction Costs theory, although from a different angle).

Teece merged the two theories and argued that the relations among business that are the most likely to be a source of economic profit (resource-based theory) are also the kinds of relations that are difficult to manage through non-hierarchical forms of governance (opportunism risk associated with transactions costs).

As highlighted by Grant ([Grant, 1991]) the development of the Resource-based theory as an alternative to the market view, may be an answer to fast changing customers needs: „In a world where customer preferences are volatile, the identity of customers is changing and the technologies for serving customer requirements are continually evolving, an external focused orientation does not provide a secure foundation for formulating long term strategy. The firm’s own resources and capabilities may be a much more stable basis on which to define its identity” ( [Grant91] ) .

In 1986, Barney showed that if firms would acquire strategic factors from a perfectly competitive market then this market would anticipate the performance that these factors would bring when used to implement product market strategies. In such an event, even imperfectly competitive product market would no longer be the source of economic rents.

Itanami (1987) introduced the concept of invisible assets (information-based resource, technology, customer trust, brand image, control of distribution, corporate culture and management skills). He considers that while physical assets are necessary, invisible assets are the source of outperformance because they are hard and time-consuming to accumulate.

The resource-based theory encompasses several branches and school of thoughts, each with its own specific field of study and objective.

| Approach | Main authors | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Resource-based view | Barney, Wernerfelt | Delineate and nurture ‘VRIN’ resources to generate sustainable competitive advantage. |

| Core Competence | Hamel and Prahalad Amit and Schemaker |

Delineate, focus and exploit core competences. Derive product/market presence from the core competence of the firm. |

| Dynamic capabilities | Teece Pisano and Schuen |

Optimally and purposefully adapt capabilities as to better match the evolution of market demand, products and technologies |

| Evolutionary Theory | Nelson and Winter | Adapt and refresh the internal routines and organization of firms. |

Competence or Capabilities

Essentially, RBT conceptualises the firm as a bundle of resources. It is these resources, and the way that they are combined, that makes firms different from one another and in turn allows a firm to deliver products and services in the market. However resources in themselves do not confer any value to organisations. Resources have a potential use but alone are unproductive and do not confer any value in themselves to organisations. Value generation requires combining the adequate resources and the necessary skills. Competences are the most intangible and correspond to the activities, modus operandi and processes through which a firm can effectively use its resources. A competence is what a firm does well.

Organisational capability requires the expertise of various individuals to be integrated with capital equipment, technology and other resources (e.g. a brain surgeon if of little value if not complemented by an hospital, surgical instruments and equipment, a full team of skilled people, etc).

„There is a key distinction between resources and capabilities. Resources are inputs into the production process but on their own few resources are productive. Productive activity requires the cooperation and coordination of teams of resources. A capability is the capacity for a team of resources to perform some task or activity. While resources are the source of a firm’s capabilities, capabilities are the main source of its competitive advantage” ([Grant, 1991]).

Specific capabilities correspond to the (possibly unique) technologies mastered. Capabilities are activities that the firm does particularly well compared to competition. For instance, CANON offers a large spectrum of apparently uncorrelated products: camera, printers, fax-machines, copy-machines, video camera, etc. In all these products, a few fundamental capabilities are paramount: precision mechanics, micro-electronic and fine optics.

Likewise, 3M built its impressive product portfolio (in excess of 30.000 products) on the foundation of i) a few key technologies: adhesives, thin-film coatings and ii) the ability to market and launch new products. (adapted from [Grant, 2006])

Jon Kay ( [Kay95] ) distinguishes three fundamental types of distinctive capabilities:

Architecture comprises the system of contracts and relationships between the firm and its ecosystem (employees, customers, partners, suppliers, distributors, etc). Organisations depend far less on individual leaders than they do on their established structures, dominant styles and organisational routines (ways of working). Often, the relationships will be implicit and complex, with little formalisation if any. In markets where the quality of products is derived from long-term experience, reputation is usually also a source of distinctive capability.

Reputation brand notoriety, customer’s experience, quality signals, word of mouth spreading, etc. A well managed reputation can be extended to new products

Innovation new technologies, new processes, introduction of new pro- ducts, but also finding applications for existing underused technologies (e.g. 3M derived post-it notes from low-quality adhesive).

Distinctive capabilities are necessary but not sufficient for success. Capabilities must also be sustainable – it needs to persist over time – and appropriable (i.e. to benefit primarily to the organisation rather than its employees, its customers or its competitors). A sustained competitive advantage occurs when an organisation is implementing a value-creating strategy that is not being implemented by current or potential competitors and when these competitors are unable to duplicate the benefits of the strategy. A competitive advantage may get eroded as the industry changes but won’t get competed away by competitors

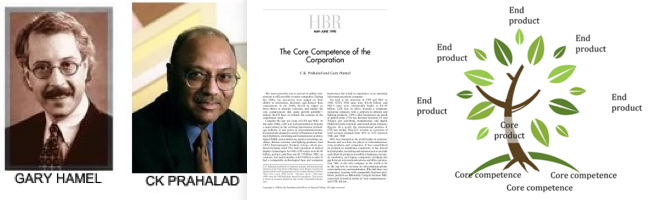

Core Competence

Prahalad and Hamel ( [Prahalad90] ) call core competence any competence that a firm masters particularly well, compared to its competitors.

In their view, a ”Core competence” i) should provide access to a wide variety of markets (e.g. Honda’s capabilities in engine design - cars, lawnmowers, powerboats), ii) should make a significant contribution to the perceived customer benefits of the end products (e.g. BMW, excellence in engineering) and last but not least, iii) it should be difficult for competitors to imitate.

In addition, for a core competence to have any lasting value to the organisation the competitive advantage that derives from its use must be sustainable. In their seminal paper, Prahalad and Hamel emphasise that „in the short-run a company’s competitiveness derives from price/performance attributes. However competitors are all quickly converging on similar standards for product cost & quality. […] In the long-run competitiveness derives from an ability to build , at a lower cost and more speedily than competitors, the core competence that spawn unanticipated products”.

The real sources of advantage are to be found in management’s ability to consolidate corporate wide technologies and production skills into competencies that empower individual business to adapt quickly to changing opportunities.

Core competencies are the collective learning in organisation, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies. Unlike physical assets that do deteriorate over time, competencies are enhanced as they are applied and shared (knowledge also fades away if it is not used). Competencies are the glue that binds existing business and are also the engine for new business development. Pattern of diversification and market entry can be guided by competencies and not just by market attractiveness.

Dynamic Capabilities

The ability of a firm to renew and recreate its strategic capabilities and meet the needs of changing environments, is in itself a key strategic resource. Indeed capabilities that are the basis of competitive success soon get copied by competitors and become standard practice of the industry. To continue to be effective overtime, capabilities can’t remain static but on the contrary need to adapt. By and large, three categories of dynamic capabilities can be identified: i) ability to sense new opportunities, ii)ability to seize an opportunity (i.e. to make a choice) and iii) ability to re-configure the firm’s capabilities.

More than the list of capabilities that a firm controls, what matter is the relative level with respect to competition in the capabilities that significantly contribute to the realization of the core business. When the firm is short of some capabilities, the management must create an imbalance (what Hamel & Prahalad call “stretch & leverage”), that forces the company to increase its capabilities to become more efficient and effective relative to competition.

Competitive advantage as a result of rents

The strategic management literature considers that broadly speaking there are two sources of superior profitability:

industry attractiveness which stems from market power, barriers to entry, etc and can be assimilated to what economists call monopoly rents. It is earned by a firm that enjoys a legally enforced or de facto monopoly (i.e. is the only firm to satisfy some customers’ requirements) and is also contingent on demand elasticity, which depends on the availability of substitutes.

scarce resource control (firm-specific assets such as patents, trademarks, brand reputation, distribution channel, key technologies, installed base, etc) that economists call Ricardo rents, earned by a firm that possesses valuable and rare factors.

innovation that can generate what economists call Schumpeterian rents during the period of time between the introduction of an innovation and its successful diffusion (and until it gets imitated).

The superior performance of a firm arises from sustainable competive advantages that are the result of either monopoly rents, Ricardian rents or Schumpeterian rents (Peteraf93, Powell01, Wang14)”

To economists „A a rent is any payment to a factor of production (i.e. resource) in excess of its opportunity cost” [Krugman 16]

Ricardo Rent

Ricardo rents are often considered as the tangible materialisation of a competitive advantage.

„The Law of Rent states that the rent of a land site is equal to the economic advantage obtained by using the site in its most productive use, relative to the advantage obtained by using marginal (i.e., the best rent-free) land for the same purpose, given the same inputs of labor and capital” * (D. Ricardo, An Essay on the influence of a low price of corn on the profits of stock, 1809)

David Ricardo, a British economist, introduced the concept with an example borrowed from agriculture.

Let’s consider the business of growing wheat and assuming that ’land’ is the only significant factor of production. Back in the XIX century it was indeed the case as i) labor-cost was insignificant ii) there was very little capital investment in farming i.e. no agricultural machinery, duty trucks and iii) operating expenses such as fertilizers, pesticide, etc were inexistent.

At first, only the most most fertile parcels of land are under cultivation. At a certain point, all such land is used and population increase force into cultivation inferior lands: additional crops are seeded on less fertile parcels to meet the new demand. The cost to produce one unit of crop in inferior lands is superior to the cost of producing the same quantity in superior lands. On the market, however there will be only one price (that needs to be greater than or equal to the cost of production on inferior land). This counterintuitive result (raising the total quantity produced will cause the price to also raise) illustrates that the best lands (scarce resources) will benefit an extra return (the difference between the cost of production in superior and inferior lands).

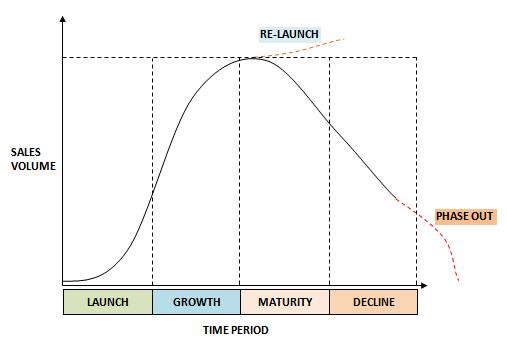

Industry Lifecycle

Any thorough analysis of an industry should take into account the stage of development of that industry.

At least four stages should be considered:

Launch (or initial development, or product introduction): the industry is still experimental in many ways. It usually consists of very few players with very differentiated products. There is little direct rivalry. Even if the industry doesn’t collapse, it is very likely that not all players will make it to the next stage.

High Growth rivalry remains low as the market offers high opportunities. If barriers to entry are low, new players will be attracted which will increase rivalry.

Shakeout demand approaches saturation levels. A significant portion of demand correspond to replacement because fewer first-time buyers remain. As firms have been accustomed to high growth they may continue to add capacity at a rate that become inconsistent with actual demand and translates into over capacity.

Maturity the market is totally saturated, demand limited to replacement and the growth rate declines. Rivalry is likely to increase as players can only gain new revenues at the expense of their competitors (zero-sum games) which impact prices. Some players will seek to exit the market which may drive more consolidation of the industry. Barriers to entry will usually increase (and as a result the threat to new entrant is vanishing). Firms that remain in the market will seek to drive their cost down and build strong brand loyalty. Periodic price wars may occur among surviving players

Decline growth become seriously negative and no more investments on products/services (substitution products are getting more traction). Players seek to harvest as much as they can before leaving the industry. The degree of rivalry usually decrease. However if exit barriers are high and the decline is quick, the industry is likely to suffer overcapacity (as in the shakeout phase) which can trigger fierce price wars.

| Stage | Launch | Growth | Shakeout | Decline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb players | Very Few | More | Many | Concentration |

| Product Diff. | Highly differentiated | Converging | Commodity | Commodity |

| Direct Rivalry | low | low | high | low |

| New entries | few | Many | None | Exit |

Strategizing in Mature Industry

A mature industry is characterised by i) limited growth and ii) a bunch of large companies (small and medium companies can co-exist as well but would represent a rather limit cumulated market share).

Entrenched players are very aware of the strategic nature of their interaction. They know that changing any attribute of their business model can trigger a chain of reactions and unbalance the industry equilibrium. As a result, established companies often seek to collectively moderate the intensity of competition (this can not be formally agreed in most countries - antitrust laws - however several signaling mechanisms can be used).

Entry Deterrence

Existing players can deploy several strategies (all these strategies are carefully witnessed by anti-trust authorities) to prevent the entry of new players:

Product proliferation incumbent players attempt to limit new entries by making sure every market segments and market niches is well served (saturated). This prevent potential new players from gaining experience, scale and brand at the lower end of the market and then progressively move upmarket.

Limit price when economies of scale are not sufficient to discourage potential new entrants, incumbent players can (in the short run) charge a price that is lower than the profit-maximizing price to artificially cap profits (and make the industry less attractive).

Technology upgrading incumbent firms can invest in costly technological upgrades to increase upfront investments for new comers if they want to match the same technology level. Similarly, existing players can speed up research and development and launch more advanced products.

Strategic Commitments incumbent companies can signal potential entrants that entry will be difficult by committing significant and long term resources (e.g. sunk costs, investment in excess production capacity, etc). As a result, both the perceived cost and risk of entry will raise and limit the likelihood of new comers entering the industry.

Brand notoriety existing firms can increase their communication and advertising budgets to strengthen their brand at the expense of any potential entrants.

Rivalry Management

Strong rivalry among incumbents usually translate into price erosion which destroys industry profitability. Several techniques are used by companies to limit profitability losses.

Price Signaling the technique is basically a tit-for-tat strategy - price moves (increase or decrease) are copied by all the players. Collusion (an explicit agreement between parties to limit open competition) is usually illegal. However, through price signalling companies can exchange information which enables them to understand each other’s pricing policy and converge toward an homogeneous pricing policy across the industry (that optimises profitability). It can also be a response when a firm decreases its price. The other players will cut their price even more aggressively to stress that the price war initiator stands for more to lose.

Price Leadership the industry waits for the firm with the highest cost structure (the firm that has the smallest margin) to set its price first. Then competitors offering products in the same market segment align their own prices (within a price range).

Non-price competition is a strategy where the value transferred to the end-customer is increased while keeping the price untouched (i.e. avoiding price cutting and price war). This is achieved by asymmetrically increasing the customer’s willingness to pay through product differentiation.

Market penetration is an attempt by one of the existing players to expand its market share (in the existing market). This usually involves aggressive marketing campaigns and advertising to strengthen the brand name. When successful this strategy has a two-fold effect : attracting new customers (from rivals’ customer base) and commanding premium prices.

Product proliferation see above, the largest players will grow their market presence (offer product in all the segments) in a attempt to increase their market penetration (usually at the expense of the smaller players).

Product development (see technology upgrading above) stimulate demand for product renewal by introducing new models (e.g. new car mo- del). This will usually go hand-in-hand with new non-price features. This however can drive the industry profitability down as more and more in- novation & development will be needed.

Market development with this strategy, a company seeks to leverage the notoriety it has developed by starting to compete in new markets/industries (see Corporate Strategy section).