What is Value ?

As we will see later, a value proposition is at the interface between the firm and its customers, it is characterized by a mix of attributes (e.g. price, availability, reliability, technical specifications, image, ease of use, etc…). For a transaction to take place the value proposition of a firm must be valued by a customer (willingness to pay) at a level that exceeds the price requested by the firm.

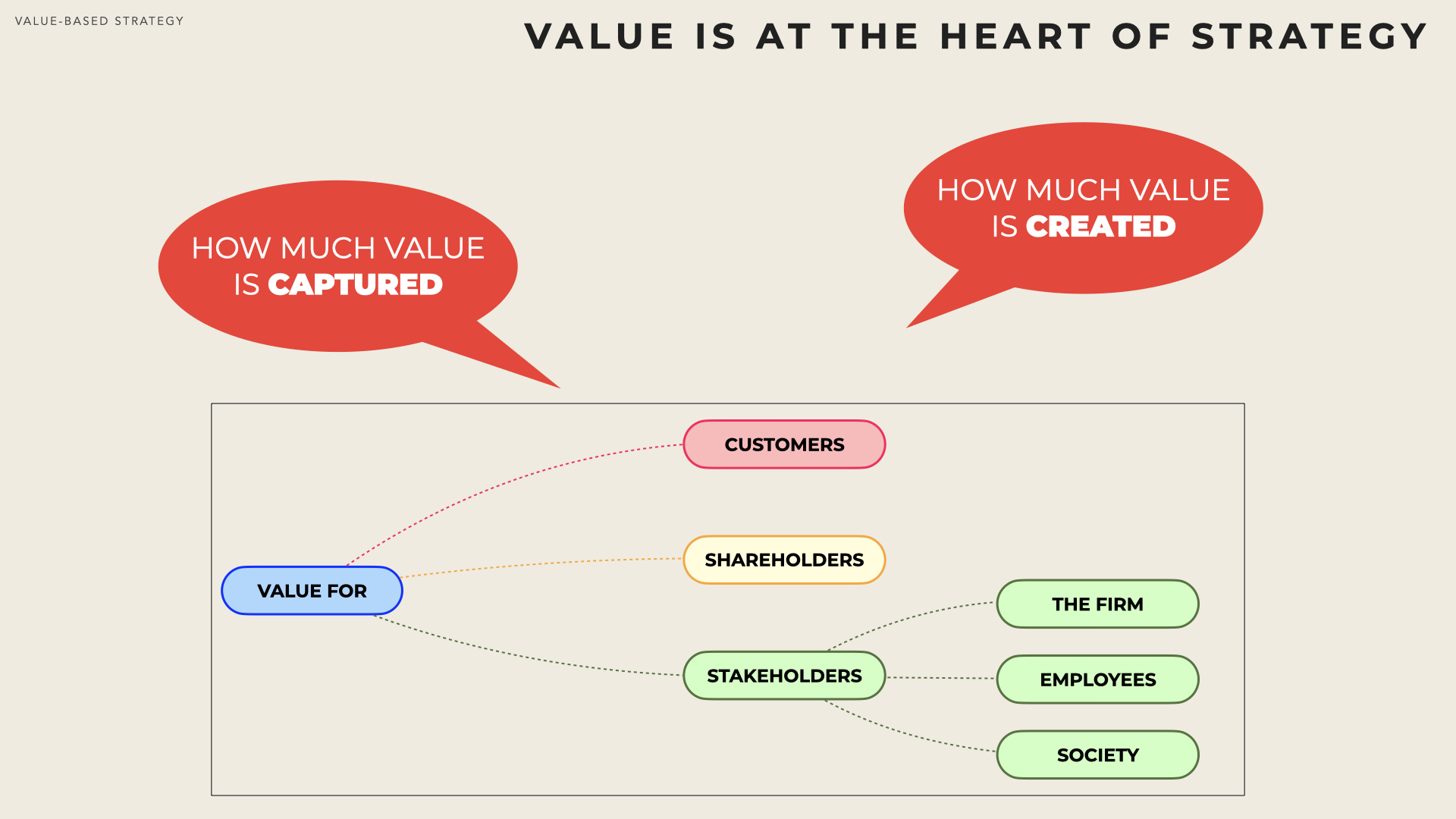

As stated by Peter Drucker: The only valid definition of a business purpose is to create a customer. However, for a business to be sustainable, it must also be profitable and generate some profit. Any firm must design value propositions that meet demand, but it must also adopt a value architecture so that it can generate earnings to reward its owners and debt-holders.

Furthermore, as stressed by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization firms may also seek to combine economic, social and environmental benefits. With strategic management concepts such as Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR), Ethics and Compliance (E&C) and eco-efficiency, firms address more globally their responsibilities toward their environment and stakeholders.

Customer Value

Willingness to Pay

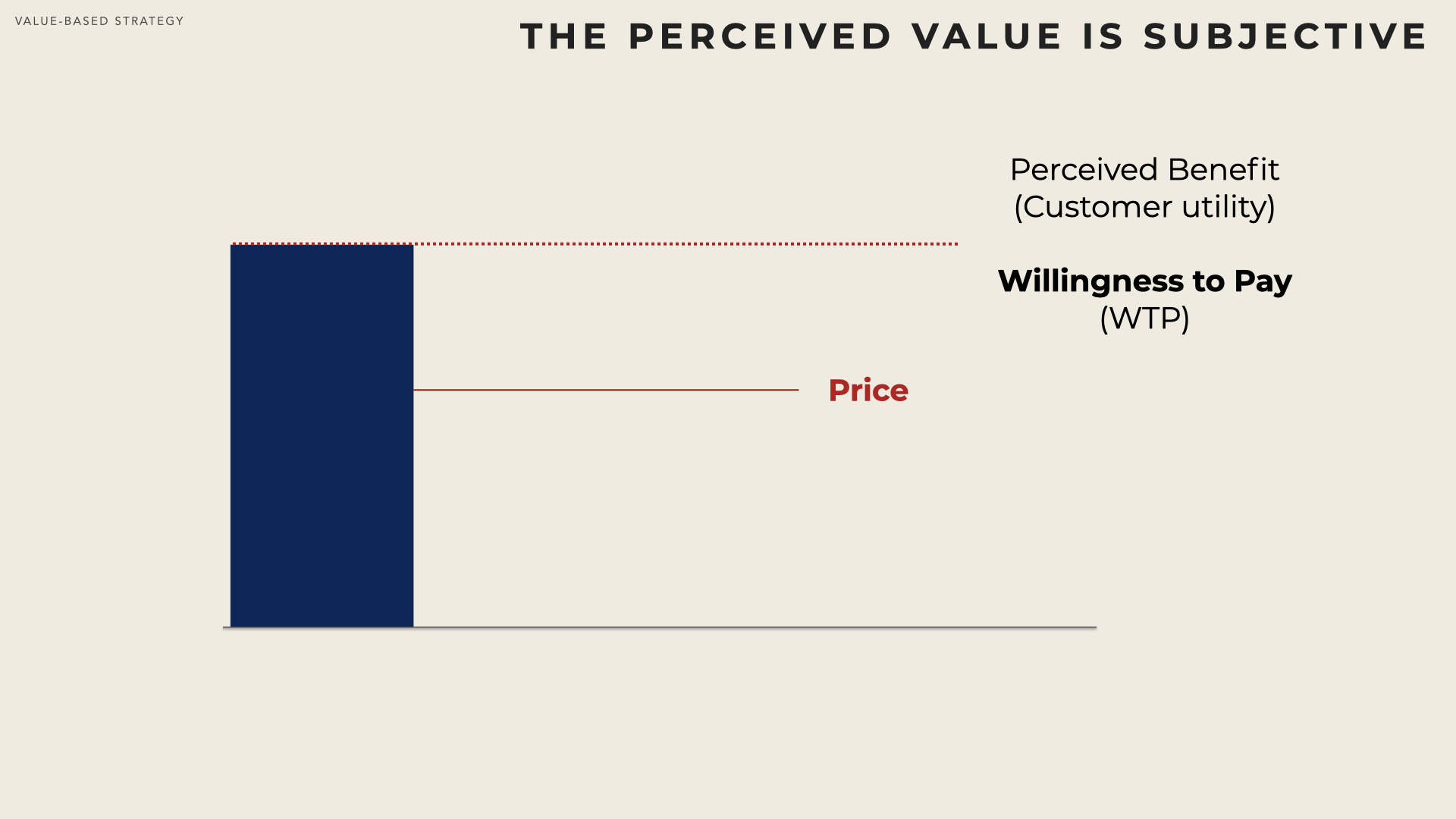

The Willingness-to-Pay is the maximum price a customer is ready to pay to acquire a given good. It corresponds to what economists name usefulness, economic satisfaction.

WTP is the amount for which the customer is (theoretically) indifferent between keeping her/his money or obtaining the good. At a higher price, the customer would rather keep the money (which is worth more than the good’s utility for that customer). If offered at a price which is strictly inferior to the willingness to pay, then the customer can consider a commercial transaction.

Usually, Willingness to Pay cannot be easily measured. Brandburger & Harborne ( [Brandbuger96b] ) suggest the following thought experience to better capture the concept:

if a rational customer is offered a product for free, she should be better off with that product than without it (economists call that the non-satiation axiom).

from that situation, start to take money away from the customer (i.e. ask him to pay). When the amount of money taken away is small, the customer should still prefer the situation with the product compared to the situation without the product.

however as more money is taken away, there should be a moment when the customer prefers to keep her money and give the product back.

willingness to pay corresponds to the amount of money where the customer gauges that the situation with the product (less money) and without the product (with money) are equivalent.

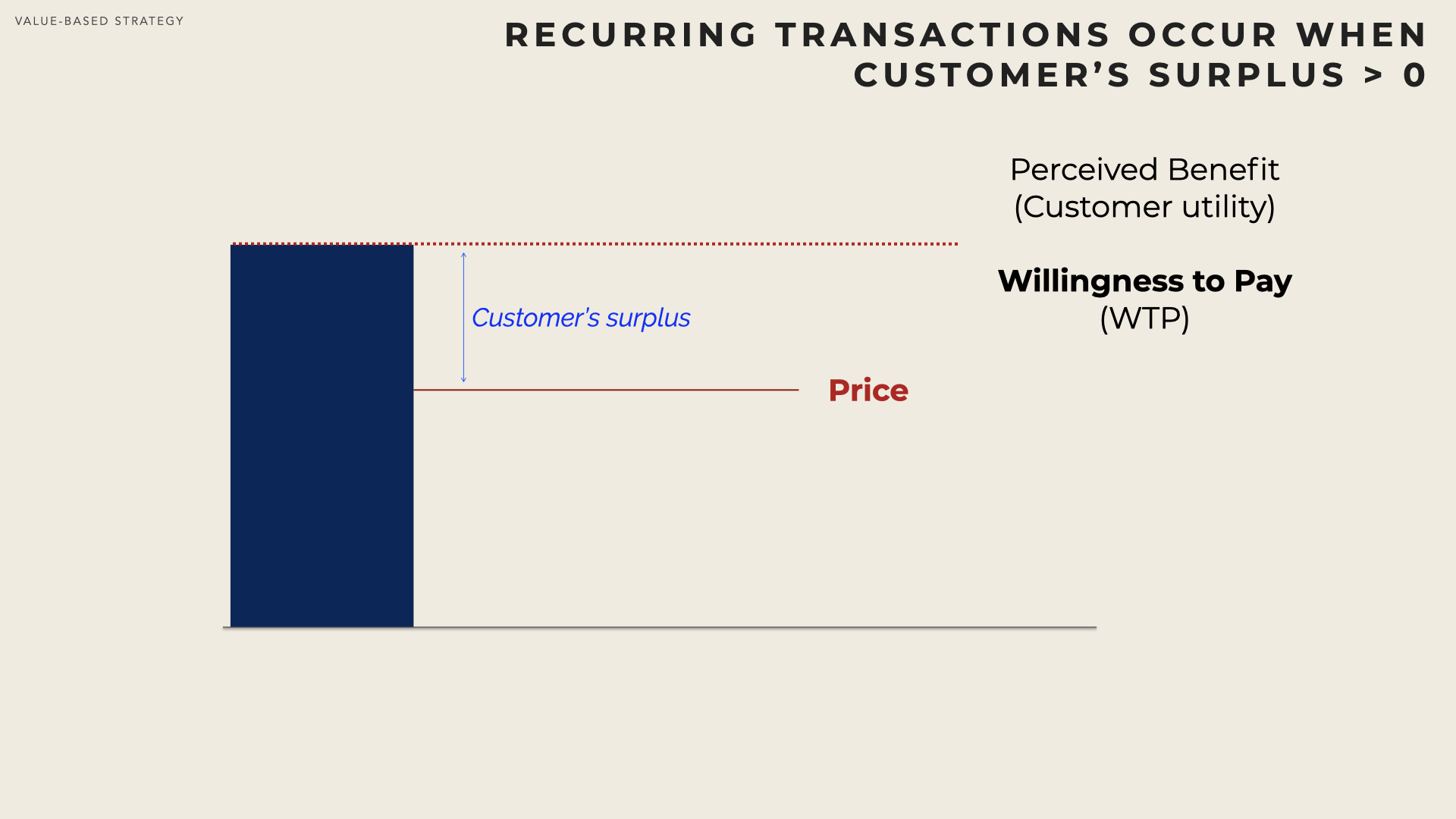

The difference between the transaction price and the perceived value is named customer’s surplus. It is the value delivered to customers by the firm.

Rational customers only transact so that they receive a positive surplus.

This notion is closed to the concept of utility defined in economy, where utility doesn’t convey any ethical, moral, religious or political connotation but only reflects preferences from economic agents. V. Pareto proposed to use the word ophelimity instead of utility. Likewise Irving Fisher suggested wantability, however utility was already too well established in economics literature.

The actual price at which a product is sold results from the bargaining between the customer and the firm (or from market forces).

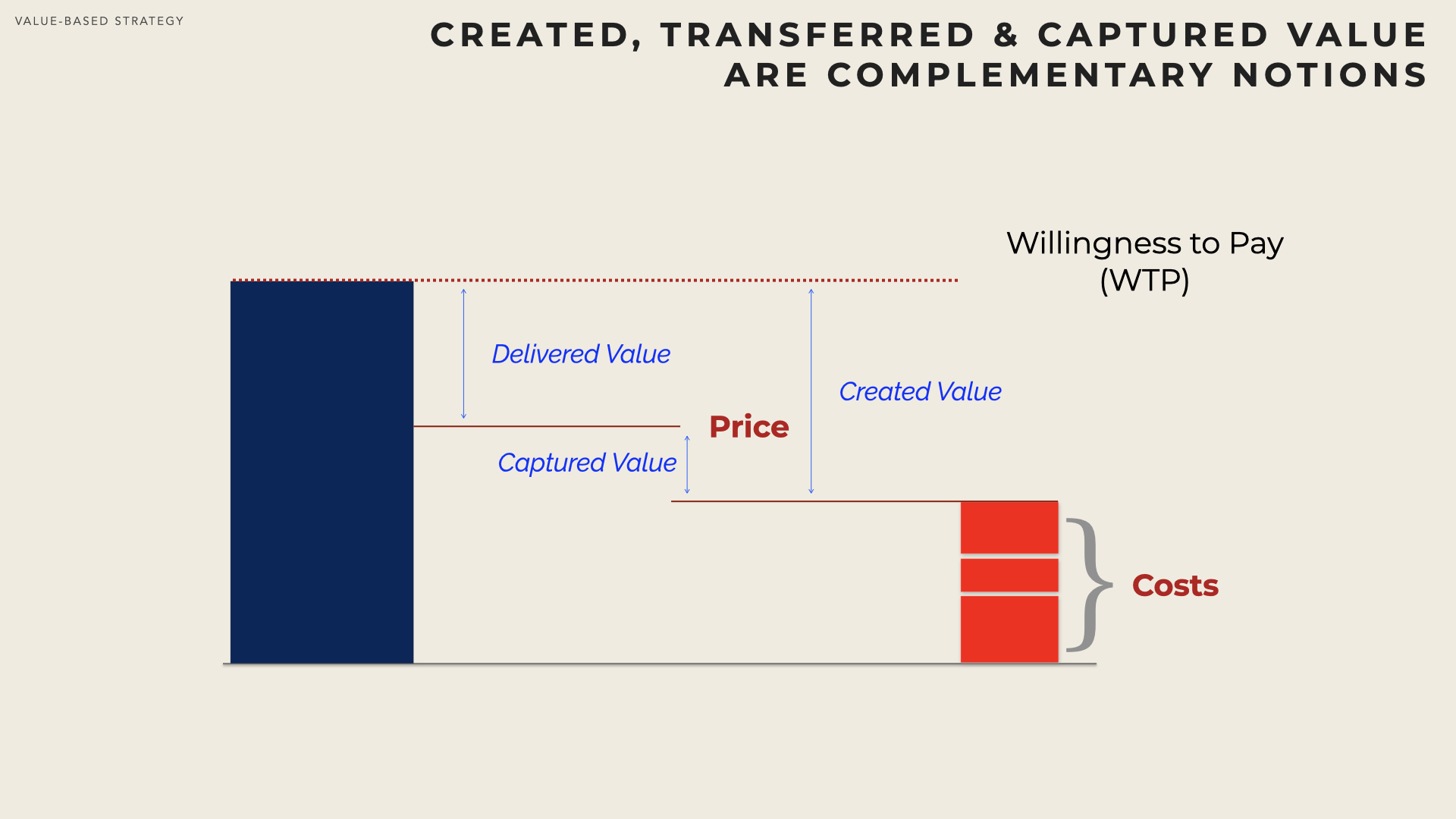

Some of the value created by a firm, is transferred to customers (Customer’s surplus) and some (the difference between the transaction price and the total cost of the good) is kept by the firm. Any firm must ensure that it both creates value at least for some customer groups and claims value so that it can generates some profit.

Value attributes

Human needs are infinite and insatiable. Psychologists define a need as a gap that triggers some action. Several classification of human needs have been established (e.g. Maslow’s pyramid which identifies the need for security, membership, self-esteem, …).

For Customers, Value yields from the perceived ability of a good or service to satisfy a need, that can be practical, demonstrative or any combination of the two.

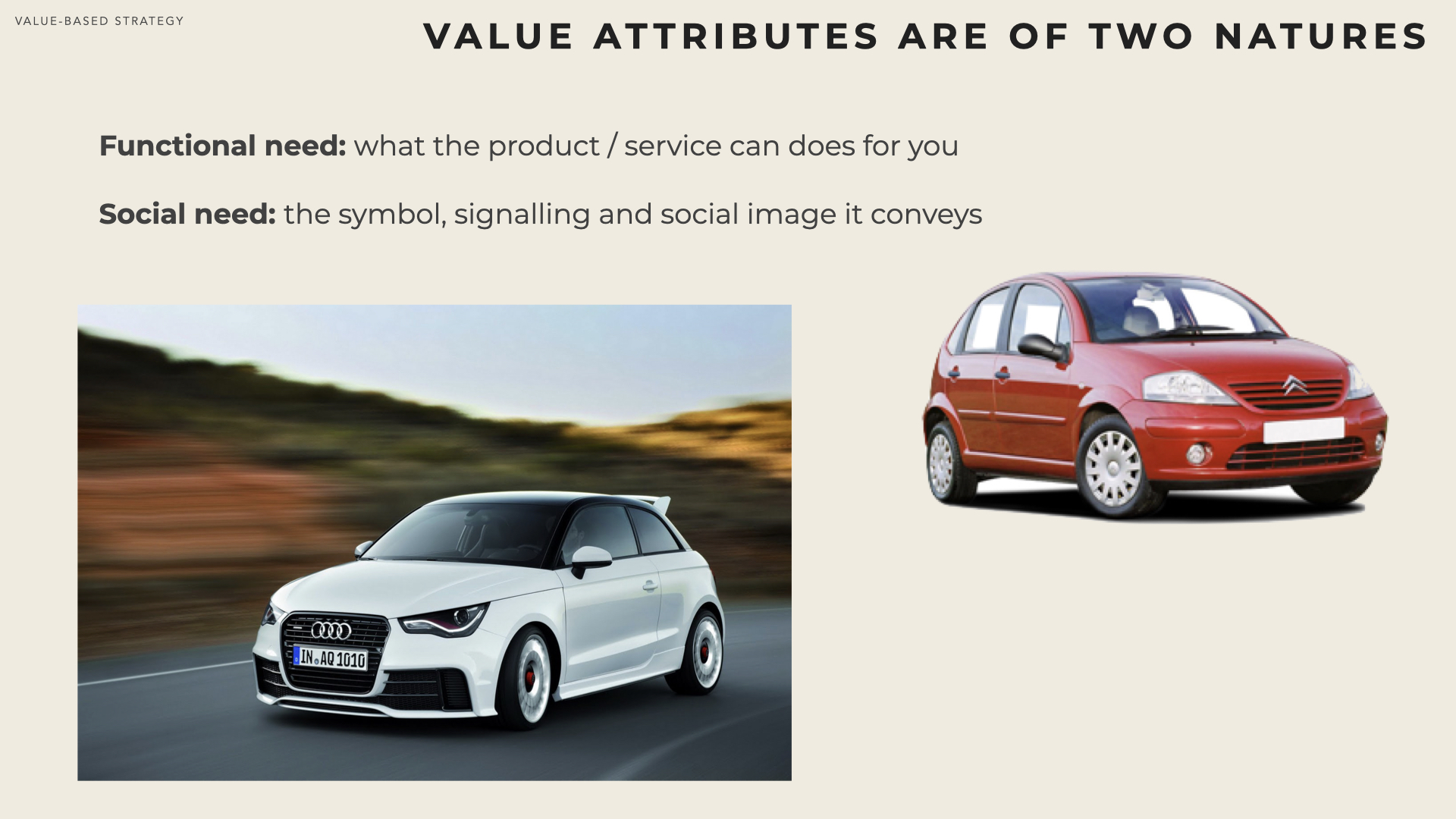

By and large there are only two fundamental types of needs:

functional needs (including basic needs: breathing, feeding, breeding)

social needs (which may be contradictory: resemble others, assimilate to the group but at the same type differentiate oneself from the crowd, be recognized as individuals).

A product or service always aims at satisfying a need. However most needs combine basic needs (functional need) with social needs and are met by socially significant forms (to have dinner at a fancy restaurant vs. eating).

Value can for instance be attributed - see ( [Aurier] ) for a more detailed ontology - to the functional aspects (performance in terms of tangible, concrete rendered service), knowledge acquisition (education, cultural products, museum), emotional stimulation (entertainment, personal experience), self expression and establishment of a social bond.

More often than not, products encompass several attribute, (including several functional attributes).

The value of a proposition must always be considered from the perspective of the customer(s). Value derives from utilitarian aspects but also from more peripheral elements related to the context of consumption, use and/or purchase which represent more subjective but nevertheless real and often substantive sources of satisfaction.

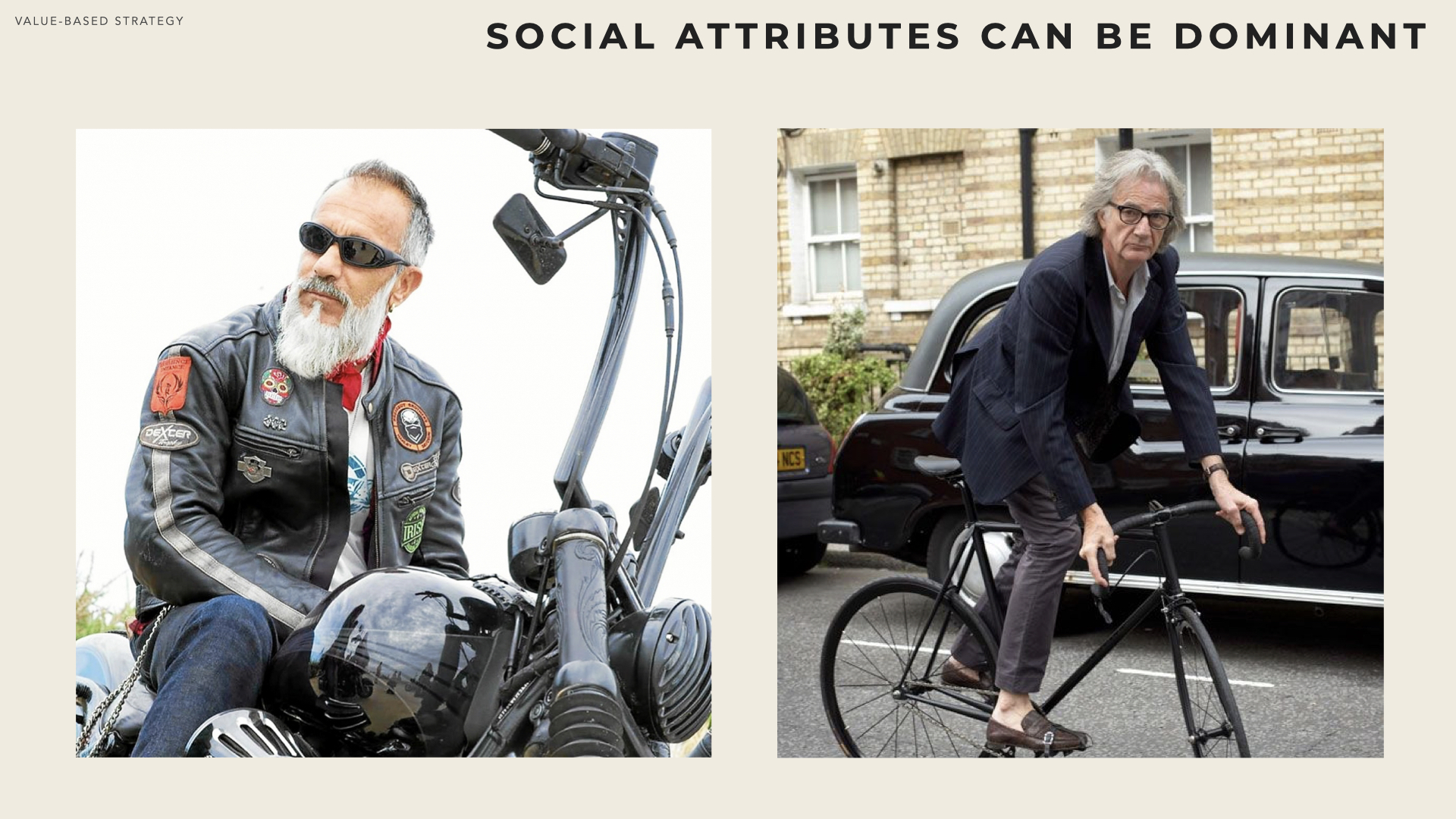

Products & services therefore always encompass, to some extend, consuming signs (willingness to display a status, need for control, need for security). A value proposition has therefore two dimensions: a practical / functional dimension and a demonstrative / social dimension (which is sometimes pre-dominant).

Consumption Context can also Matter

Value Proposition attributes are not limited to the functional & social aspects of the product or the service. Indeed, sometimes the context in which the product/service is consumed also significantly matters.

Dawar ( [Dawar03] ) stresses that on a hot day, consumers are ready to pay 7-fold more for a cold soda. The perceived value of the product is therefore influenced by the circumstances.

Dawar goes on step further an claims that the way the product is channeled to customers (the place in mix-marketing terms) can also seriously affect the perceived value.

Customers don’t always know in advance what they (might) value

While Marketing has grown the concept of focus groups (where people are asked about their perceptions, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes towards a product, or service) many innovators considers that consumers are not always capable of anticipating their needs.

You can’t usually directly access a customer’s Willingness To Pay - and it must therefore be appraised indirectly.

Shareholder value

The term Shareholder Value (paying dividends and raising the stock price) became popular in the 80’s when big companies put increasing their shareholders’ wealth at the forefront of their business goals, to attract new investors and capital.

Shareholder value is the value delivered to the equity owners of a corporation due to management’s ability to increase sales, earnings, and free cash flow, which leads to an increase in dividends and capital gains for the shareholders. Investopedia

According to Paul Barnett, it is Milton Friedman (one of the most influential economist, from the Chicago School, who received the Nobel Prize in Economic Science in 1976) who imposed maximising shareholder value as the sole purpose of a firm. This is now being challenged by academics, practitioners and society at large.

What is Profit ?

Some general managers tend to believe that maximising revenue growth and maximising profit would be the holy grail of management. However, they are making a major flaw in ignoring the level of investment that was required to obtain that profit.

A firm must create value and capture some. More precisely it must capture value in excess of the opportunity costs of its financing. Generating profit is not good enough. Profit must be considered in comparison to the level of capital (equity and debts) it requires to get generated. Profit must be compared to the level of investment that was required. This section explores various ratios used to evaluate the return.

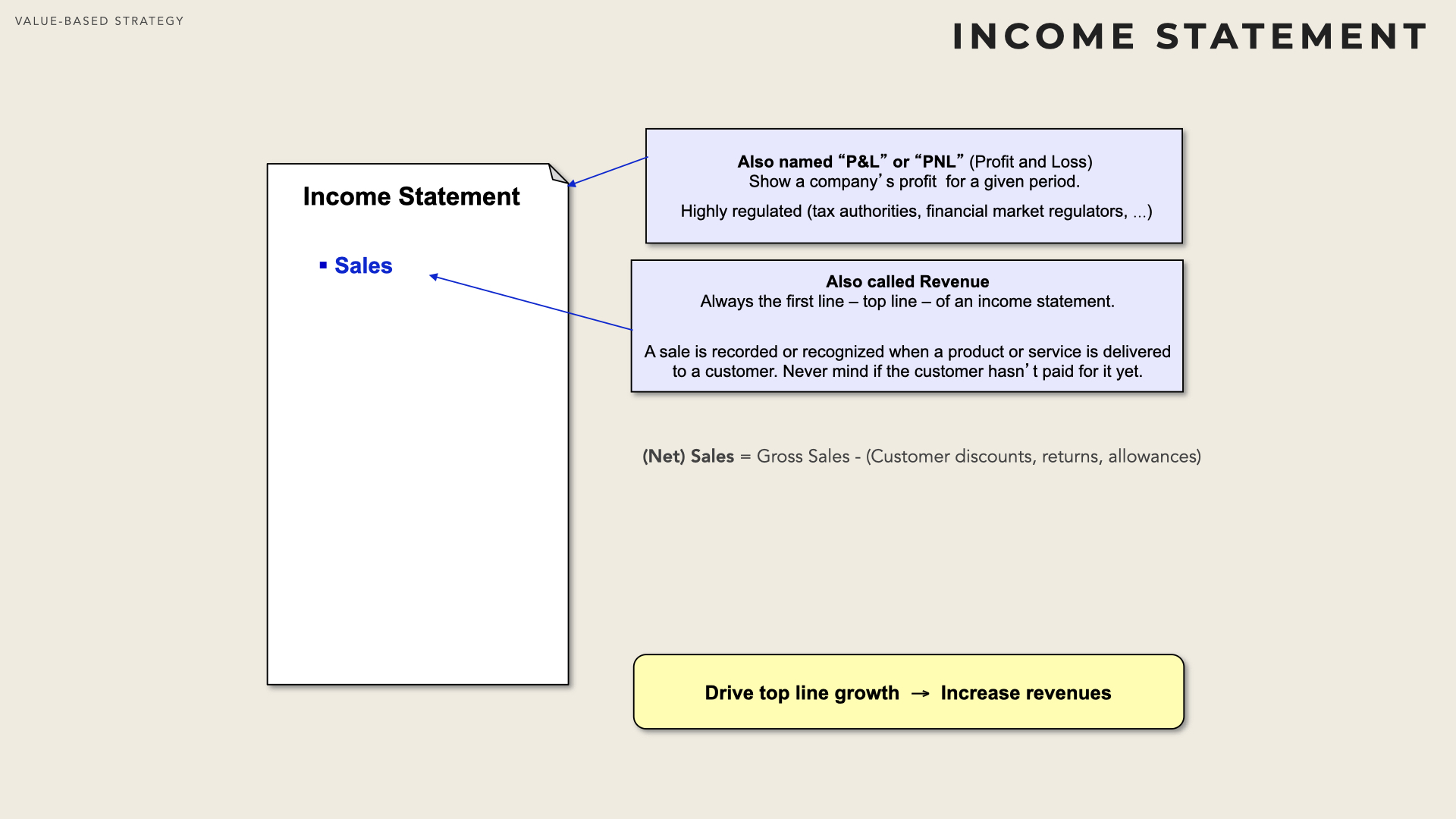

Income Statement

The income statement (also called the Profit and Lost or P&L statement) reports revenues and expenses for a fiscal period.

The Income Statement represents flows that is the summary of what happened during a period (quarter, year).

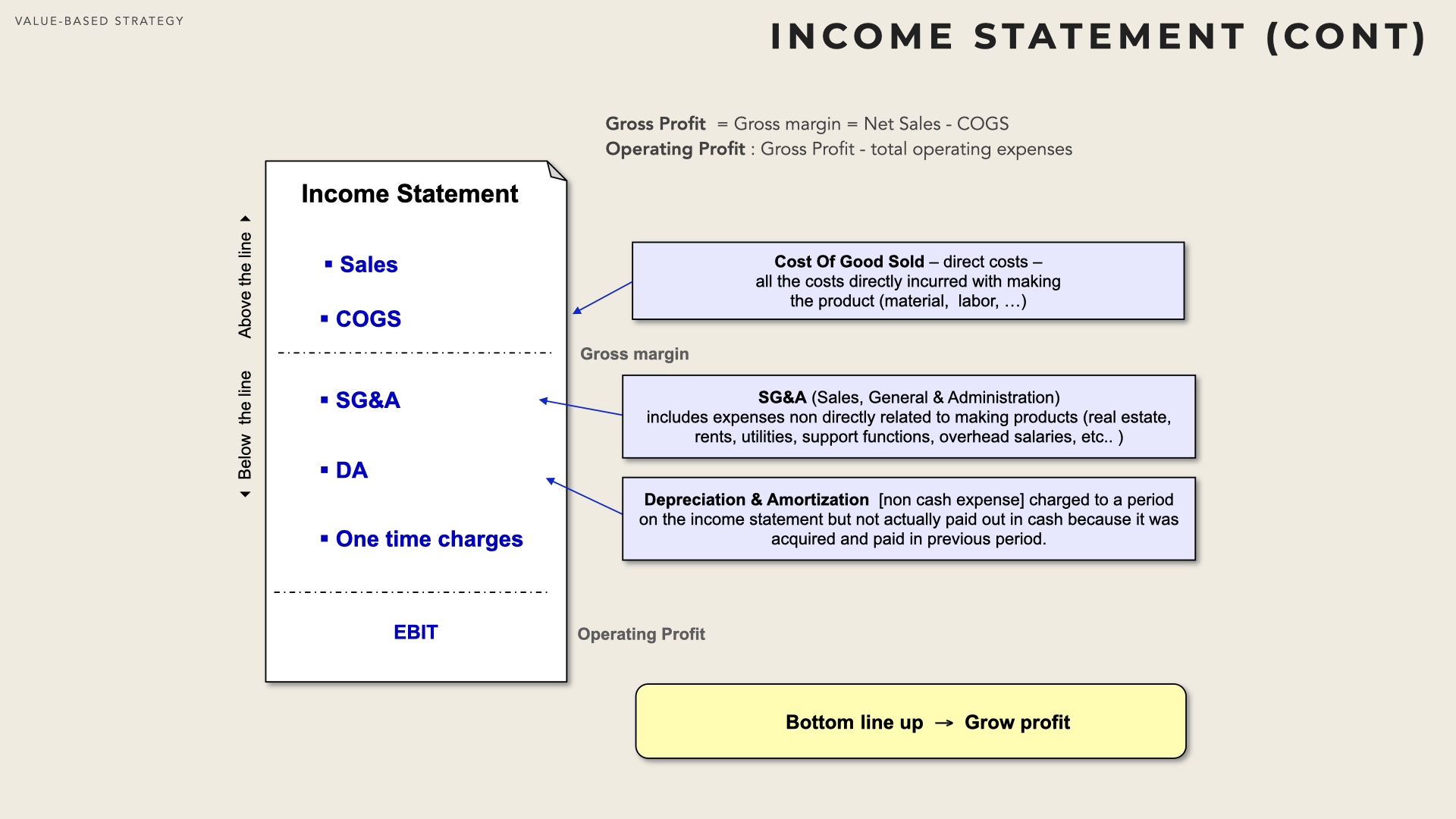

Key indicators can be derived from the P&L:

The Gross Margin is obtained by subtracting ‘cost of good sold’ from ‘revenue’. The Cost of Goods Sold (COGS also called Cost of Sales) corresponds to expenses directly attached to producing the product or delivering the service (e.g. Raw material, direct Wages and salaries, Packaging, Energy & consumables for the machinery, …).

The EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) is obtained by subtracting SG&A (Marketing & Sales, Administration, R&D – sometimes called overhead or non-productive costs)costs and one-off costs (if any) from the gross margin. The EBITDA reflects both direct and indirect costs and is a cash flow item (the sum of cash actually received or spent).

The Operating Profit or EBIT is obtained by subtracting Depreciation and Amortisation from EBITDA. Depreciation and Amortisation refer to the decrease in value of assets that are used during several periods (e.g. plants, buildings, machinery, …). DA doesn’t correspond to any actual payment (payment took place in the past when the asset was acquired). Therefore the EBIT is not a cash item.

For the purpose of preparing an Income Statement, revenues and expenses are not accounted exactly when money transfer occurs: i) Sales are accounted when the product or service is delivered – the actual payment will usually happen later and ii) Expenses are as well accounted when the product is delivered. The P&L doesn’t reflect all the events that altered the financial position (equity increase, bond issue, inventory, etc).

Note: Strictly speaking EBIT and operating profit are two different things in the sense that EBIT may encompass non-operating income as well. However, more often than not, EBIT and opera- ting profit are considered equivalent.

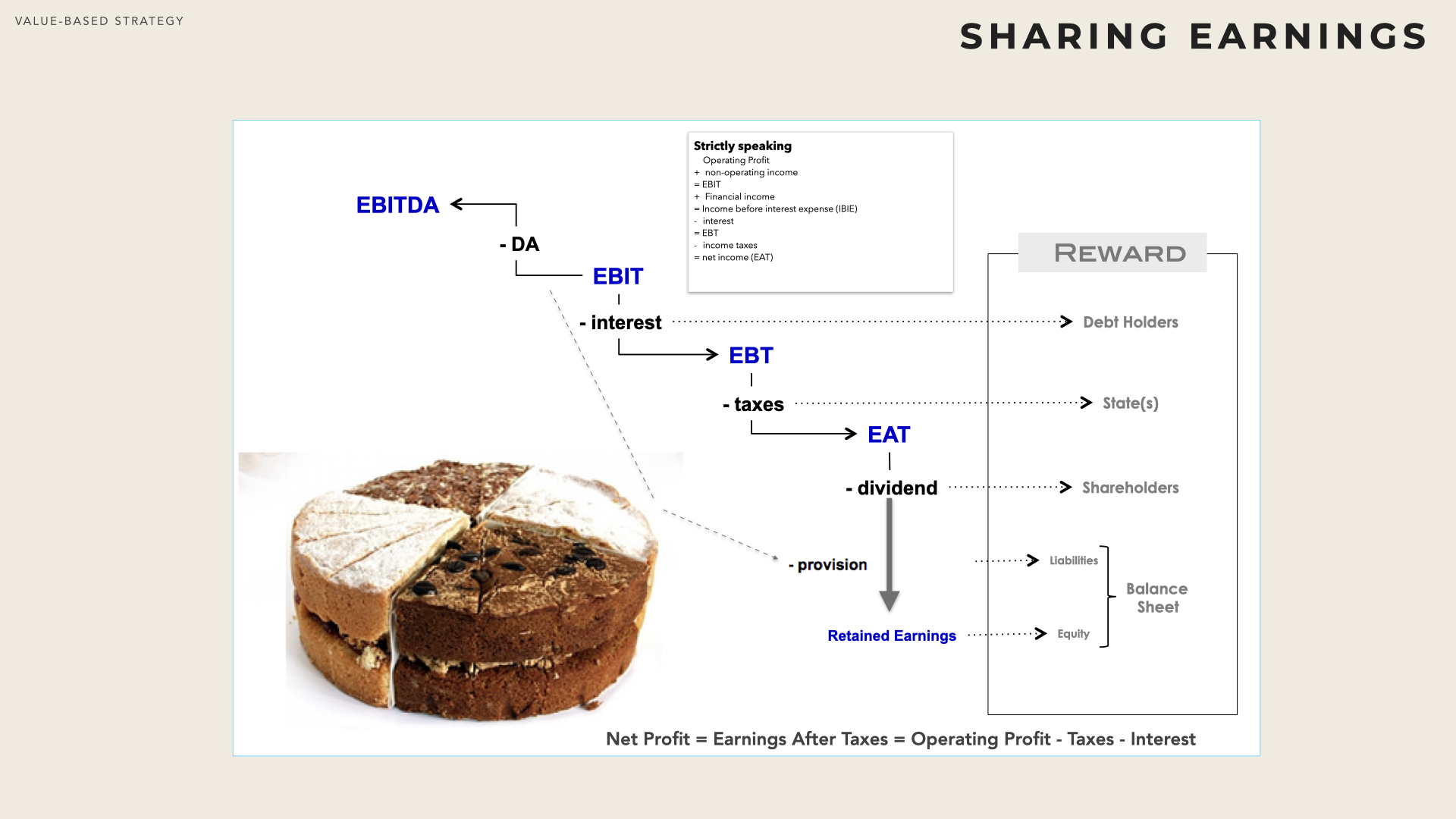

Sharing earnings

The operating profit – which can be seen as the result of operating the business – cannot be kept entirely by the firm. Indeed several stakeholders claim their share of the pie.

What remains (positive or negative number) once interests and taxes have been paid, is named the net income (aka Earnings After Taxes). A part can be paid to the shareholders as dividend and the remaining (retained earnings) is kept by the company (adds up to the equity part in the balance sheet).

Cost of Capital

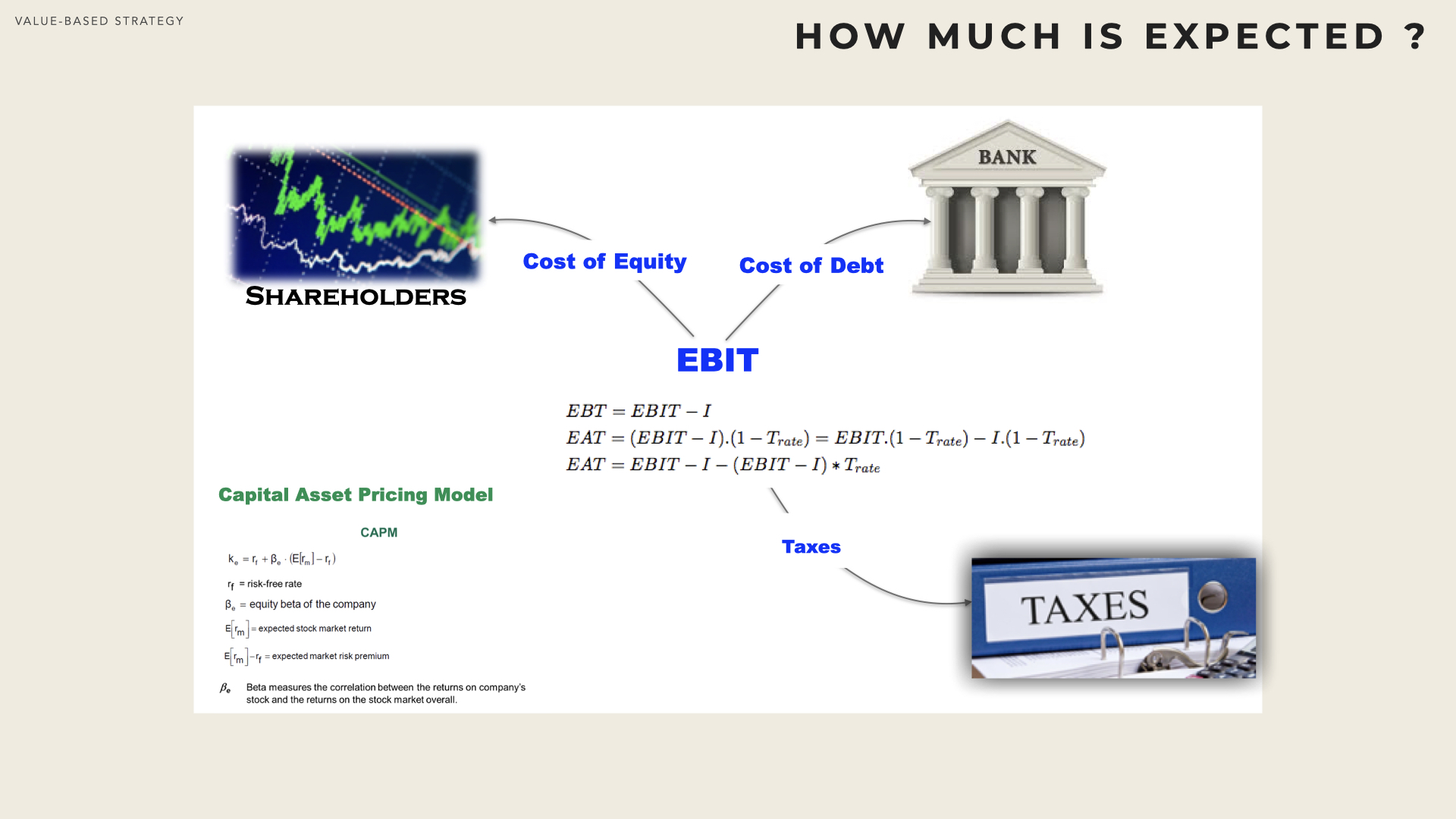

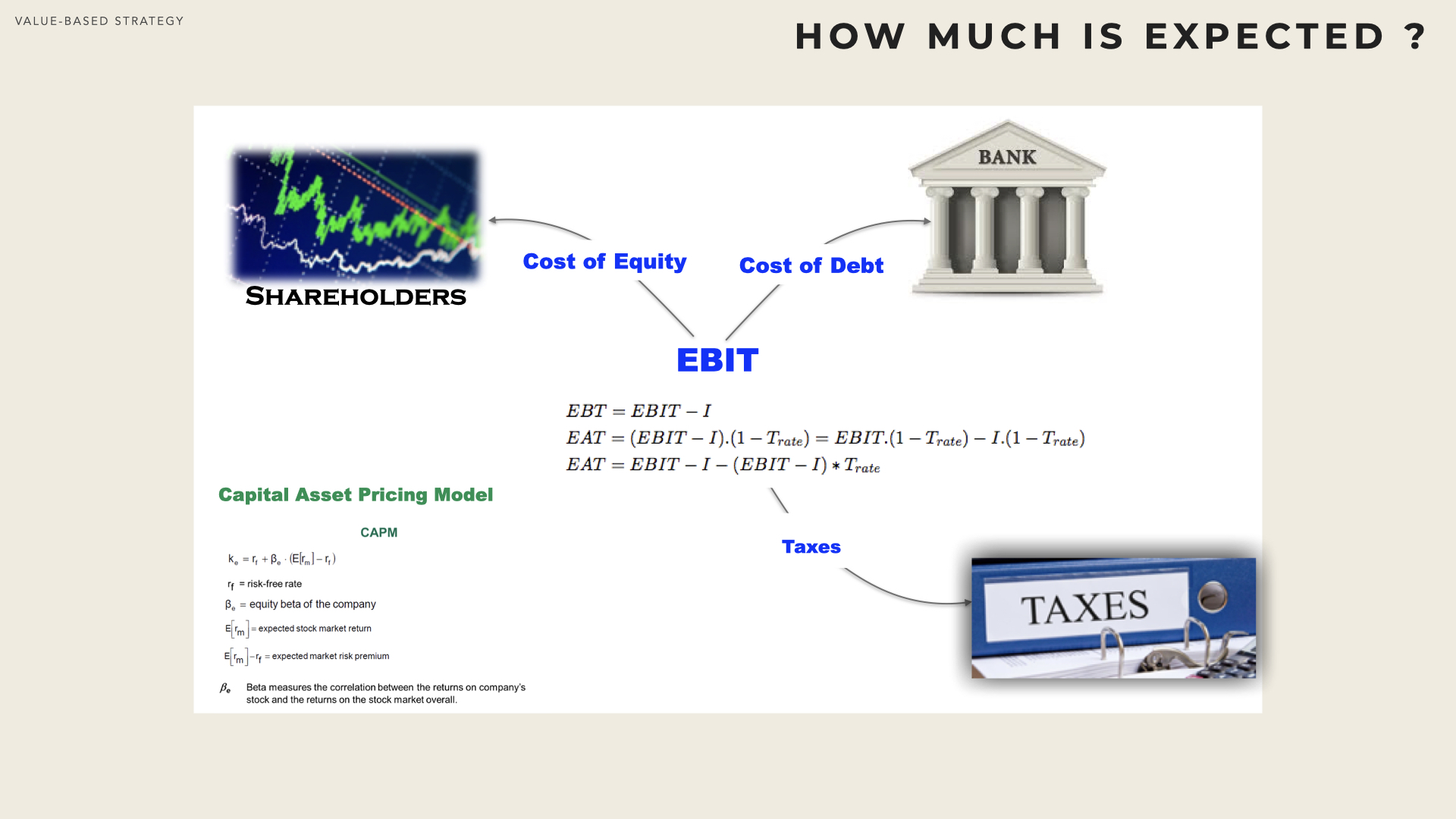

The various stakeholders form expectations about the return they might receive from the firm.

Taxes

Tax authorities are relatively clear about what they expect. The word ’clear’ is arguably not suitable here as tax laws can be very complex and obscure. However taxes are due and are rather deterministic. Taxes are usually computed from the EBIT (i.e. there are no taxes on operating losses).

Debts

In exchange for the money that they lend, debt holders expect to receive compensation (typically an interest rate). From the perspective of the firm this is called the cost of debt.

Shareholders

Shareholders also expect a return from their investment. However (and unlike tax authorities and debt holders) shareholders bear more risks and are associated to the fate of the business.

The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) is one of the most famous theoretical model that assess the appropriate rate of return of an asset. By and large it considers that the expected return for any business should be the risk-free return (typically treasury bond) to which a premium is added, subject to the level of risk of the business.

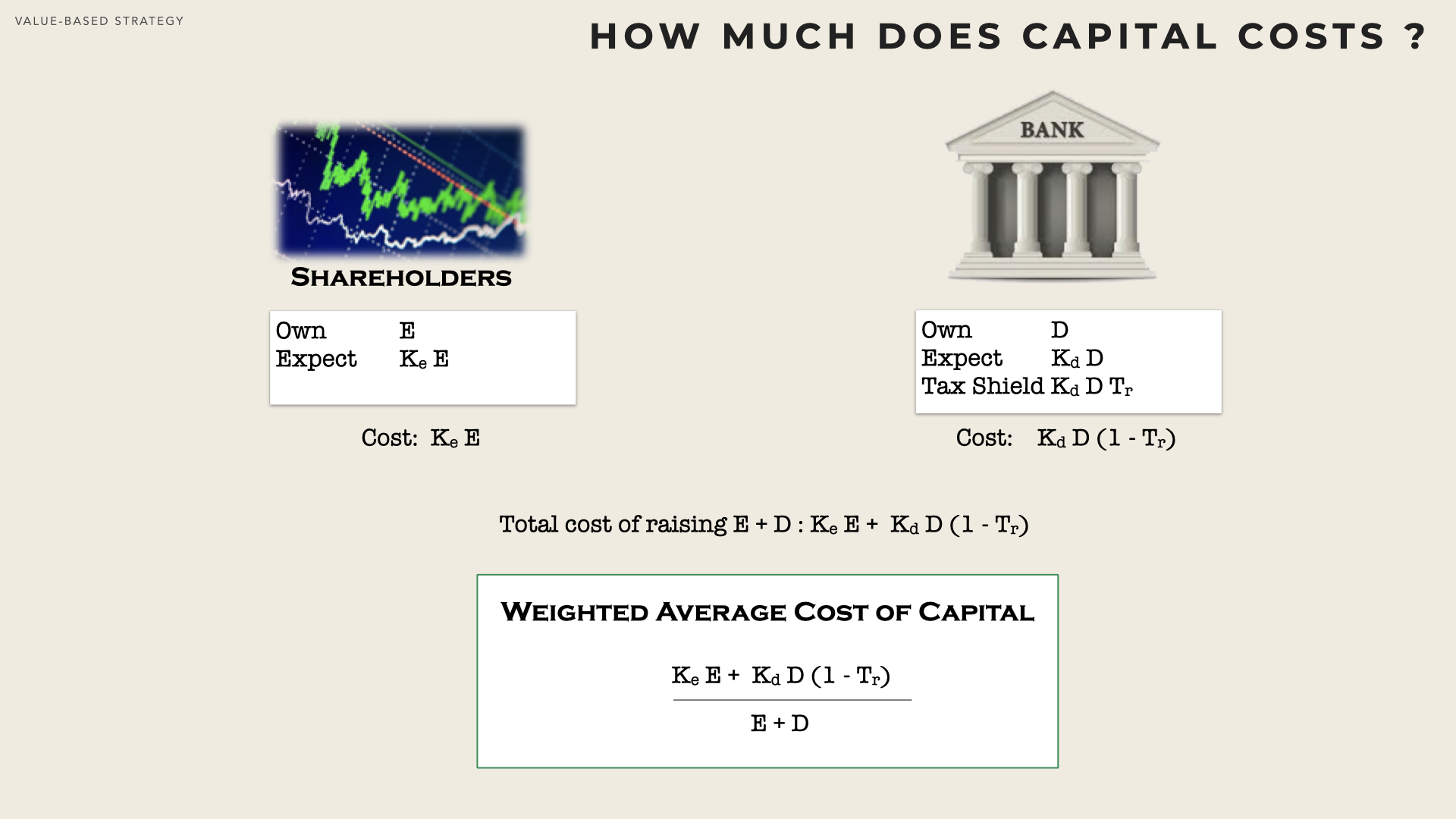

Weighted Average Cost of Capital - WACC

Excluding current liabilities, a firm receives its capital from its shareholders who own the equity (E) and debt holders who own Long-term debts (D).

Shareholders expect \( K_e \) in return for their investment, which for the firm, corresponds to a total cost of equity of \( Ke.E \). Likewise, debt holders expect \( K_d \), which for the firm, corresponds to a total cost of debt of \( Kd.D \). The total cost of raising \( E + D \) is therefore \( Ke.E + Kd.D \). The average cost, named the WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital), of raising one unit (i.e. one euro, one dollar, etc…) is therefore: \( \frac{Ke.E+Kd.D}{E+D} \)