Value Proposition

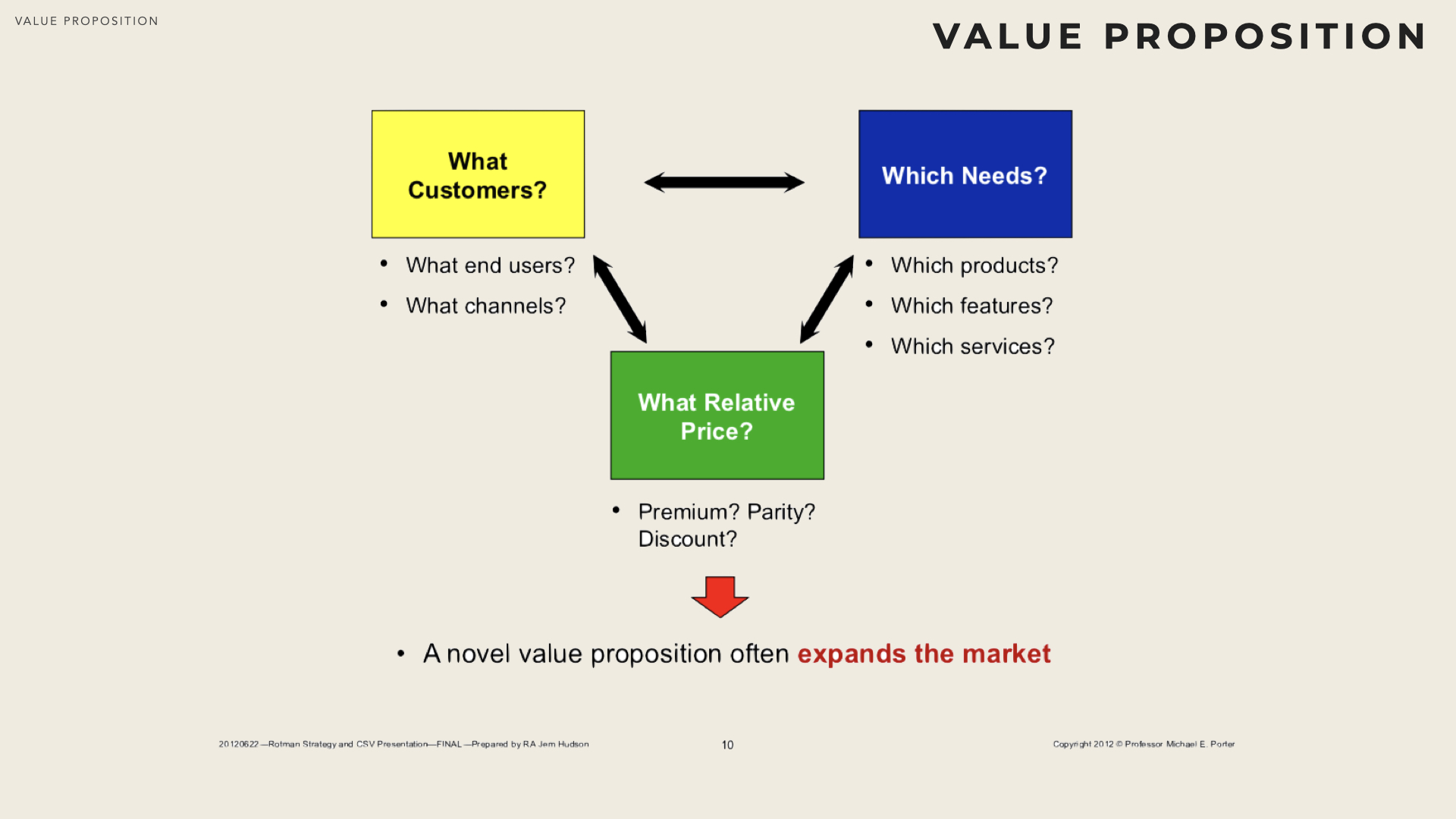

A Value proposition is the description of the offer (product or service) made by a company to its customer and why the offer is attractive to customers.

One of the central questions in Strategy is: which value proposition should be developed? to serve which customer segments?

Value Propositions compete with a broad set of substitutes. Customers, through their behaviours and consumption logic, determine which companies are actually competing.

Hence it is crucial not to start any strategic analysis with an a priori definition of strategic groups. By contrast, it is key to look at actual trade-offs made by customers and understand how their choices depends on the emotional value and usefulness they perceive in products.

Firms compete with each other in product markets to the extent that they may attract the same customer and serve similar needs.

Potential substitutes and new entrants are often the highest competitive threats but also the most challenging to foresee. They are usually the ones who cause the break in the sector and can profoundly change established rules of the game.

As stressed by Peteraf and Bergen ( [Peteraf03] ) „The identification of the originality of the offer in terms of value delivered to the customer is at the heart of the definition of a business model specific to a company. The identification of rivals in the satisfaction of the same need of the customer is an essential task for the configuration of an innovative business model.”

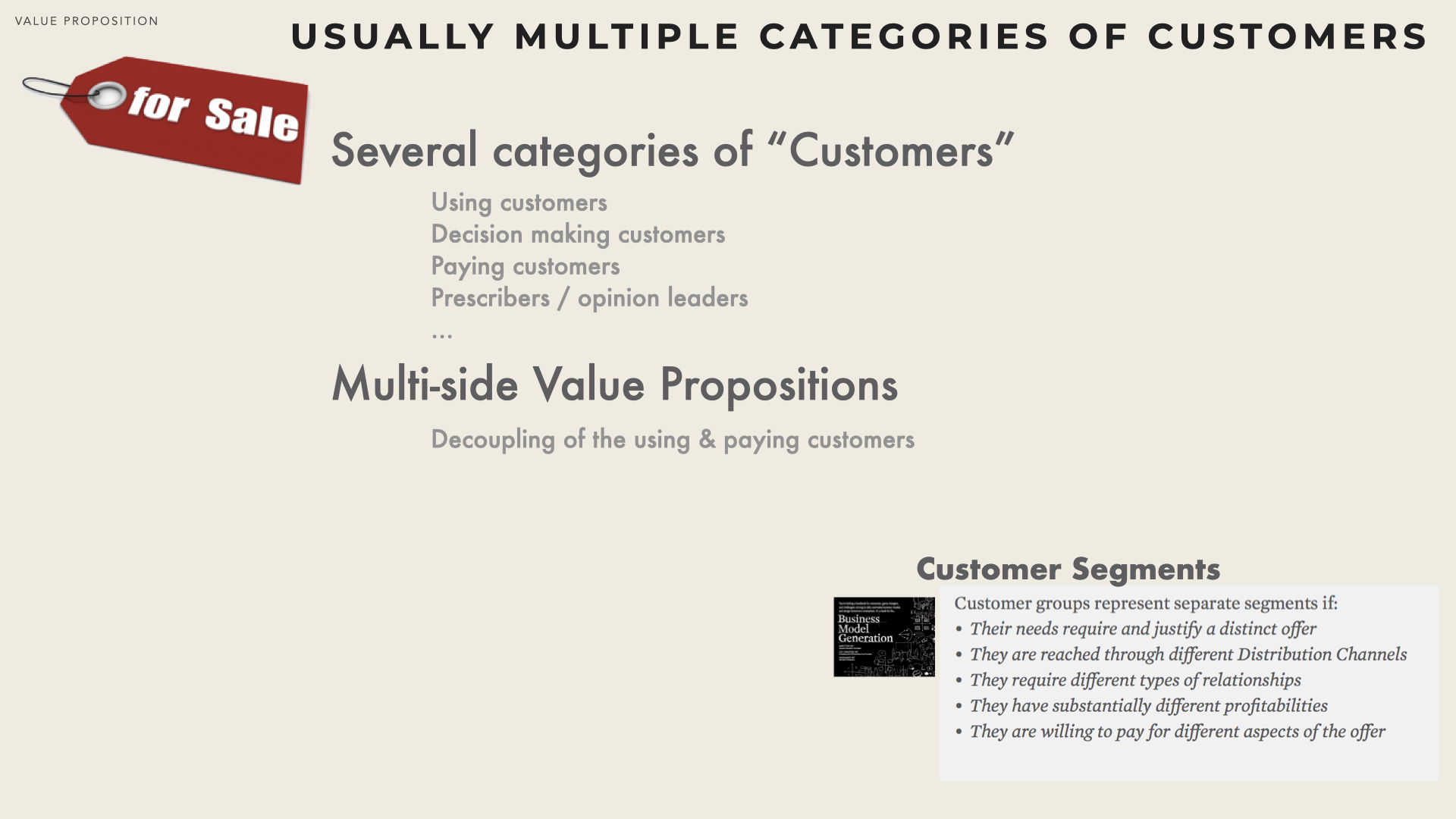

Customers

When dealing with Business Models, the word Customer must be understood in its broadest sense. Theoretically, any stakeholder who interacts with the product or plays a role in the purchase decision, should be considered a Customer.

In their MOOC ( [Lehmann-Ortega15] ) L. Lehmannn-Ortega and Hélène Musikas develop the example of an insulin pen that generates value for patients (who use it) for doctors (who prescribe it), for pharmacists (who sell it) for Care givers (health care staff, family members, who can spend more time with patients and less on technical aspects). The list could be extended as well to Health Care Insurance companies and the Health Care Authorities.

Customer roles will typically include:

Users - or consumers - will gain benefit from actually using the product or service. For instance in the Air Transport system, passengers are usually the users of aircraft (although pilots, cabin crew and mechanics would as well be a different kind of users).

Recommenders - can advise or suggest specific products or services. For some products (e.g. medical treatment prescription) recommenders can select the product for users.

Opinion leaders - don’t necessarily interact directly with users or decision-makers, but their opinion can significantly influence the decision to buy or not to buy. With the advent of the social web, any potential user can as well become an opinion leader / influencer for other customers.

Buyers - paying customers will handle the economic transaction and will usually pay for the product or service.

Decision-Makers - select the product or service. For B2C (Business to Consumers) businesses, the Decision Maker is often also the Buyer and the User. This is usually not the case for B2B (Business to Business) businesses.

„In the past 50 years, the average business model lifespan has fallen from about 15 years to less than 5. Business model innovation is thus no longer one of many ways to gain a competitive edge, but it is a necessary core capability to respond to – and capitalise on – a changing world.” [BCG]

It is therefore, crucial to clearly identify all the stakeholders (potential customers) and understand their motivations to accept or reject a value proposition.

Many Business Model innovations draw from the decoupling of the various customer roles (i.e. the using customers vs the paying customers).

What Job do you hire the product for ?

Clayton Christensen ( [Christensen07] ) proposes a specific framework to help identify customer expectations and competitive arenas. In the original article and also in many videos available on the Internet, the concept is illustrated with the story of a fast-food restaurant that was seeking to improve the sales of its milkshake sales.

The restaurant had done a lot of data crunching and segmented its market both by product (milkshakes) and by demographics (attributes of milkshake drinkers). They also had run focus groups where they asked to representative customers what they would fancy. Despite all these quantitative and qualitative data gathering, the restaurant hadn’t substantially improved its sales.

The restaurant then enlisted a team of researchers from Clayton Christensen’s lab. They approached the topic by raising the question:

“What job arises in people’s life that causes them to come to this restaurant to hire a milkshake?”.

On the first day they stood in the restaurant for several hours, recording very detailed facts about customers: were they coming alone or in group, what time did they get to the restaurant, did they buy other food, did they eat it in the restaurant or drive off with it, etc. It turned out that half of the milkshakes were sold before 8 am, to people always alone, it was the only thing they bought and they drove off with it immediately.

On the second day the researchers interviewed these specific customers and discovered that they all had a lot and boring drive to work and they had to do something to keep the commuting interesting.

The restaurant was in fact facing two categories of customers and was therefore playing in two distinct competitive arenas. In the morning it was facing commuters and in the afternoon parents with Children. The two categories of customers had very different expectations and were ”hiring milkshakes” for completely different jobs.

We often wrongly assume that we know right away in which industry we compete. However, the competitive arena(s) in which you are competing can only be unveiled by really scrutinising the job the customer is hiring you to do.

Once you have clearly figured out what jobs customers are hiring you to do, you can more easily identify:

which customers and buyers are you targeting ? (i.e. who can benefit from the job your product can do)

who your suppliers should be?

who your competitors are or might be ? (i.e. who else can do identical job)

who might be potential entrants / substitutes? (i.e. who may do similar jobs)

Pricing

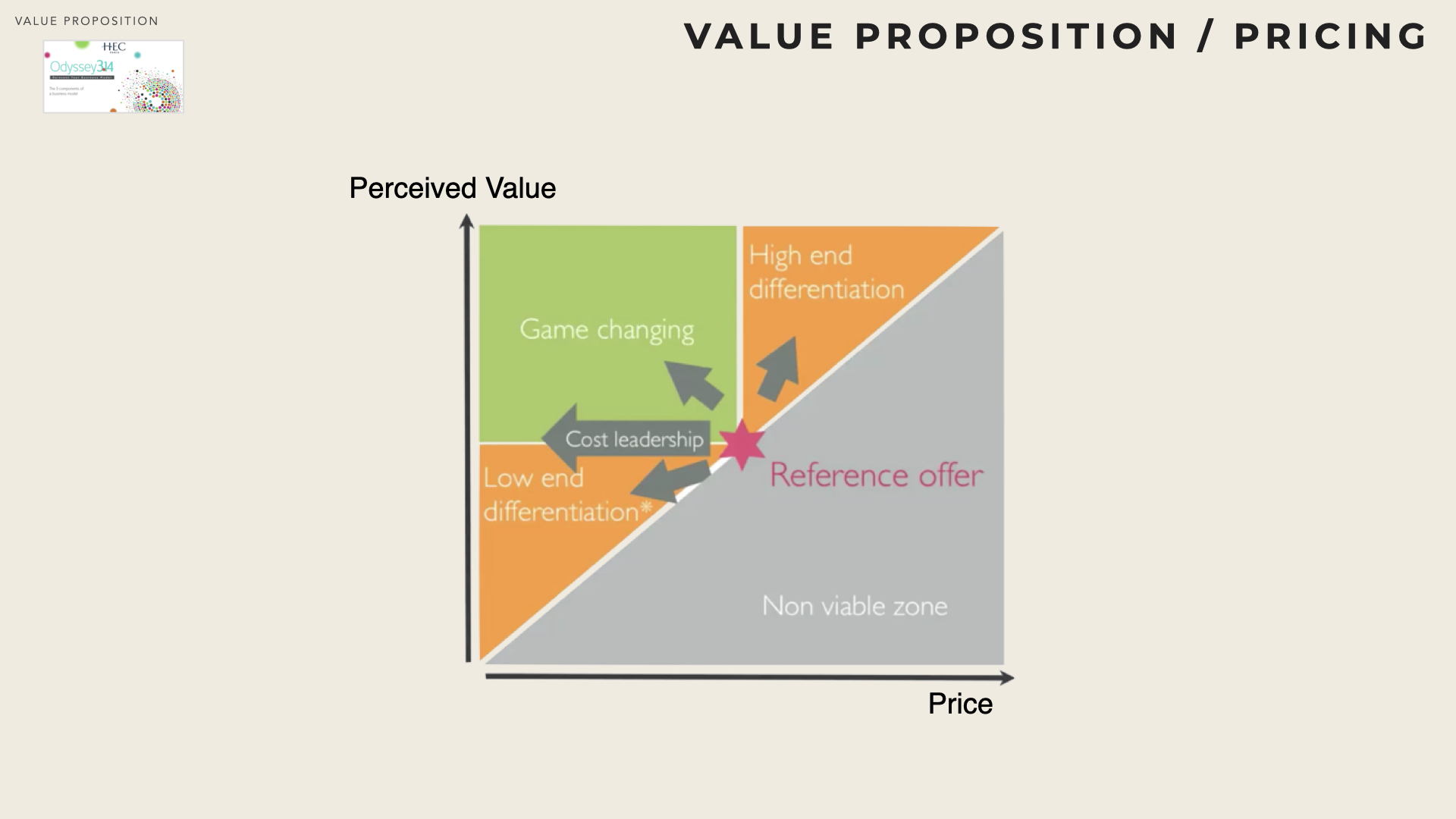

For a given type of needs there might exist many different value propositions. A common way of comparison is to draw them along two axes: customer perceived value and price. While many combinations are possible, five distinct areas can be spotted.

Reference Offer - when a market is mature enough there will be a value proposition (or range of value propositions) that is considered the reference offer both for its price and its (perceived) value. Any other proposition will be compared against this reference point.

In a nascent market, the reference offer is usually the first entrant. In case of market shake-up the reference can be the products that are being substituted. Sometimes, the reference offer only exists in customers’ mind (e.g. as an average offer).Non Viable zone - any value proposition that would yield less value than the reference offer but at a higher price would obviously be disregarded by customers - who would accept to pay more for less? Likewise, at any requested price, any offer that doesn’t bring enough value (relatively to other VPs) is considered as non viable.

Price discount a first differentiating option is to offer similar value (compared to the reference offer) at lower price. This option to be viable for the firm requires that the firm can deliver the same value for less cost, hence the name of Cost Leadership. When several players are capable of delivering this option it usually becomes the new reference offer (and the former reference point becomes non viable).

Low-end differentiation less value is offered at a discount compared to the reference offer. Such value propositions would not appeal to all customers but it can be viable if some customers are ready to trade product attributes against a price discount. Low Cost Carriers in Aviation are typically offering less services at a cheaper price.

High-end differentiation this is the opposite approach. New features are included to the product for a higher price. Building on the same example a first class airline ticket offer more comfort but is significantly more expensive than economic class.

Game Changing is a position that provides both a price discount and value increase (at least for some customer segments). When a game changing value proposition is introduced, it is likely to supplant the existing reference offer and quickly become the new reference point.

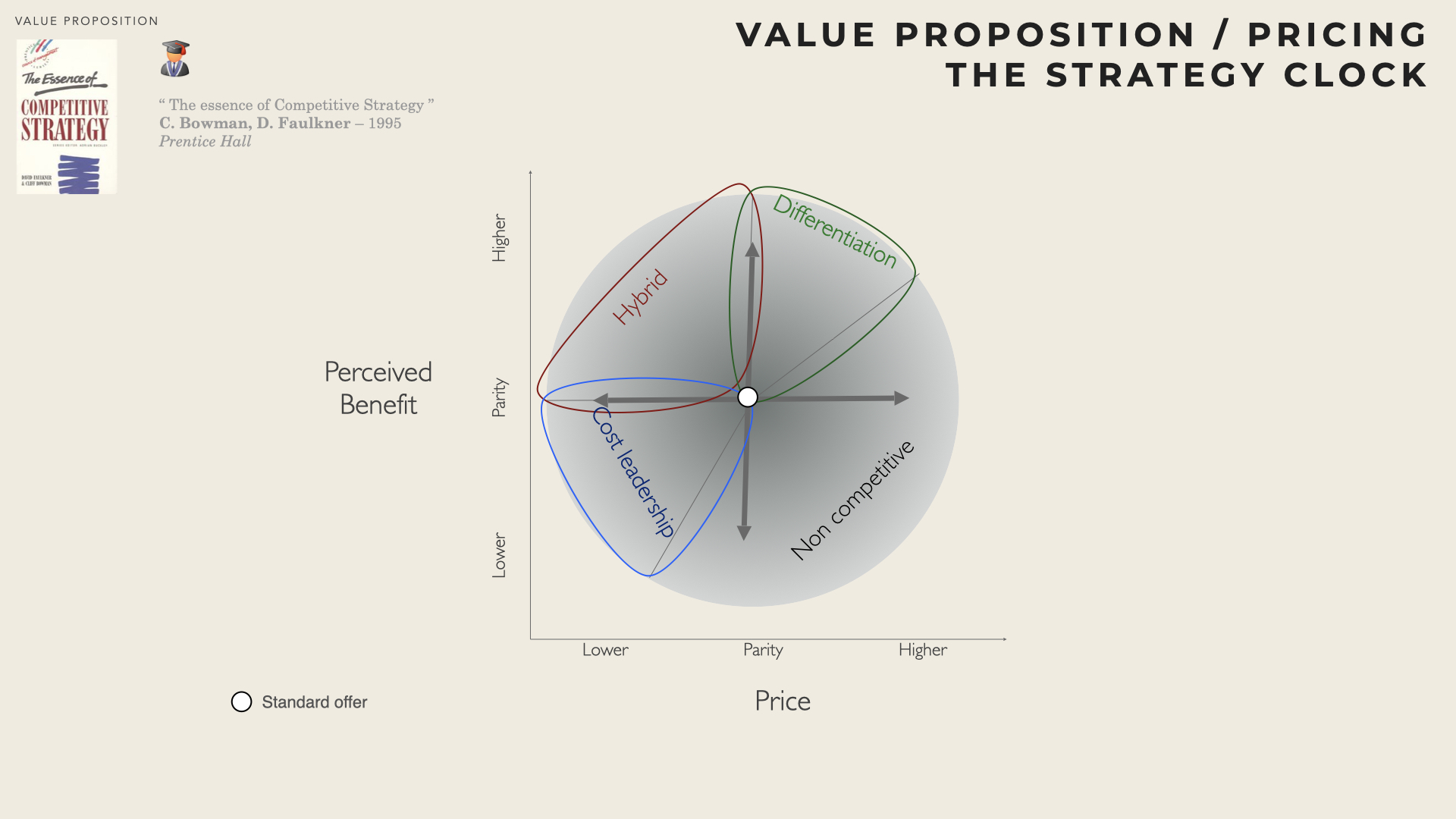

Bowman’s Strategy Clock

The Strategy Clock ( [Bowman97] ) is an other model that explores the various value/price positions.

In its simplest version, it stresses tree areas: i) cost leadership strategies that allows for different combinations of lower price at lower perceived value, ii) differentiation strategies with above average value proposition at a premium, iii) non-competitive strategies that are non-viable and iv) hybrid strategies with both above average features and cheaper price.

It is noteworthy that with this model, differentiation means more value.

At 12 o’clock - Differentiation without any price premium - corresponds to a highly differentiated product/service (highest perceived value) that is offered at parity price. This position can usually not be sustained in the long run (especially not if higher costs are implied) but still can be chosen as a market entry strategy to quickly gain market shares (more features at no extra cost)

At one o’clock - Differentiation with price premium - represents the typical differentiation strategy where a higher perceived value translates into higher prices.

At 2 o’clock - Some differentiation with high premium - this is likely to soon become some sort of focussed differentiation (i.e. targeting a customer segment with specific customer needs / addressing an area with little competition). Although the perceived value by the average customer is close to parity, the specifically targeted segment see far more value (e.g. there is one feature that is of no use for the average customer but key for the targeted customer) and is therefore willing to pay more.

3 o’clock to 6 o’clock non-viable positions

7 o’clock - Low price with lower value - This is the typical no-frills strategy (e.g. low cost airlines) where a company downgrades the product attributes, hence both the perceived value and production costs.

9 o’clock - Low price at product parity - this generic cost leadership strategy combines lower price and reasonable perceived value (compared to the average competitor). In this position a company would drive its costs to the bare minimum and balance very low margins with high volume. A well-installed cost leader can sustain this approach. However there is a risk that prices become unstable and that a price war breaks out, which would i) benefit consumers only, ii) destroy company value and iii) usually lead to industry consolidation

10 - 11 o’clock - Lower price and higher value - This zone allows for major changes: strategies that both involve low price and some differentiation. The perceived value (at least for some product attributes and some customer groups) is above average while price are still below average. A hybrid strategy can be chosen by a company wishing to enter a new market (product segment, export) or to speed-up market penetration and create customer lock-in effect (e.g. proprietary standard). Some companies can sustain hybrid strategies over a long period of time. Furniture store IKEA, for instance, combines economy of scale, no frills (DIY, no delivery, etc) and differentiated design.

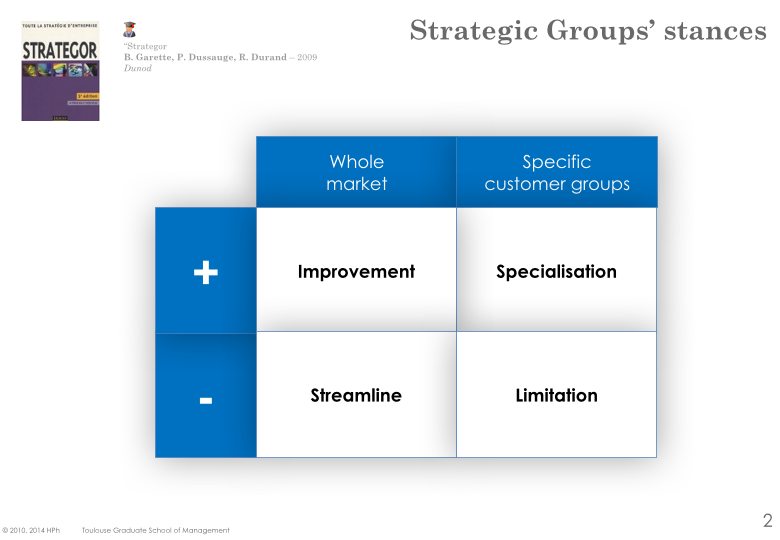

Challenging the reference value proposition

In any market, the value proposition offered by the larger bulk of firms (dominant strategic group) is the reference and other strategic groups need to differentiate from that standard.

Improvement better value proposition for the market as a whole, which shifts the reference value proposition.

Specialisation value proposition specifically targeted to a dedicated market segment (specific needs e.g. extra-large size in the clothing industry).

Streamline offer a simplified product/service at lower costs.

Limitation low cost offer dedicated to a specific market segment.

The issue with the limitation/streamline approaches is one must ensure that i) there is a sufficient creditworthy market and ii) the value proposition is not too far from the reference offer.

Complements

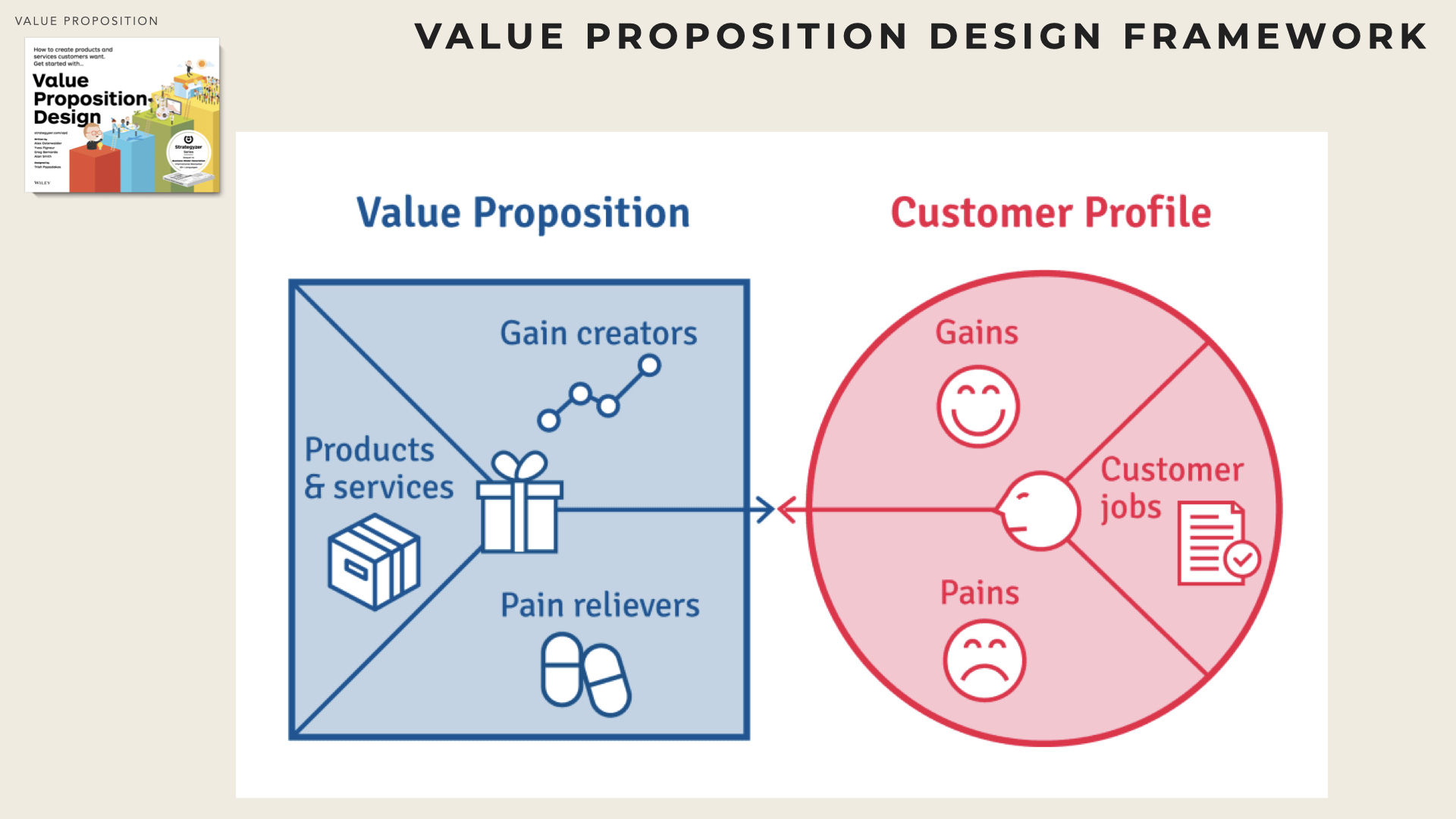

Value Proposition Design Framework

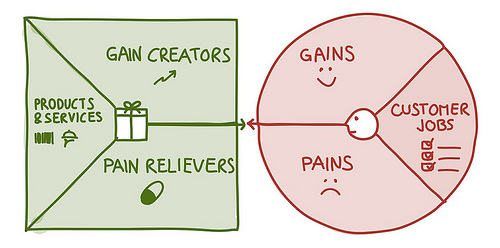

The value proposition design framework ( [Osterwalder12] ) aims at defining in a more structured way the most adequate value proposition.

Please note that this section is deeply inspired from the web site Business Model Alchemist .

Identify customers and the needs they are seeking to satisfy

The first step consists in identifying customers or potential customers.

From there, one should seek to identify what the targeted customers are trying to achieve, what are the problem they are trying to solve (aka customer’s jobs), the needs they are trying to satisfy. It is noteworthy that needs may not be only functional (i.e. complete a specific task) but can also be social (e.g. status, power, belonging) and emotional (e.g. aesthetics, security, …).

Once needs are clarified, one should consider all potential sources of pains (i.e. negative emotions, frustrations, costs, risks, inconvenience, discomfort, under-performance) that are experienced by the customers before, during and after getting their need satisfied.

Likewise, one should identify all the features and benefits that customers expect, desire or would be thrilled by. Again this is not limited to functional aspects but may cover as well social gains, positive emotions, cost-time-effort savings. Existing products and solutions are likely to already address some aspects (but probably not all or not for all customers).

Design a Value proposition

The value proposition is the response to a customer need. It may encompass product and services (tangible good, one-to-one customer facing service, on-line interaction, branding and other intangible aspects, financing services, etc).

Once the pains are clearly identified, it is easier to check how the value proposition alleviate these pains and how much pains are eliminated. Likewise, it is easy to underline which customer expectations are addressed by the value proposition and what specific benefit (possibly compared to what competitors do) is brought.

C. Christensen ( [Christensen08] ) stresses four aspects that should be considered in priority to unveil untapped market spaces:

Wealth barriers sometimes customers don’t have enough revenues to afford existing value propositions. When Tata looked at creating a new car for Indian domestic market, they knew they had to compete with US$ 2500 scooters. The size of the Indian market allows for rebalancing the profit equation through volume.

Skill barriers customers don’t always have the knowledge, technical background or competence to use mainstream solutions. This is particularly true in Business to Business segments where the solutions targeted at SMEs are different from the solutions used by large corporations.

Time barriers mail-order selling and more recently internet-based shopping have grown as consumers get aware of the time required to shop in physical stores in city centers or shopping malls.

Access barriers some form of asymmetry of information may make the service and / or product difficult to find and access. For example, independent consultants are usually barely visible outside their close network. A bypass strategy can consist in relying upon a business ecosystem that is sufficient to leverage the value proposition.

Disruptive innovation

The term disruptive innovation was coined by Clayton Christensen who provided an explanation for the failure of well-respected companies and the appearance of new value propositions / players ( [Christensen97] [Christensen00] [Christensen03] [Christensen04] )

„few academic management theories have had as much influence in the business world as Clayton M. Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation.” ( [King15] )

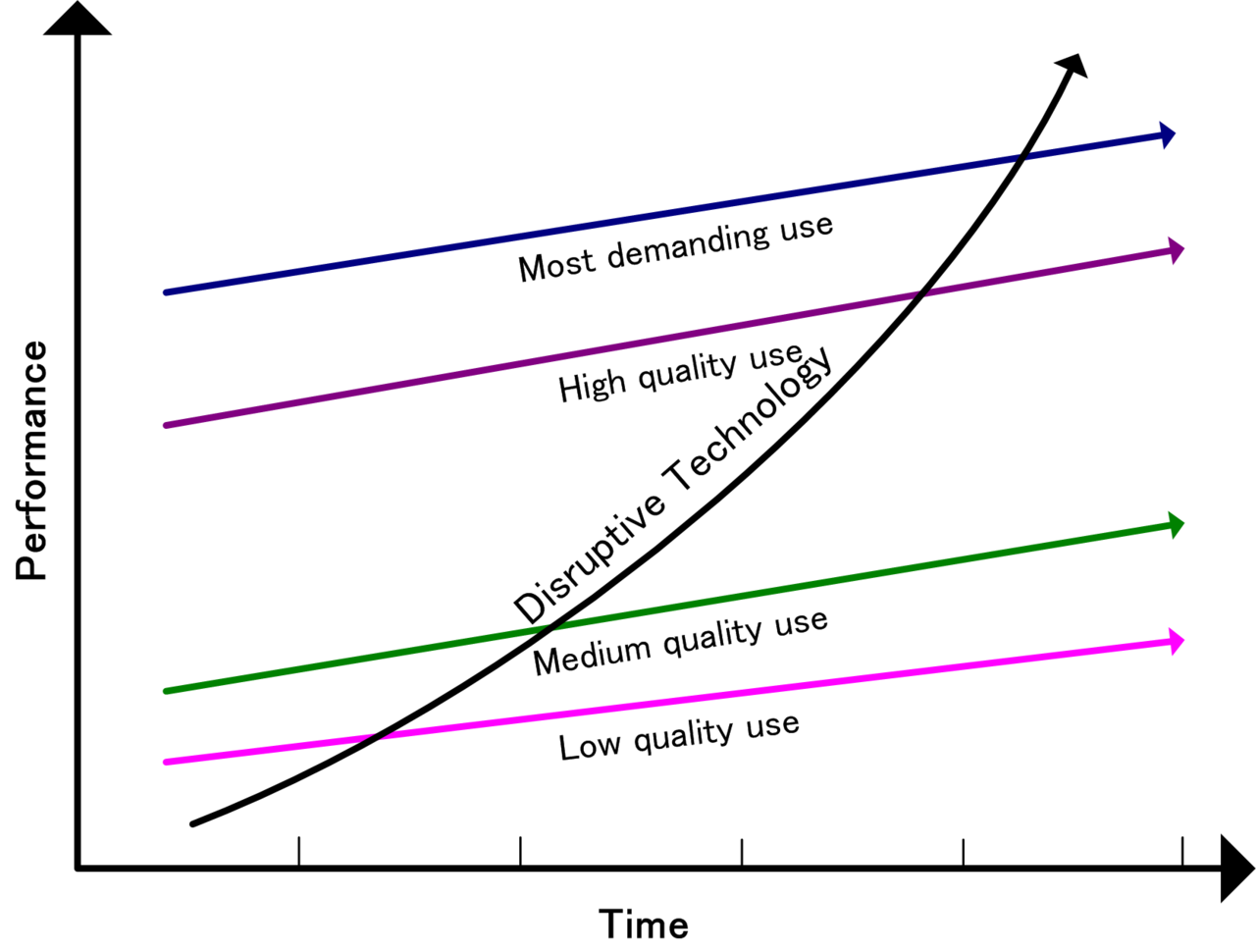

Christensen notes that when a company tries to satisfy its existing customer base, it usually focuses on improving its current product/service offering and will typically add more features or increase performance. More often than not, the value proposition will overshoot customers’ expectation and soon become

„ too sophisticated, too expensive, and too complicated for many customers in their market” [claytonchristensen.com]

Christensen stresses that companies pursue product/service improvement at the higher tiers of their markets because this is what has historically helped them succeed:

„by charging the highest prices to their most demanding and sophisticated customers at the top of the market, companies will achieve the greatest profitability” (Christensen).

This however paves the way to disruptive innovations: a newer technology making its appearance in the background, serving primary needs in a better / more convenient way and allowing consumers at the bottom of a market access to a product or service that was historically only accessible to consumers with a lot of money or a lot of skill.

„Characteristics of disruptive businesses, at least in their initial stages, can include : lower gross margins, smaller target markets, and simpler products and services that may not appear as attractive as existing solutions when compared against traditional performance metrics. Because these lower tiers of the market offer lower gross margins, they are unattractive to other firms moving upward in the market, creating space at the bottom of the market for new disruptive competitors to emerge.” (Christensen)

In many industries, technologies improve faster than customer demands of those technologies increase. „The overlooked, underserved and seemingly unprofitable end of the market [CPU for personal computer less than $1000 in 1998] can provide fertile ground for massive competitive change.” (Andy Groove, former CEO of Intel) Time after time and industry after industry, „once the disruptive product gains a foothold in new or low-end markets, the disruptors are on a path that will ultimately crush the incumbents” ([Christensen, 2003]).

In a nutshell

- A disruptive innovation initially offers a lower performance according to what the mainstream market historically demanded,

- The new product/service is more convenient can serve a new demand

- As it improves along the traditional performance attributes, it eventually displaces the incumbent technology

Disruptive innovations are all the more effective if they can create a negative experience effect and penalize the dominant companies operating according to the business model in force. Leaders will suddenly be at a competitive disadvantage because of the very practices that have been successful in the past. The reaction therefore requires a twofold effort : learning the new rules of the game and dis-learning traditional practices ([Grandval and Ronteau, 2011]).

„not all innovations are disruptive, even if they are revolutionary. For example, the first automobiles in the late 19th century were not a disruptive innovation, because early automobiles were expensive luxury items that did not disrupt the market for horse-drawn vehicles. The market for transportation essentially remained intact until the debut of the lower-priced Ford Model T in 1908. The mass-produced automobile was a disruptive innovation, because it changed the transportation market, whereas the first thirty years of automobiles did not” (wikipedia).