Classical Tools

Give me six hours to chop down a tree

I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

There is an endless list of techniques, frameworks and tricks that have their use in strategy elaboration. Almost every new book or article on strategy, put forward a new set of analytical tools, diagnosis canvas or action frameworks.

The objective of this part is to see a glimpse of some of the most common or most used tools. The aim is not to comprehensively review themselves tools, but to get a feeling about i) how they can be used in practice, ii) what are their benefits and also iii) what are their most common pitfalls.

The SWOT analysis is one of the best-known tools, supposedly easy to use, and it is therefore very popular. People will often expect to see a SWOT and it is advisable to be ready to prepare and deliver one. This famous analysis (derived from the LCAG model) aims at assessing both internal & external factors and identifying the actions needed if the organisation is either to capitalise upon opportunities or minimise the impact of the threats.

SWOT & PESTEL

A SWOT chart can be used in a wide variety of situations, which makes it very attractive. It can for instance help evaluating the effectiveness of the existing strategy of an organisation (and defining how the strategy should be refined/adapted to changes in the environment). Adequately used, a SWOT can also be very powerful to guide the analysis and very effective to present findings.

The quality of the outputs however, may suffer when the analysis is too superficial. Improperly conducted, a SWOT analysis can be extremely subjective and misleading. Applying a SWOT on the wrong scope, failing to consider the dynamic or weak signals are among the major pitfalls.

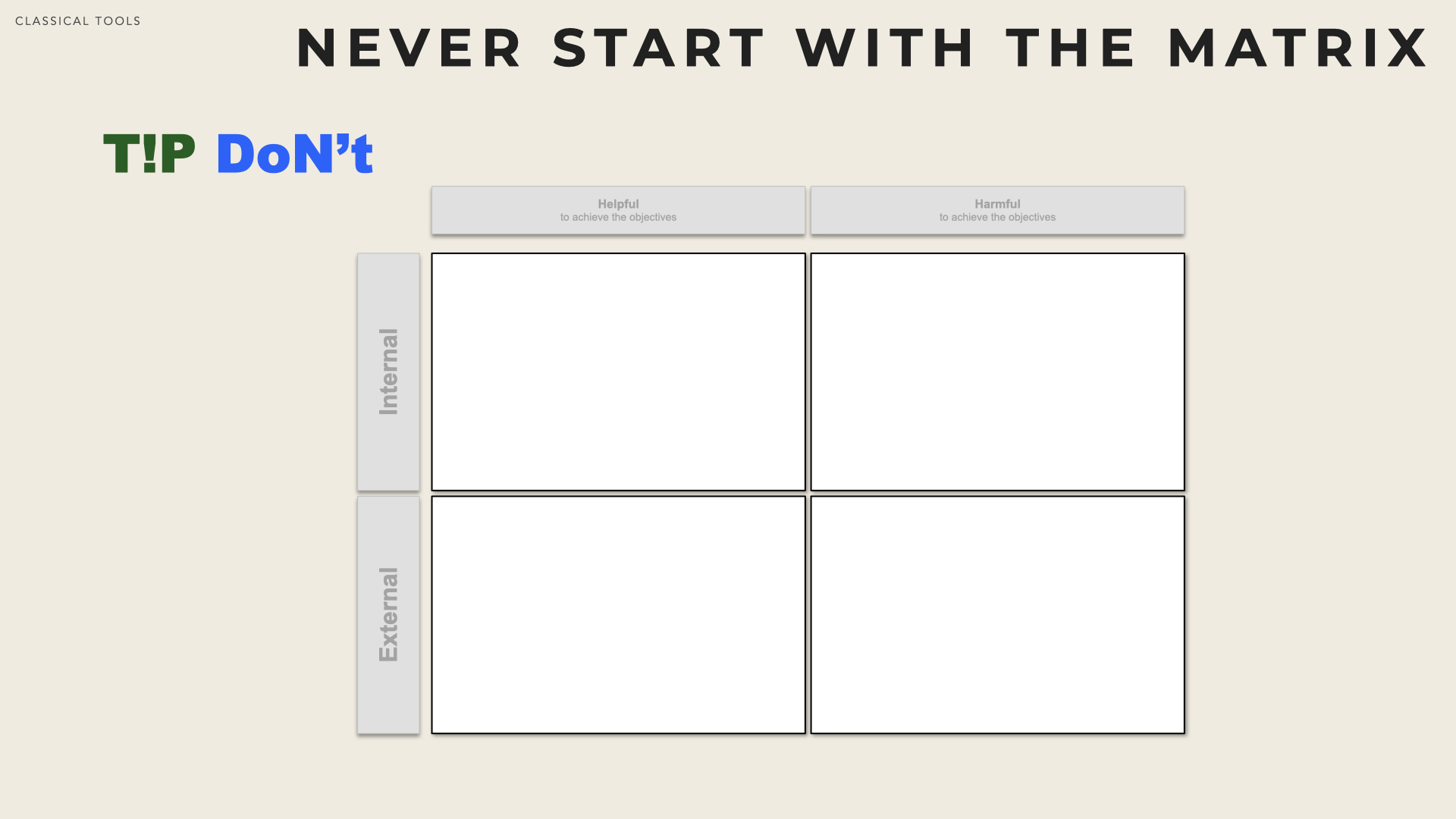

Where not to start

Barney ( [Barney91] ) notes that the well-known SWOT framework prompts to consider the strengths and weaknesses of a firm and match them with the opportunities and threats. However as the framework doesn’t suggest how strengths can be identified and appraised, SWOT sessions often turns into generating lists of what the firm is “good at” and “not so good at”.

By contrast, a SWOT should thoroughly examine:

- The External environment: its complexity and dynamic evolutions,

- The Organisation’s capabilities: what are the resources that can be mobilised by the firm. Conversely, what resources may be lacking?

- The Organisation’s strategic purpose: what is the organisation seeking to achieve? What are the criteria against which strategies must be evaluated?

- The Organisation’s culture: what are the risk of strategic drift (i.e. failure to create the necessary momentum for change).

The SWOT matrix is a good way to present findings. However other tools must be mobilised to perform the analysis and record facts and beliefs. Some of such tools and the way to use them are reminded in the following pages.

The matrix should be the result, not the starting point

In is not uncommon to try producing directly the SWOT matrix. At best it results in unjustified statements, if not false perceptions of both the environment and strategic capacities of the firm.

However it can sometimes be useful to try (and fail) to fill a SWOT grid from scratch with the project contributors. Indeed it can be a way to raise their awareness that there are many unknowns and that a sound analysis is mandatory. However, there is always the risks that people consider that the initial SWOT is sufficient and become reluctant to continue and deepen the analysis. Directly feeding the matrix can also contribute to anchor judgmental feelings.

The empty matrix – which is best known and supposedly well understood – can also be a way to explain why further analysis is needed and to introduce specific tools and analyses. The most suited combination of tools and techniques highly depends on the problem to solve, the project contributors and the available timeframe. Common tools that can be used to appraise the external and internal environments are quickly reviewed hereafter, with a focus on how to use them in practice.

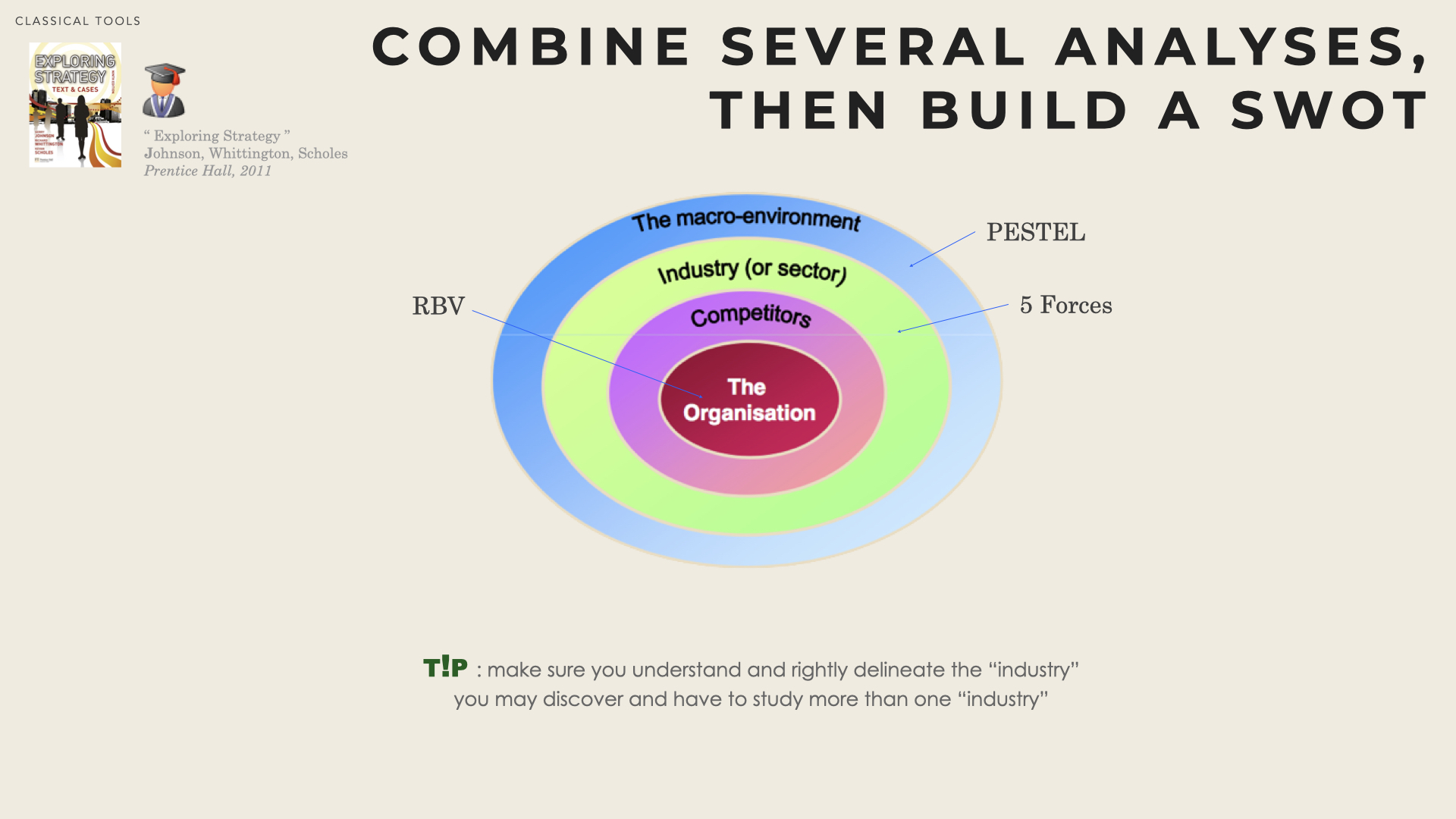

The PESTEL, 5 Forces and Resource & Competence frameworks are among the most common tools that can be used to prepare a sound SWOT analysis.

There are however some pitfalls or common mistakes:

Scope It is very easy to misidentify the right boundaries of the industry. If the scope is too wide, the analysis becomes non-specific, too general and averaged. If on the contrary, it is too narrow, then it can miss trends, weak signals and remains trapped in the status quo.

Depth Remaining too superficial and oversimplifying the situation (jumping directly to the conclusions). If you don’t learn something new from the analysis, you probably missed something.

Key factors Failing to bring out the most salient points. The aim of the analysis is to scan many items and then to down select a few factors that can “explain” the environment and its dynamic. Buzzwords & jargon should also be avoided as much as possible.

The SWOT matrix should be used to summarise the findings of more detailed analyses. It should not be a starting point.

The environment

Delineate the environment

The environment (aka organisation’s ecosystem) creates opportunities for the firm but also presents threats.

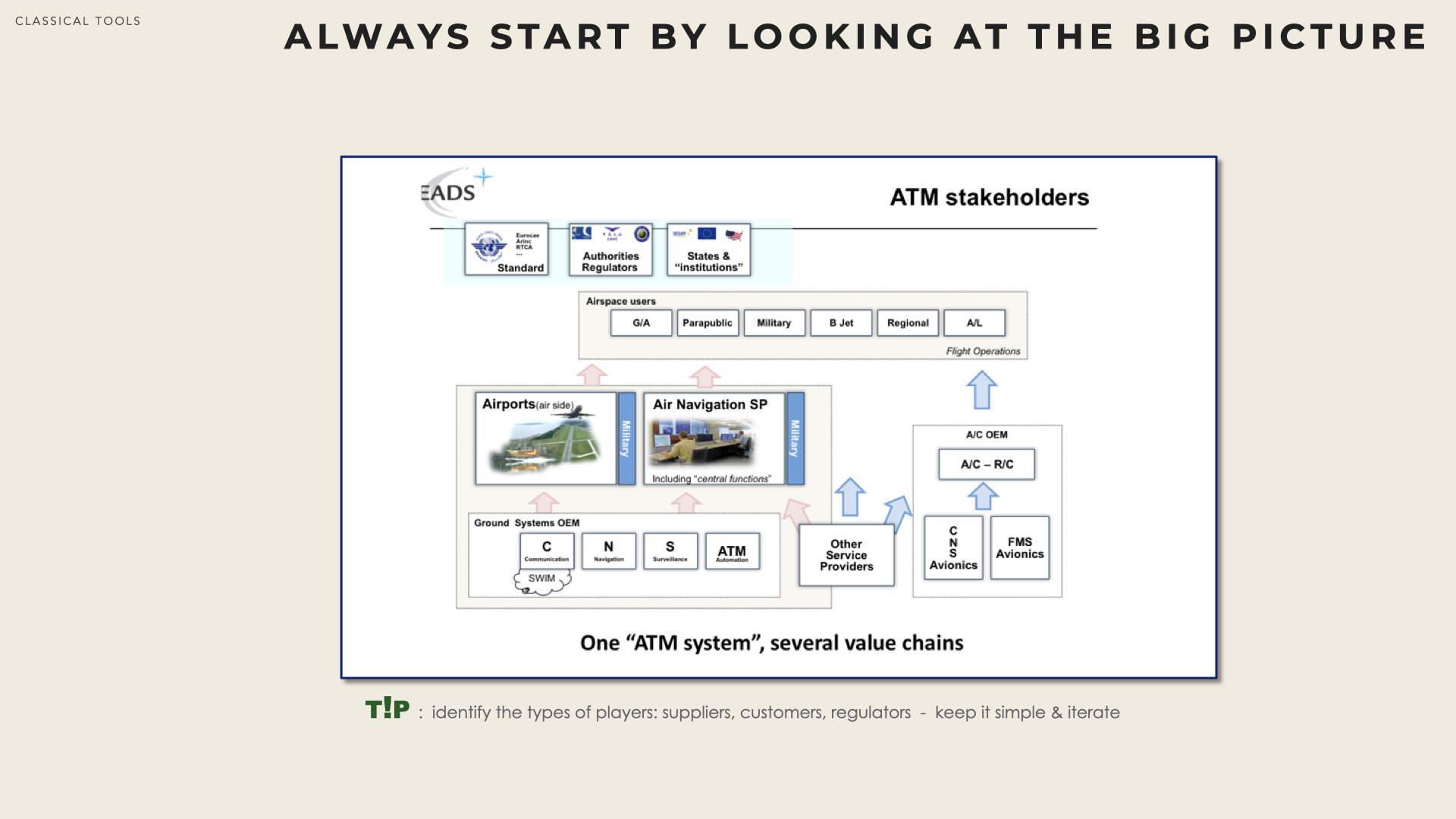

Draw the big picture The first stage in understanding the environment is to delineate the industry or industries, which requires identifying the categories of players, their activities and relationships. It is preferable to start with simplistic models (accepting to remain vague and imprecise) rather than immediately trying to formalise value systems. The objective is not yet to perform an external analysis but rather to define the boundaries.

It is always a good idea to first widen the scope. Indeed many industries are converging (former distinct industries are now becoming a single industry). Furthermore, customers of an industry may consider alternative products or services offered by different industries. In that case, competition (and therefore opportunities and threats) extends beyond the boundaries of the currently accepted industry.

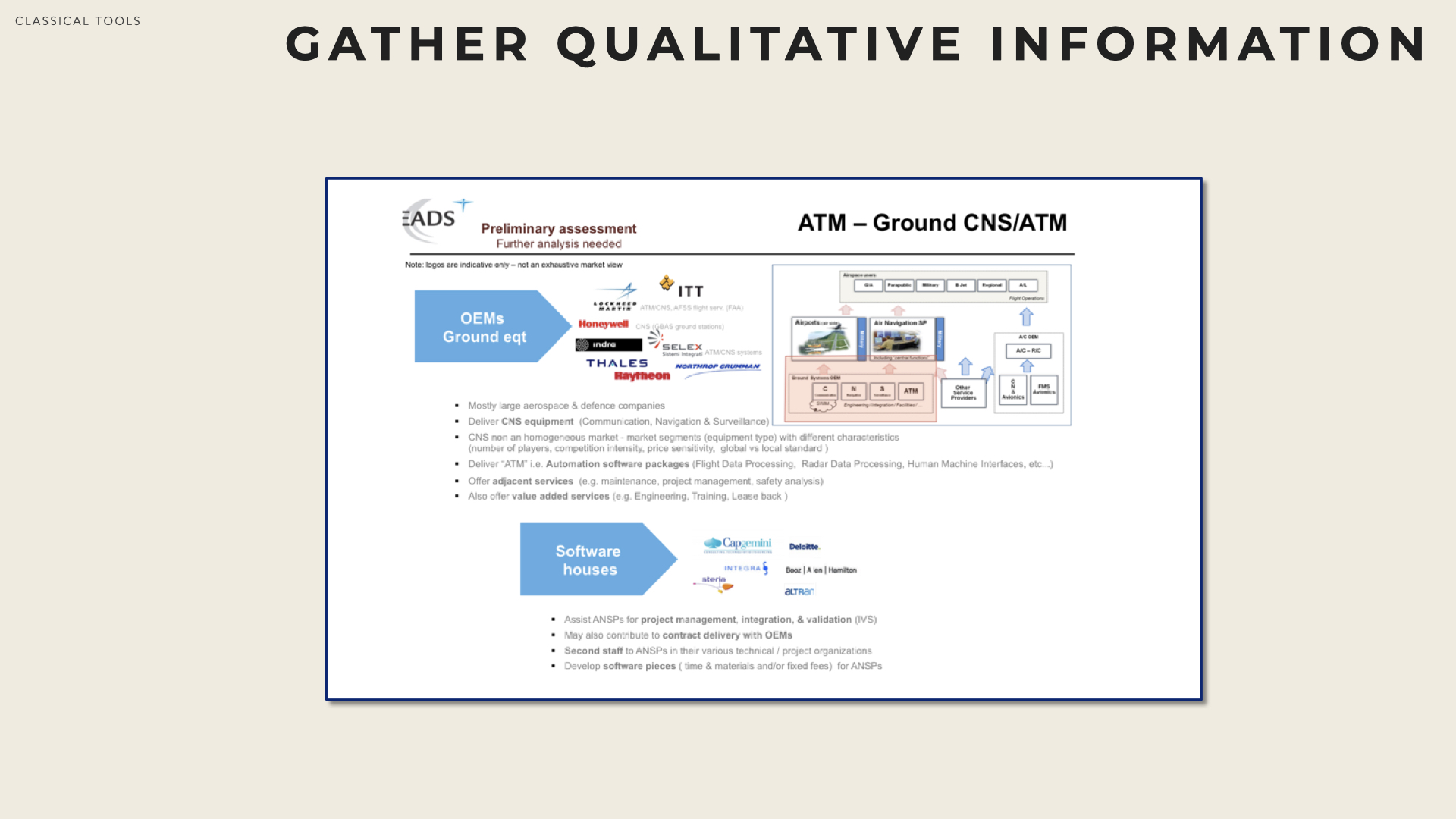

Qualitative information can then be gathered for each and every top-level element. Several sources can be considered to obtain such information:

- Annual reports, press releases, and web site of the main players,

- Interviews of experts

- Industry reports and statistics (professional association, governmental bodies, consultancies)

Competitors that are present in more than one industry, may derive a competitive advantage by combining several strategic capabilities or be in position to better benefit from evolutions of the macro-environment.

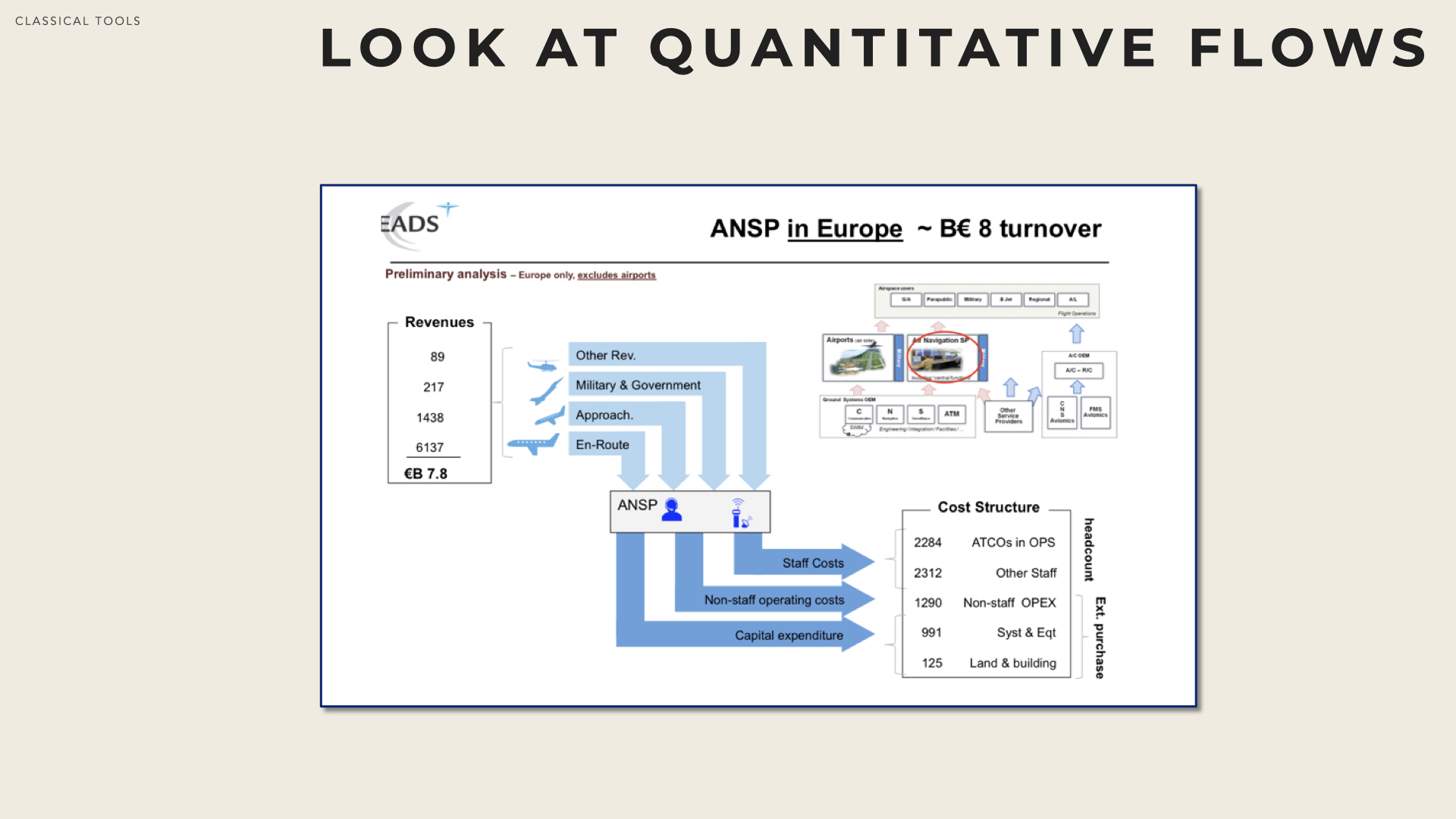

Quantitative information for instance about the main flows are very helpful to seize the big picture.

Defining the industry

Strategic analysis is about understanding how to over-perform and do better than other players. It is therefore paramount to precisely understand where you compete, what is you industry or competitive arena.

An Industry is a group of firms offering products and services that are essentially the same (i.e. are highly substitutable).

Understanding the industry may sounds easy and straightforward, but it is on the trickiest aspect in strategy analysis. Economists have classified industries (economical sectors) according to the number of players in the industry

- Monopoly a specific organisation is the only supplier of a product or service. A monopoly can be de facto (unique resource, patent, etc…) or de jure when it is established by law by a government or state. In many countries, competition law restrict dominant position and monopolies.

- Oligopoly a small number of firms dominate and control the market. Oligopolies can result from various forms of collusion (e.g. Cartel) and lead to higher prices for consumers and reduced competition among firms.

- Perfect competition a vast number of players are supplying the goods and services. The market power of each individual player is very limited. No single player can influence the market (price taker).

- Hyper competition is an extreme case of perfect competition characterised by the absence of barriers to entry and to exit. As a result there is a lot of very strong competition among companies, market are changing rapidly. It is not possible for one organization to derive and keep a sustainable competitive advantage.

Defining Market segments

An industry can be made up of several specific market segments and more of- ten than not a single industry addresses several market segments.

A Market Segment is a group of customers who have similar needs that are different from customer needs in other parts of the market.

A niche is a small segment with very few customers / business volume compared to the main market.

A strategic customer is an organisation that have the most influence over which services/goods are purchased. For instance, in the food industry, retailers are more strategic (mainly mean important here) than final customers as they decide what to purchase and distribute.

Defining Strategic groups

Conversely service/product providers can be segmented into several strategic groups.

A Strategic Group is a subset of organizations within an industry that share similar strategic characteristics, follow similar strategies or compete on similar bases.

There exist many ways to characterise strategic groups for instance:

- extend of product (or service) diversity,

- extend of geographical coverage

- number of different market segments served

- distribution channels and branding

- extend and scope of vertical integration

- grade of service (perceived quality)

- technology leadership

- size of the organisation

Strategic groups are usually mapped onto two-dimensional charts (i.e. only two key factors are considered) to stress the difference between the highest and lowest performer, for instance it is useful in

Better understanding competition the 5-forces may apply differently to different strategic groups,

Unveil strategic opportunities some spaces may be more attractive than others, or may remain unoccupied (however there might be good reasons for that if the space correspond to a black hole impossible to exploit).

Analysis of mobility barriers usually strategic groups are characterised by obstacles to movement from one group to another.

The strategic group concept helps with understanding the similarities and differences in term of competition characteristics.

Designing an appropriate model of reality

With all Strategic Frameworks, the secret reside in building a model, a simplified view of reality to highlight the key influencing factors.

It usually takes a lot of time and effort to deeply understand the various relationships between external and/or internal factors. However, every model is a simplification that introduces some biais.

„It seems that perfection is reached not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away ” (Antoine de Saint Exupery)

How to conduct a PESTEL analysis

PESTEL

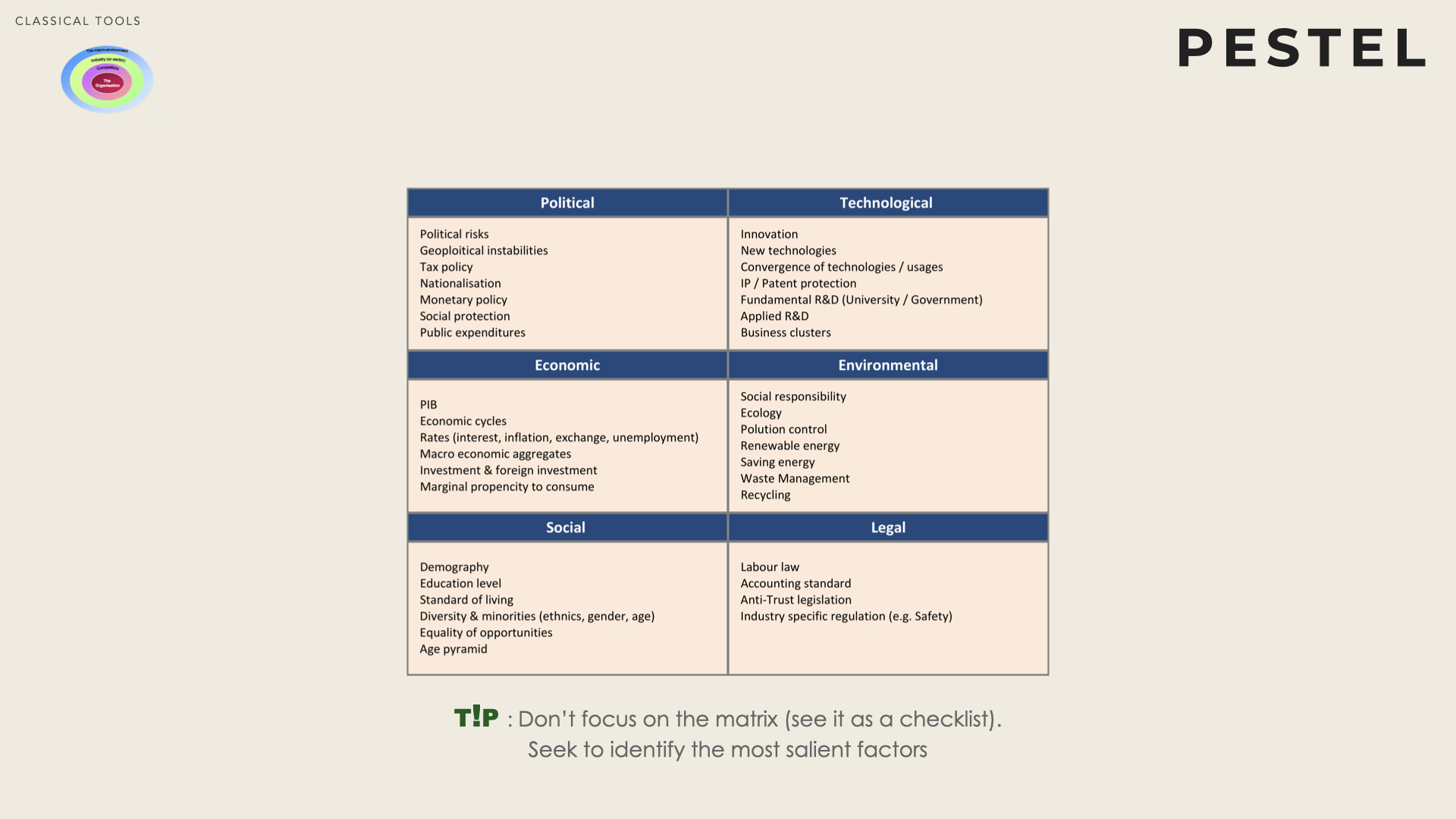

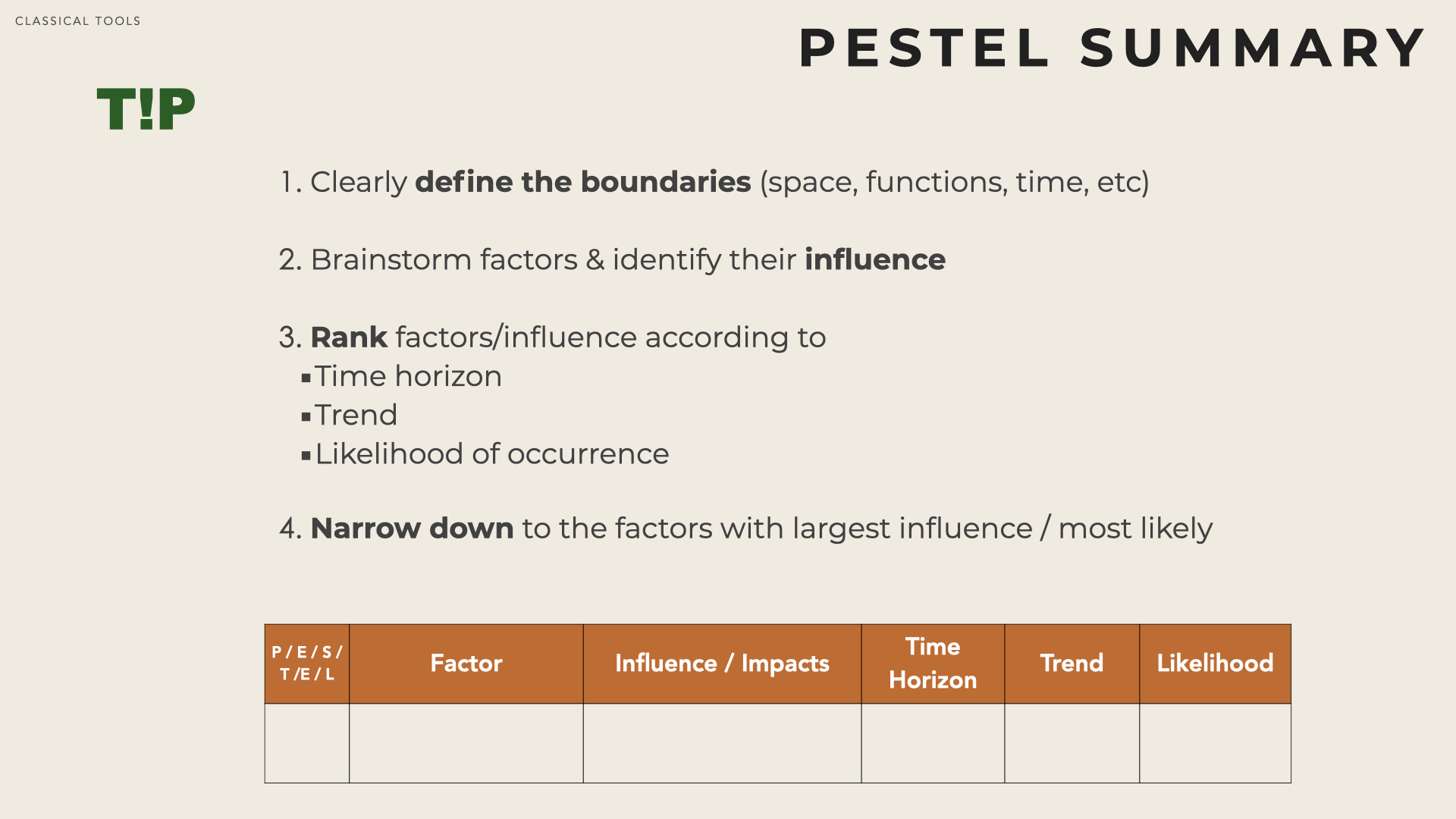

The PESTLE analysis is a tool to scan the external macro environment (big picture) in which a business operates or could operate. It aims at pinpointing which of the external factors have the biggest influence on the business (can be either positive stimulus or constraints). It is therefore important that the influence stemming from of the various factors are well understood.

Moreover a PESTLE analysis aims at deciding which of the factors can change the rules of the game in the future. The future influence of the factors – which may differ from their past influence – must therefore be forecasted. If needed several future scenarios can be worked out.

It is also essential to clearly delineate the subject and scope of a PESTLE analysis (market, industry, customer segment, geography). If needed, several analyses, on different subjects/scopes, can be performed. Always remember that a PESTEL concerns the environment and therefore, the findings apply to all the players.

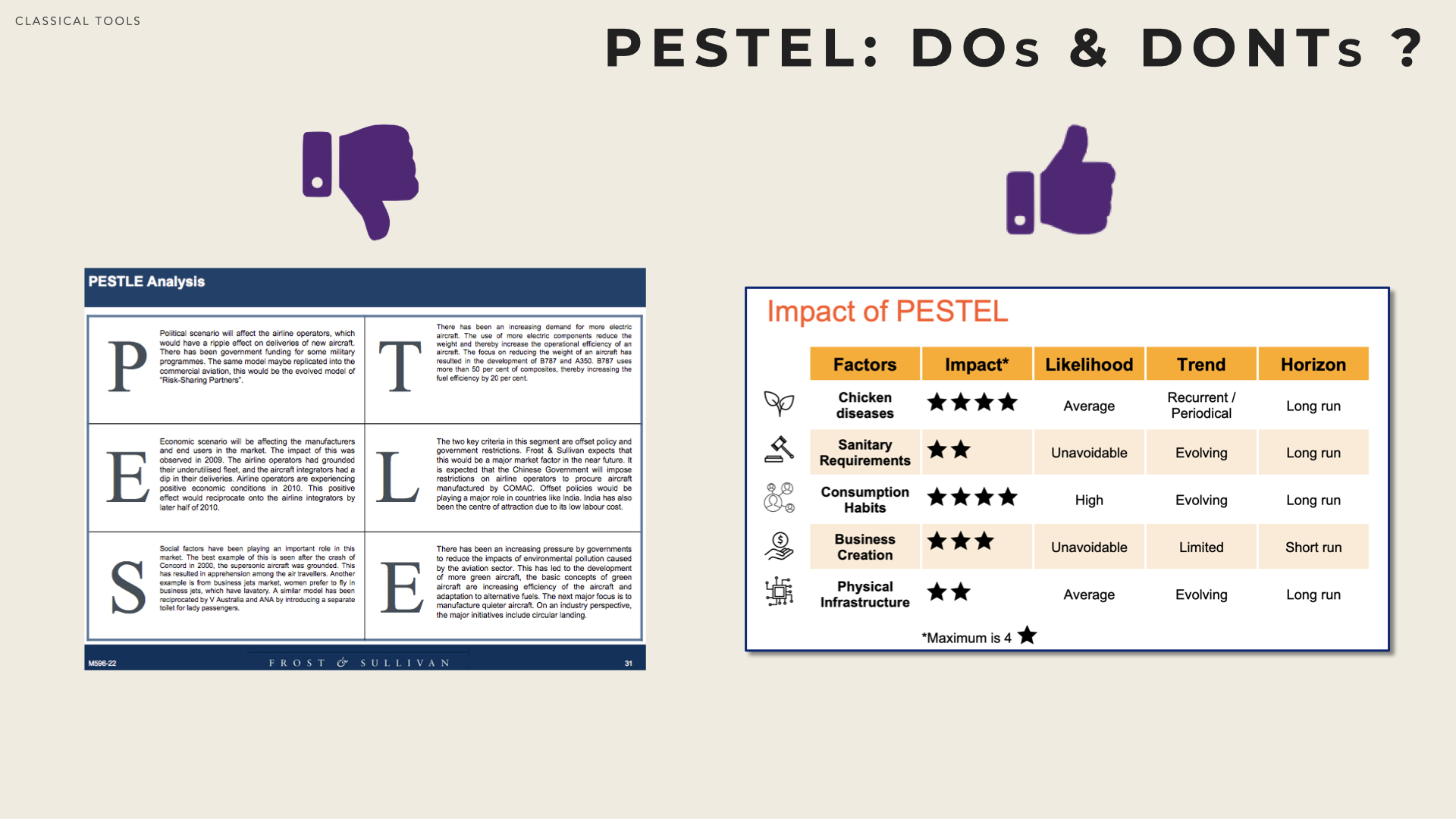

The six PESTEL dimensions (Political, Economical, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal) must be seen as a checklist. Likewise there are many lists of potential ’factors’ that can be used as guidelines. This doesn’t imply however that one factor from each and every dimension should be selected. What does matter, by contrast, is to spot the factors that have the biggest influence. In some situation all such factors may belong to a single dimension (e.g. only economical factors matter).

PESTEL HOW TO

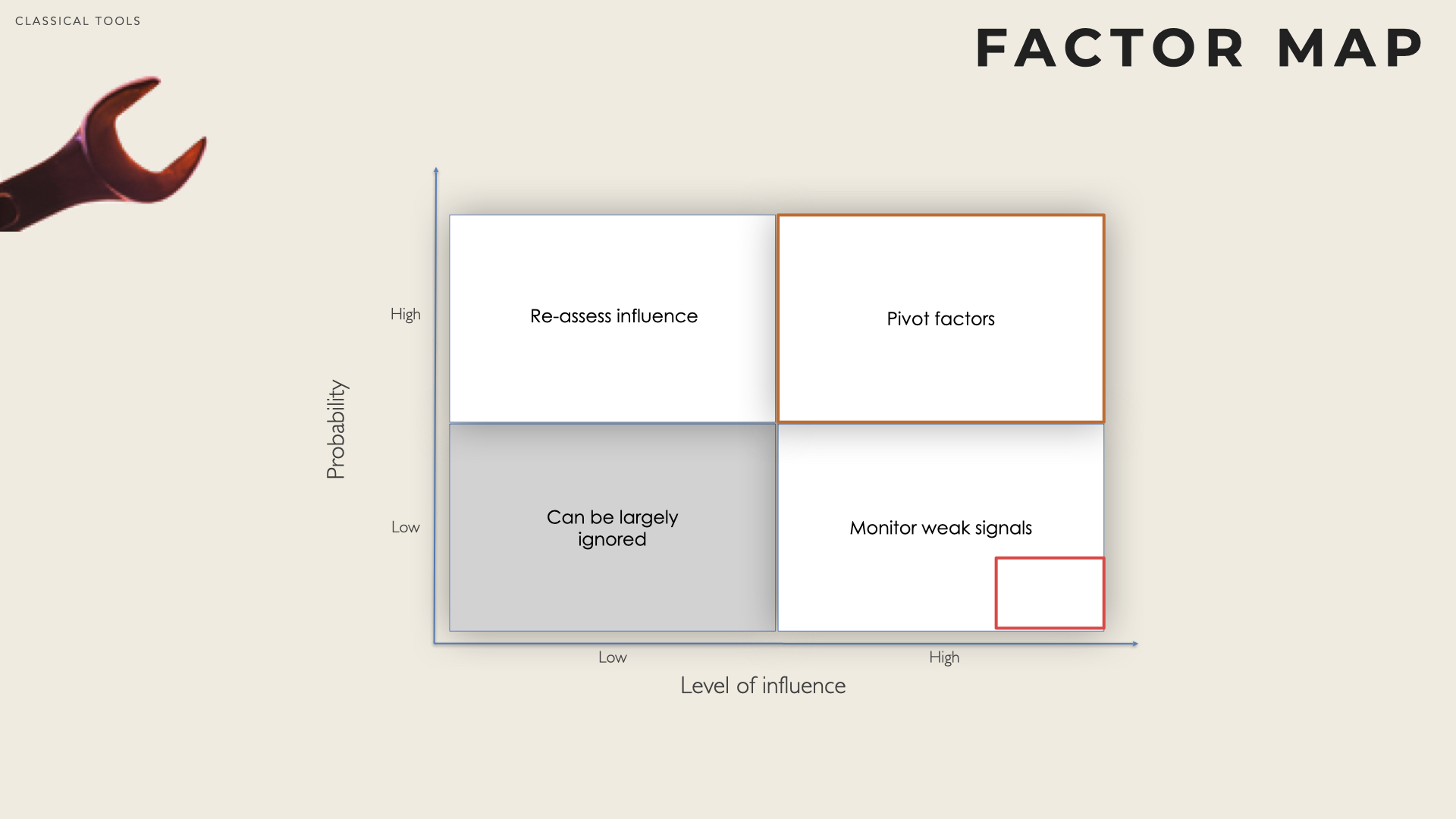

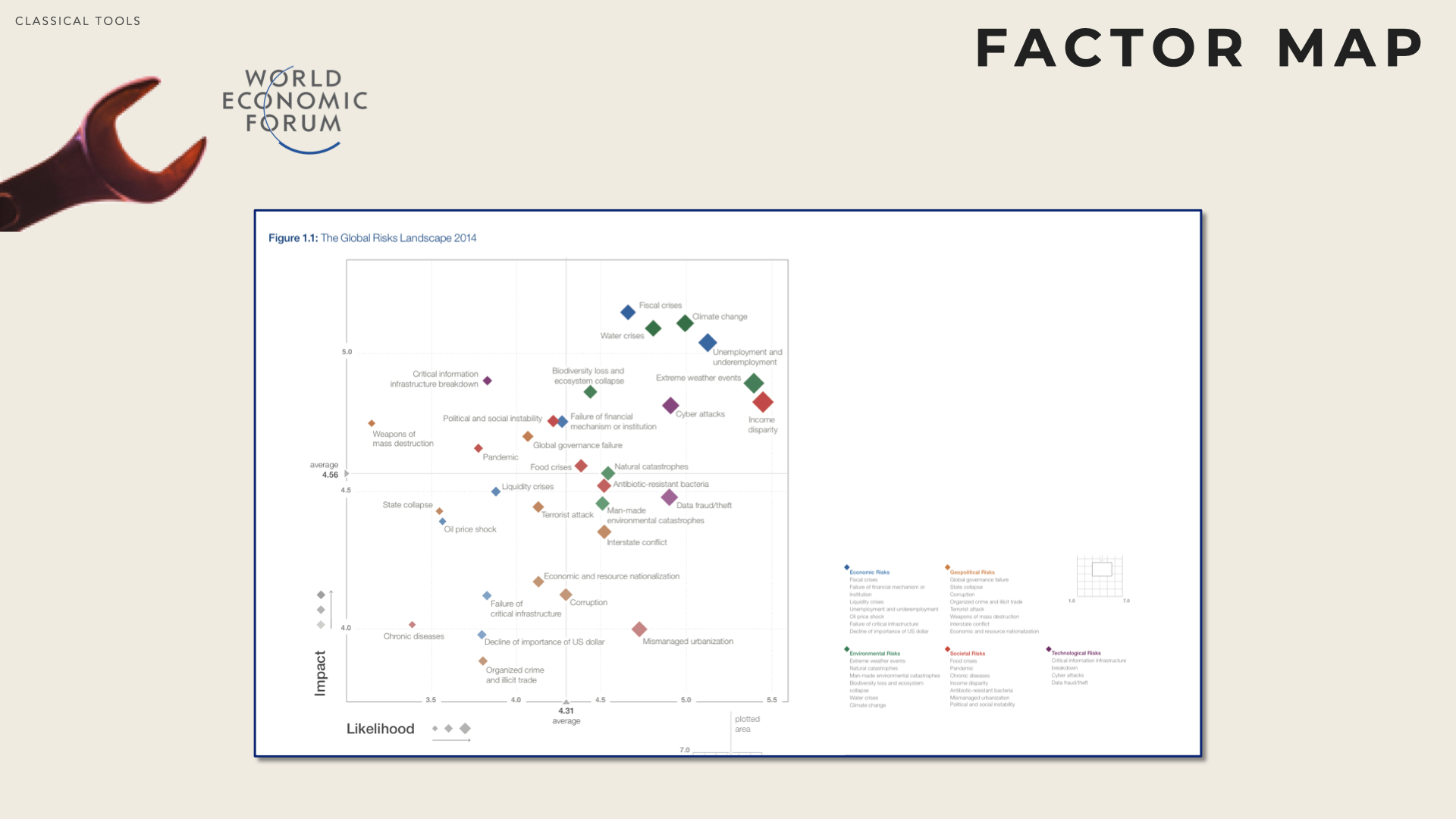

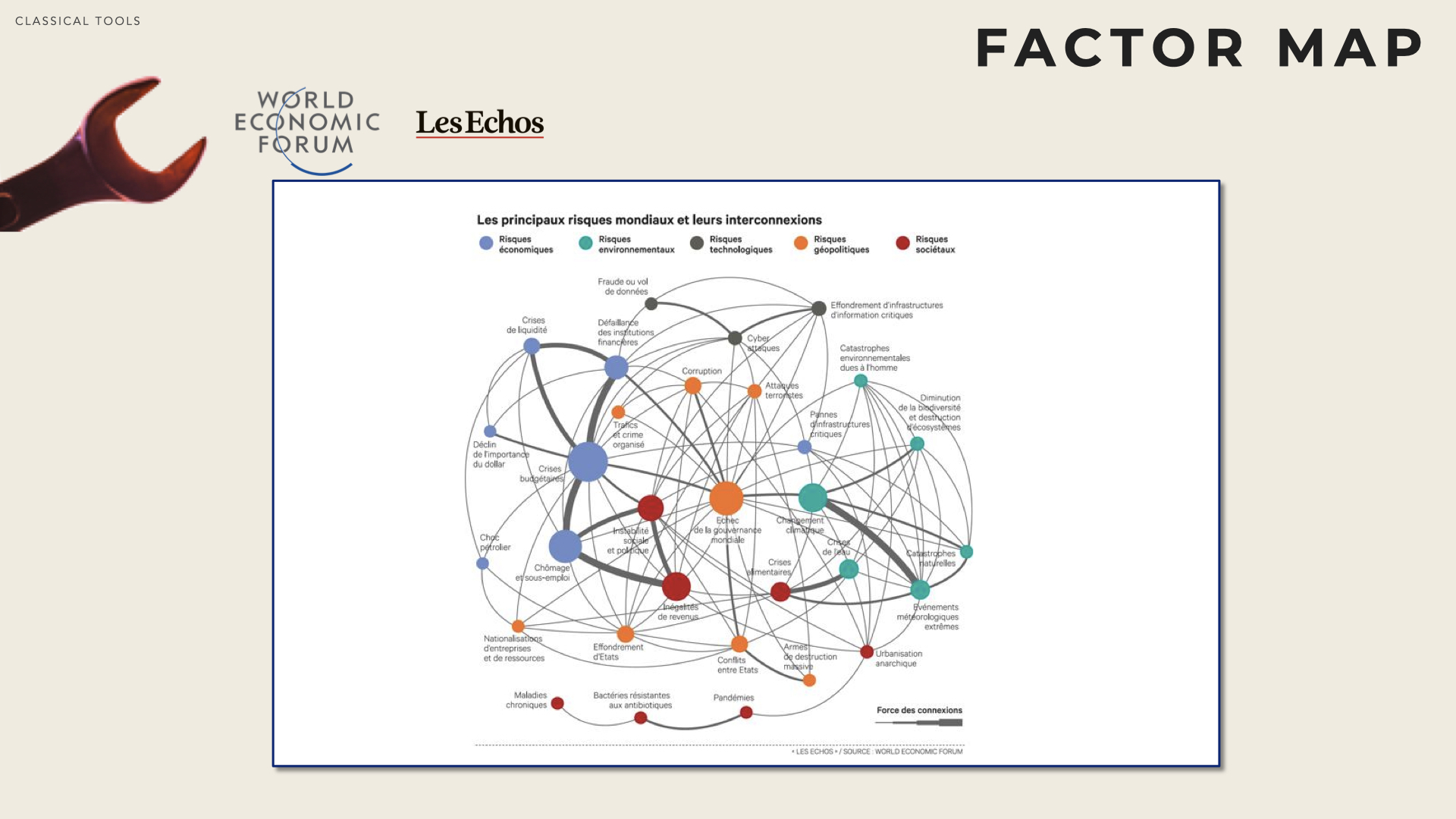

Factor Map

Facilitation techniques such as interviews, guided and/or unguided “brown paper”, questionnaires, etc can be used to brainstorm factors. When factors are identified, the implication or influence of each factor must be understood. Likewise, the time horizon at which the influence can become tangible and the probability that this occurs must be estimated.

During interactive workshops, “influences” are often identified before “factors” (i.e. the consequences before the causes). This is not an issue and can even be used as a tactics for brainstorming. However, it is important to continue the analysis until the true factors (the causes) can be pointed out.

Draw the big picture The first stage in understanding the environment is to delineate the industry or industries, which requires identifying the categories of players, their activities and relationships. It is preferable to start with simplistic models (accepting to remain vague and imprecise) rather than immediately trying to formalise value systems. The objective is not yet to perform an external analysis but rather to define the boundaries.

It is always a good idea to first widen the scope. Indeed many industries are converging (former distinct industries are now becoming a single industry). Furthermore, customers of an industry may consider alternative products or services offered by different industries. In that case, competition (and therefore opportunities and threats) extends beyond the boundaries of the currently accepted industry.

During interactive workshops, “influences” are often identified before “factors” (i.e. the consequences before the causes). This is not an issue and can even be used as a tactics for brainstorming. However, it is important to continue the analysis until the true factors (the causes) can be pointed out.

Two criteria are usually considered for the down-selection of factors: their level of influence and their probability of likelihood.

High probability / High influence These are the factors to consider in priority, as they are likely to occur (or even are already occurring) and have a significant influence upon the industry. For existing factors they probably contributed to shape the structure of the industry, as it exists today. For future factors they are probably identified by all the players and ranked as contributing to opportunities and/or threats. Influent players may even try to exercise control (individually or collectively) on some factors (e.g. lobbying, communication, etc).

High probability / Low influence These are the factors that either already exists or are very likely to occur in the future. However, they have a secondary impact or influence on the industry (for instance they complement the influence of one of the pivot factors). Such factors can be ignored, however, it is important to reassess their influence either periodically or when the analysis has progressed.

Low probability / Low influence Such factors are both unlikely and even if they occur they would have little influence on the environment. They can be largely ignored.

Low probability / high influence Such factors, although unlikely would have high influence if they occur. At the extreme, these factors can correspond to what Nassim Taleb coined a “Black Swan” : events beyond the realm of normal expectations, hard to predict and with disproportionate high-impacts. Very often such factors are part of the collective beliefs of an industry, they are implicit, and their existence (or absence) are taken for granted. However when such a factor changes, the impact on the industry can be tremendous.

Scenarios

For very global, long-term prospective analysis (e.g. Air Transport in 2050) it is extremely hazardous to estimate the probabilities of the various factors. In such a situation the few factors that are deemed to have the highest influence (e.g. fuel price, geopolitical stability, demand for transport) are considered in priority. Then the potential outcomes for each and every factor must be defined – usually only ”extreme” outcomes are kept (low fuel price, high fuel price, extremely high fuel price).

The various combinations of factors/possible outcomes correspond to a potential scenario. The objective here is not to predict but to encourage managers to be alerted to a range of possible futures.

Although simple in its principles, this technique is extremely difficult to use in practice, due to its rapid combinatorial explosion. With too few factors, the analysis remains naive; with too many it quickly becomes unmanageable. In practice, analyses are limited to a very few factors (2 – 3 factors). The value lies in the process of exploration and contingency planning that the scenarios set off.

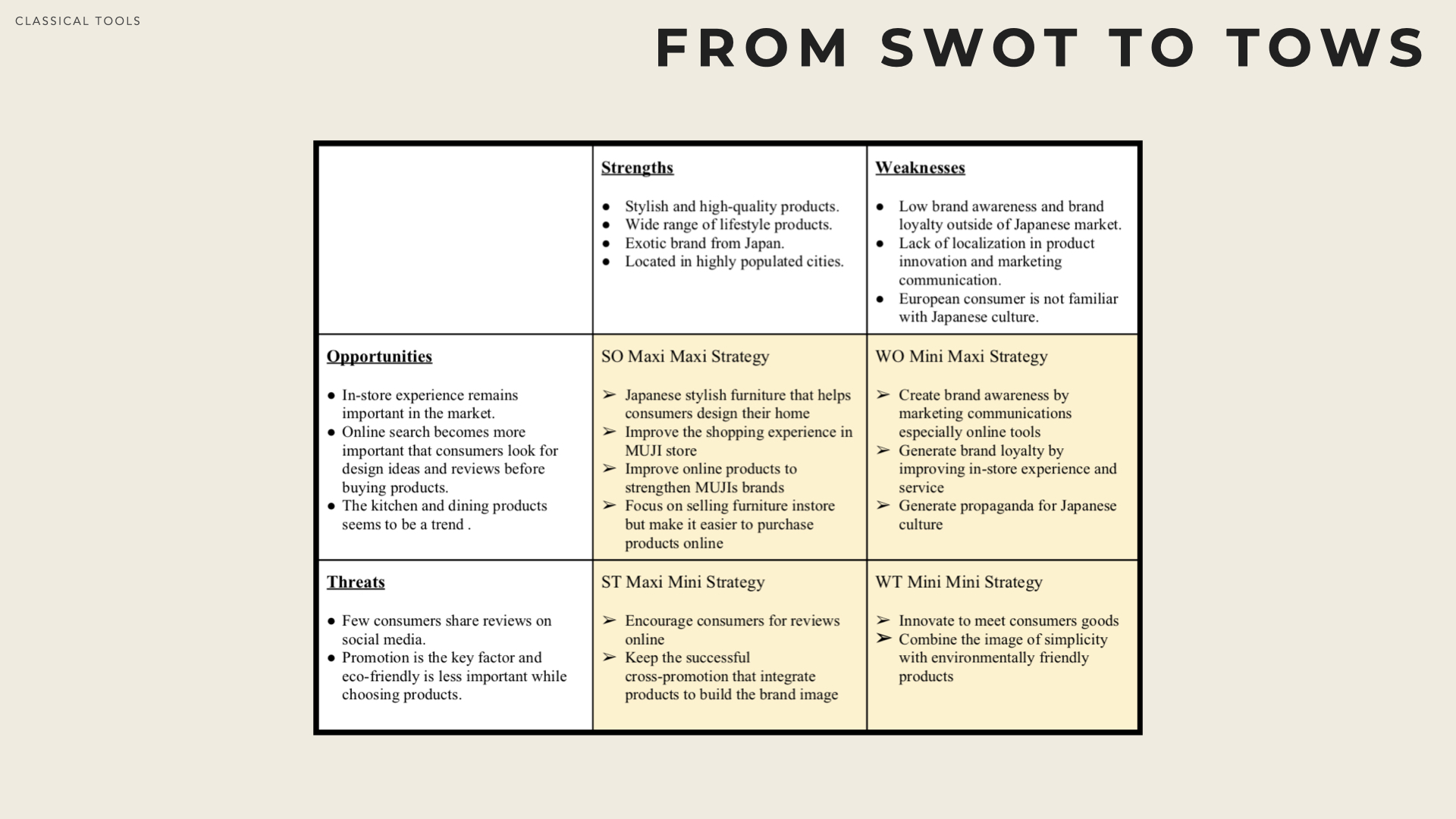

From SWOT to TOWS

Once built, a SWOT matrix can also be used to fine tune the analysis of the situation and refine the strategic options. Typically, strategists would look at how to increase competitive advantages by matching the strength and opportunities, while trying to convert weaknesses or threats into strengths and opportunities.

The four quadrants of the matrix correspond to four distinct responses:

Exploit Opportunities in area of Strength: leverage existing strength, offensive expansion mode,

Search Opportunities in area of Weakness: reduce the weaknesses and develop new strength to exploit the opportunities, defensive expansion mode,

Confront Threats in area of Strength: use existing strengths to mitigate threats and get protected, pure defensive mode,

Avoid Threats in area of Weakness: reduce internal weaknesses to become less vulnerable to environmental threats – repositioning strategy mode.

Understanding the four quadrants and their consequences can lead to revisiting the strategic objectives and/or discover new options or key realisation steps. The purpose of strategy formulation is to develop a strategy that will take advantage of the opportunities and overcome or circumvent the threats.