Getting Organised

Strategy elaboration is likely to mobilise a wide variety of techniques, involve staff from various functional origins and last from a few weeks to several months. It is therefore paramount to anticipate, plan and organise the work to ensure that resources and means are well aligned with expectations and constraints.

Preparing a report, within a week, on the structure of an industry is not comparable with elaborating, along several months, a full diversification case. These differences must be reflected in the way resources are allocated and the work is planned.

Activity types

As already mentioned, there is no magic formula and no ready to use recipe. Consequently the artefacts to be generated (documents, dossiers, deliverables, etc.) are highly dependent on the specific context. Therefore, predefined lists of deliverables would be of little use.

Nevertheless, it is highly advisable, when preparing a specific deliverable to consider that it should belong to exactly one of the five following categories. Indeed, mixing or messing the categories (i.e. using a deliverable for the wrong purpose or failing to calibrate the deliverable - which is one of the most frequent pitfalls) can be very detrimental.

Organise the work - this category addresses neither the solution, nor the problem. It exclusively deals with problem-solving aspects. Artefacts from this category can include elements such as: the description of the specific elaboration process, the definition of responsibilities among contributors, templates & guidelines to be used for the production of other deliverables. In other words, it deals with planning the strategy-making project.

Brainstorm ideas - elaborating strategies requires creativity, exchanges and challenging ideas. Several tools & techniques can be used to stimulate and trace such exchanges. The resulting outputs must be seen as intermediate products. These outputs do contribute to strategy elaboration although they should not be confused with ‘recommendations’. Some of these items can populate the ‘facts & beliefs’ categories. In such instances, it can be advisable to double check and/or look for complementary information. It is also usually necessary to reword and restructure the various items.

Register facts & beliefs - it is mandatory (although often overlooked) to register & trace the various facts and beliefs upon which a strategy is built. For each item, the source (or origin) of the information and possibly a factor of confidence must also be recorded. In some cases, simple lists or tables can be sufficient. In other instances a structured database can be more appropriate. When quantitative data are computed from large sources (data crunching) it is advisable to keep a copy of original data and computation formulas, in case it would need to be revisited.

Findings - based on ideas, beliefs and facts, strategists prepare findings. Findings are not yet recommendations. They consist in synthetics views drawn from the various elementary items previously gathered. Findings are very often presented as matrices & charts with the objective of offering synthetic and visual understanding of a situation. It can sometimes trigger further analysis when outcomes must be confirmed or consolidated. A very common pitfall, is to confuse “findings” with “recommendations”.

Recommendation - is the main outcomes of strategy elaboration. Findings are used to justify and illustrate the recommendations. However recommendations should not consist in a series of ’findings’ (typically matrices, graphs, figures, etc). On the contrary, a strategic recommendation should tell a story. It should be intelligible for all stakeholders (in particular for those who don’t understand the jargon of strategy).

Planning a strategy-formulation project

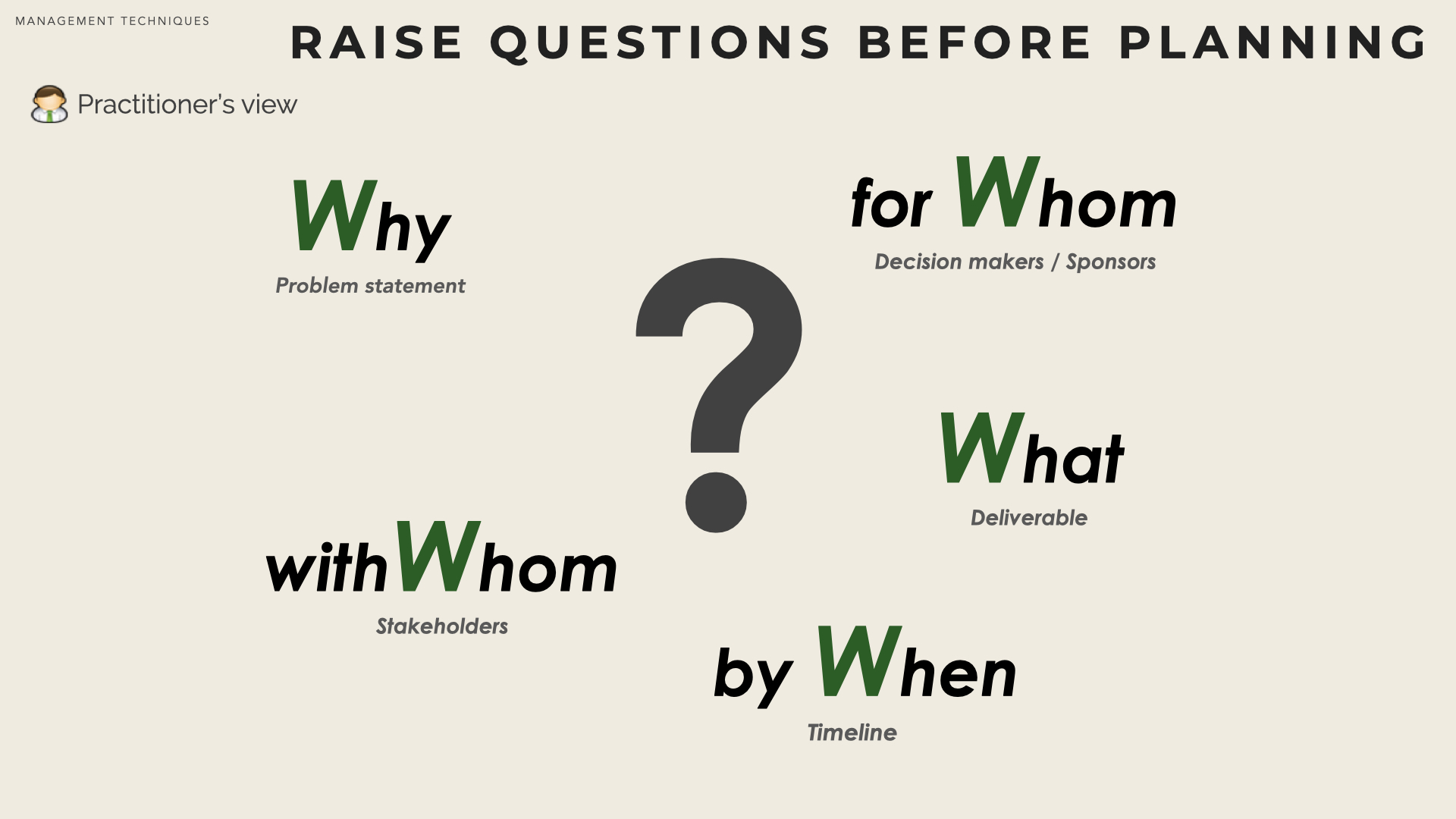

First, consider the “W”

It is usually wise to make sure that the Why, for Whom, What, by When and with Whom are sufficiently understood before attempting to defining the How. It is therefore, paramount to explicit all the facets of the ”problem” before trying to solve it.

Problem Statement - (mis-)understanding or (mis-)stating the problem (why do we need to formulate a strategy, why now, about what precisely, etc..) is often the Achilles’ heel of strategy-making. As initially presented (ex-ante statement) many aspects of the problem can be implicit or even unsuspected. Delineating accurately the problem to be solved is the best way to find how to rightly solve it. This cannot always be fully achieved during initial planning. In that case, activities to refine the problem-statement must be planned.

Decision makers - knowing who the decision makers are, what they expect from the project, what they already believe or (think they) know is also absolutely essential. Getting direct access to the ’sponsors’ of the project and checking their expectation is preferable although not always feasible. It doesn’t necessarily imply that the formulation should confirm their convictions. Nevertheless, it is wise to be aware in advance, if the recommendations won’t fit their beliefs.

Deliverables - identifying beforehand, what are the artifacts to be produced is also absolutely key for planning. As already mentioned several types of artifacts must be considered and not all of them are intended for final presentation. Notwithstanding that, visualizing the final deliverable(s) helps calibrating the strategy formulation project, identifying the contributors and the level of effort.

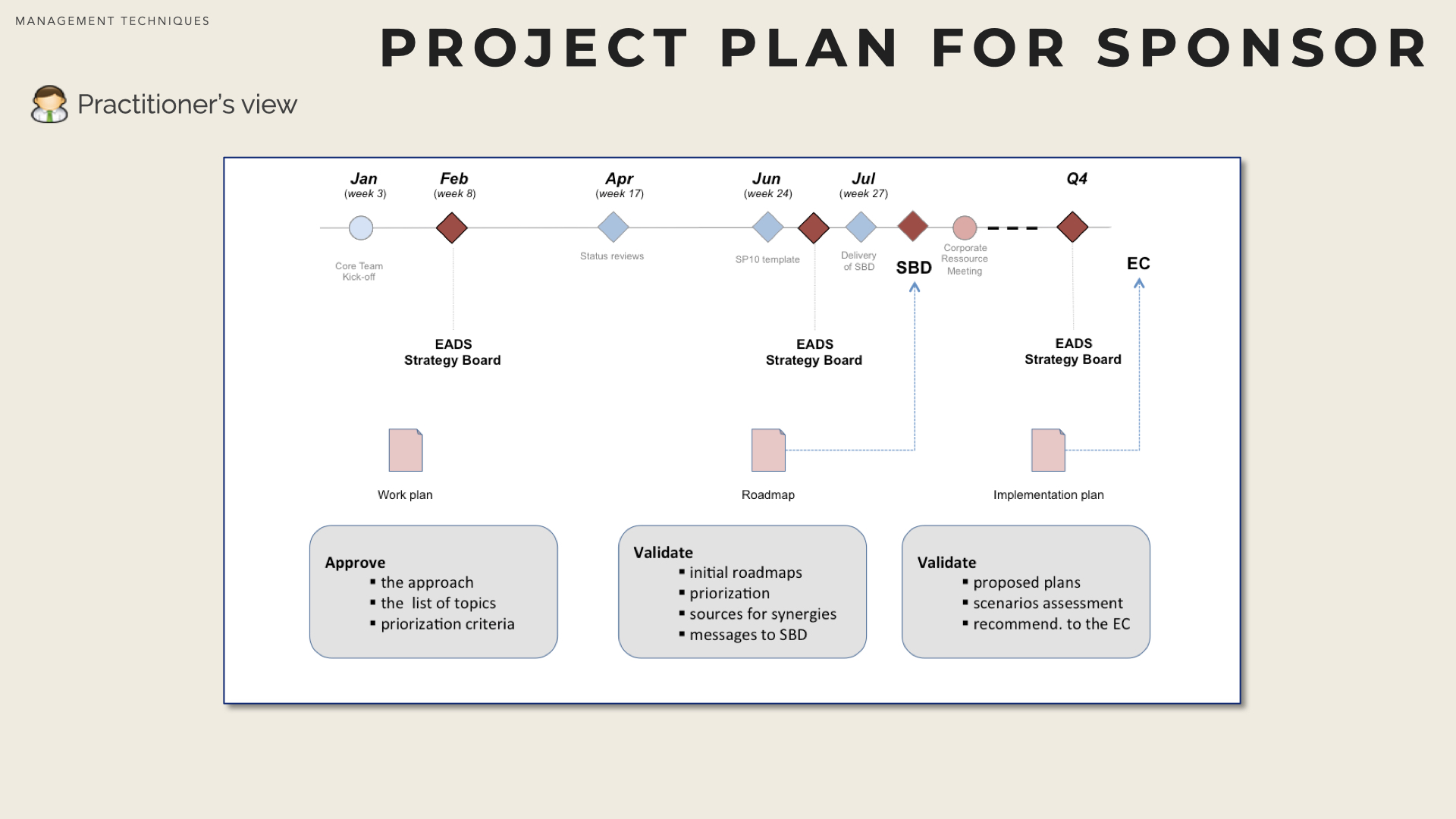

Timeline - agreeing with the project sponsors on the project timeline is also absolutely necessary. More than getting absolute dates, it is crucial to know if the strategy formulation project must get synchronized with other events (e.g. strategic planning process, board meeting, etc). It is noteworthy that in strategy elaboration, deadlines tend to shift “to the left” and delays to shorten. That can be an issue with purely sequential methods and it is one of the reasons why more iterative approaches (series of successive refinement loops) are often advisable.

Stakeholders - last but not least, it is fundamental to detect who holds stakes in the project. Identifying the contributors to a strategy elaboration is a by-product of project planning. Nevertheless, additional people must usually also get involved to ensure success and smooth the buy-in of the recommendations. These persons must be identified very early, and the way they will interact with strategy elaboration (e.g. interviews, workshops, reviews, etc.) must be carefully planned.

Defining the How

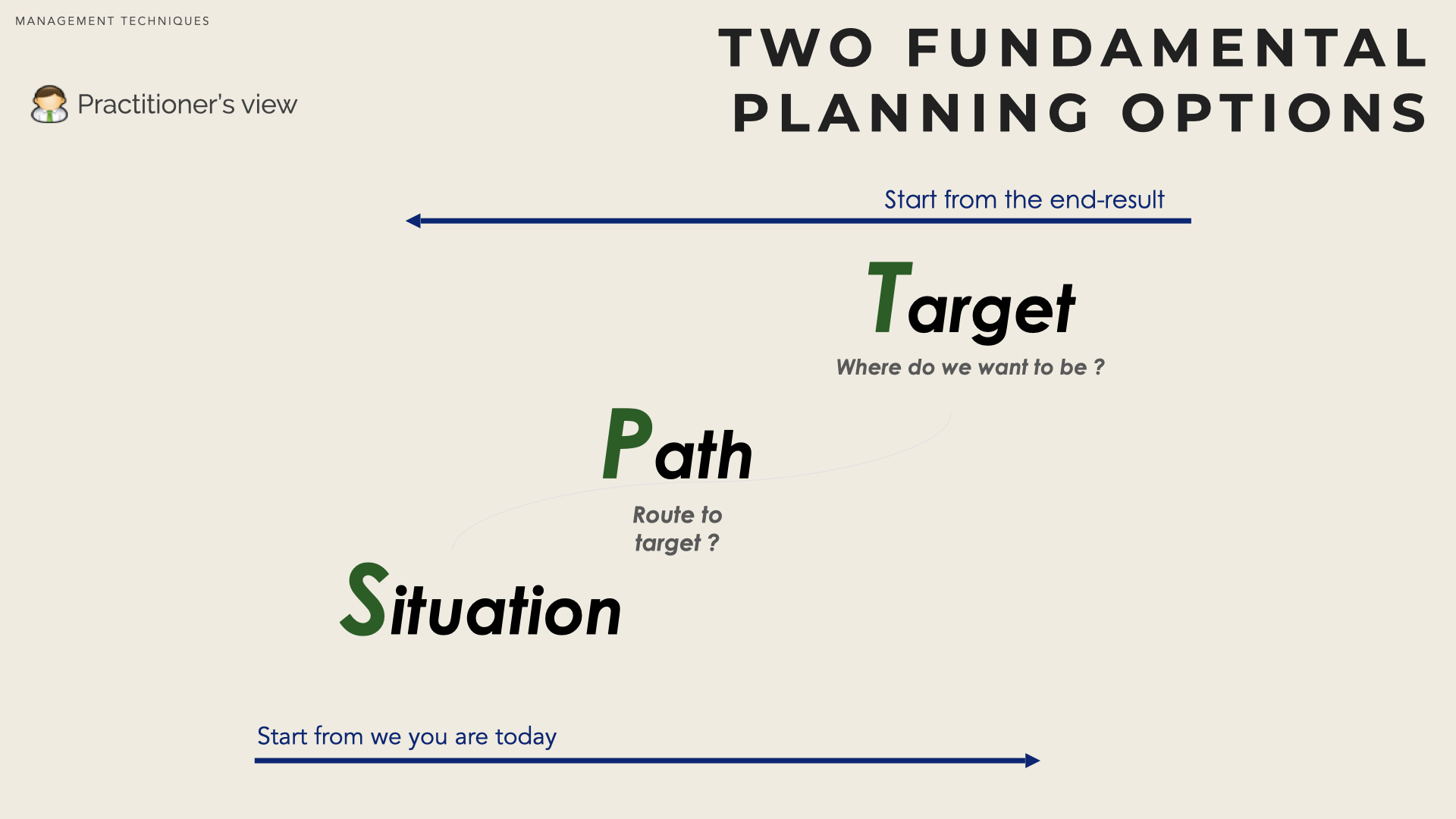

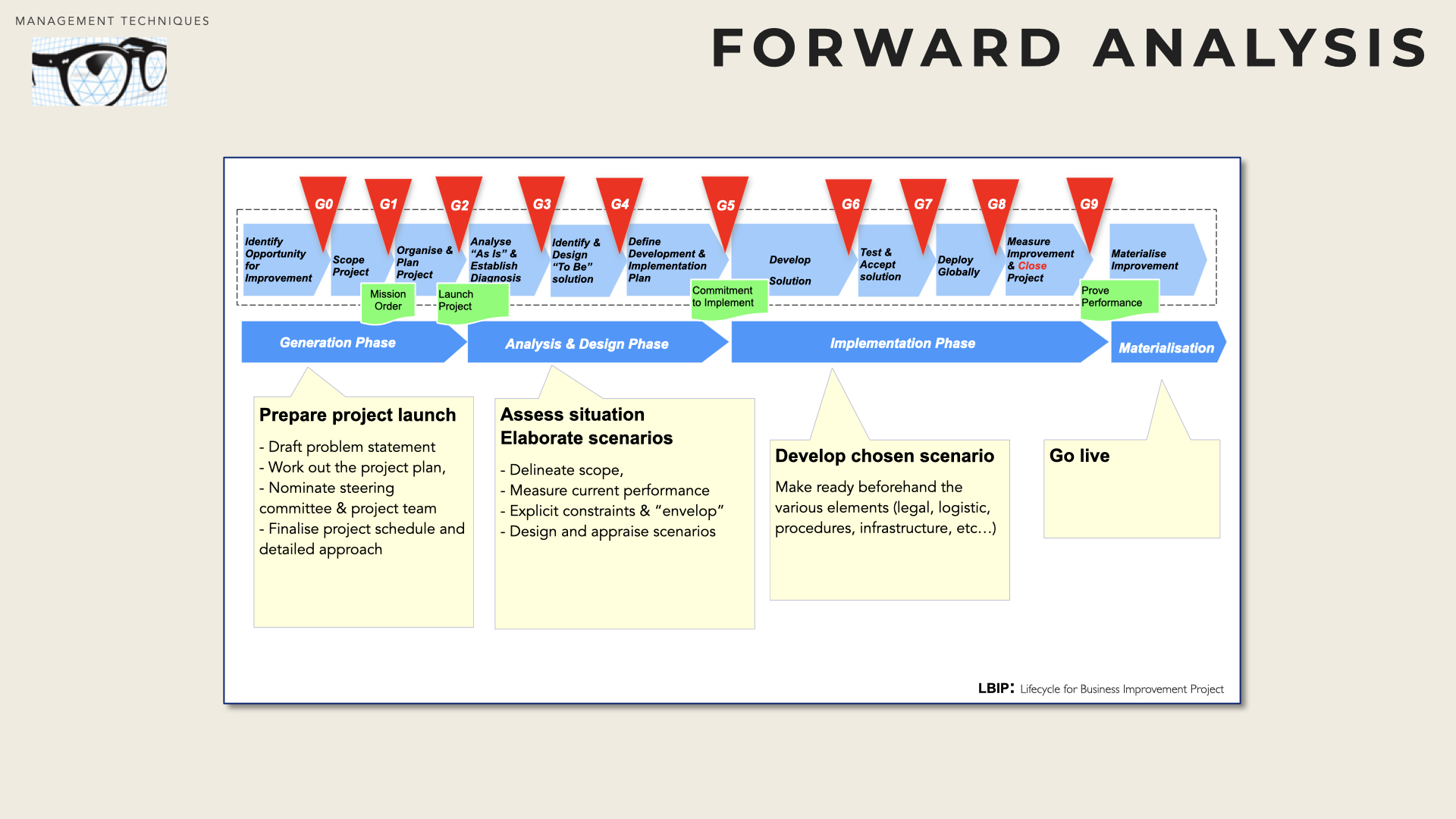

There are many approaches to strategic elaboration, but they all include some sort of evaluation of the current situation (analysis, diagnosis), identification of the target state(s) (future, ideal state or position) and definition of a route from current situation to future expected state.

This is often summarised by the three following questions:

- Situation Where are we today? What is our current state?

- Target Where do we want to be in the future? What is our target ?

- Path What route(s) can lead us from our current situation to target?

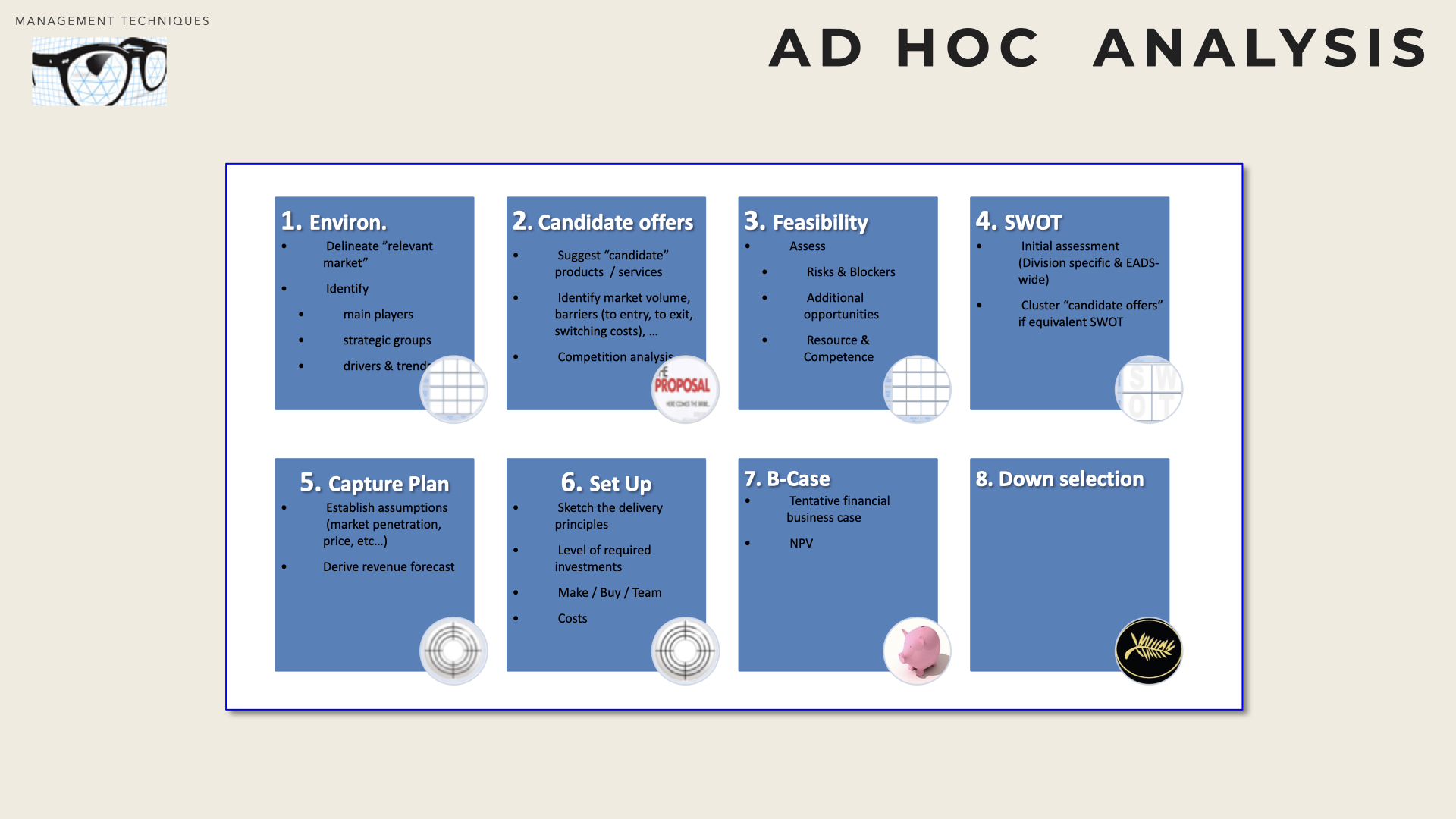

There are basically two categories of methods:

- Start from the current situation - first establish a comprehensive picture of the current situation of the firm and its environment. Answer thoroughly the question ”where are we today?” and from there, tackle the question ”where can/shall we go tomorrow?”. These methods implicitly suggest that an acute and accurate analysis of the current situation can reveal the precise strategic goal that the firm should pursue and the best path to get there. To some extend, these methods insinuate that the best strategic move is fully determined by a given situation. Hence, the role of the strategist would be to read from the internal & external environment (like fortune-tellers can predict destiny from cards?).

- Start from the candidate target state(s) - start from drawing an image of the ideal desired state(s), before mapping a possible route from the current situation toward the target to which the firm is aspiring. First address the question ”where would we like, ideally, to be tomorrow?” and then work out a path to that target, considering the gap from today’s situation. Much room is left for intuition and strategic leaps. However, the ”ideal target” may seem to come out-of-the-blue and is usually more an input to than and outcome of the analysis. Yet, these methods are well suited to optimise and refined an already potential strategic moves.

Different methods and approaches can be blended, so to leverage their benefits and compensate their shortcomings. That is an additional reason for planning: the right combination of tools and methods depends upon the problem to be solved. Generally speaking, one can take full advantage of forward analysis methods to scan and identify candidate targets. Then backward reasoning methods can be used to refine and dispute the validity of the candidate targets.

Some practical tools

Planning

When confronted to planning, most people seek to build a Gantt chart. This is usually not necessary and often a bad starting point. The key is by contrast to identify the key deliverables and associated milestones.

A good way to approach planning is to identify what decisions/actions must be taken and by whom. The various deliverables must then be sequenced and designed to allow these decisions/actions.

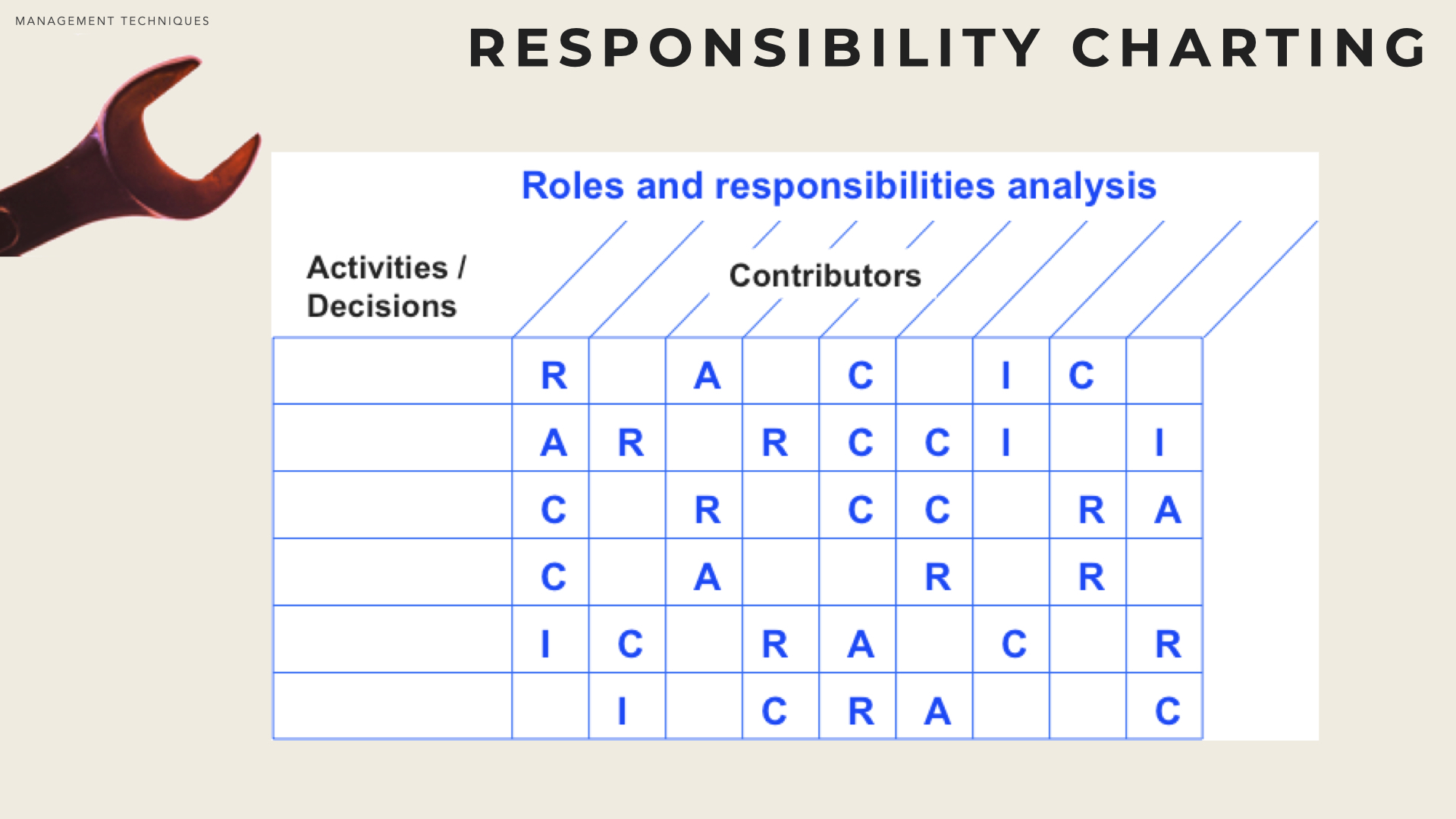

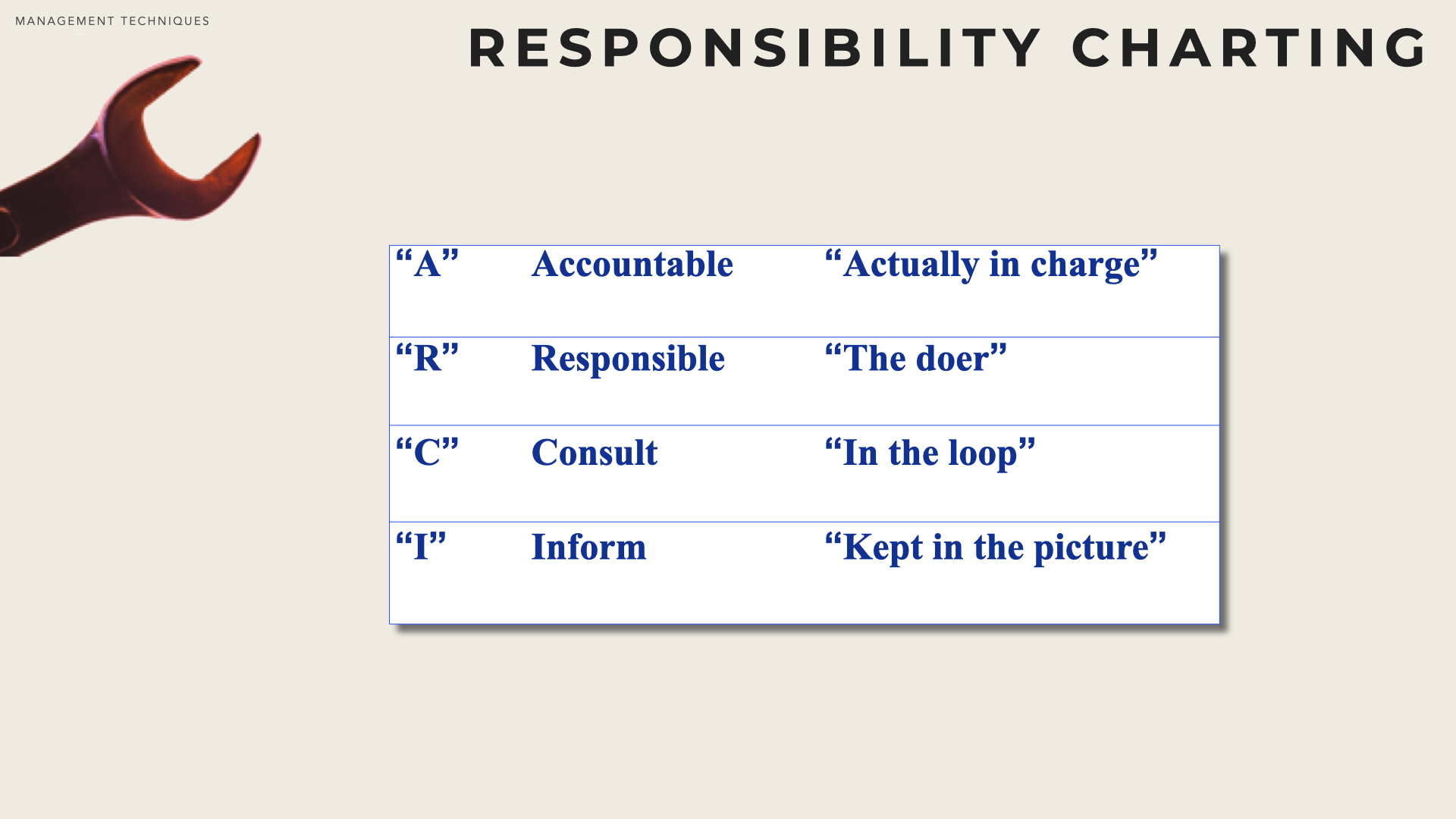

Responsibility Charting

Responsibility charting (or RACI chart) is a technique to identify key activities and clarify the role that each contributor must plays in relation to those activities.

It identifies accountabilities, reduce misunderstandings, eliminate duplication of efforts and encourage teamwork.

It is a table that lists the activity items and their contributors. The activities must produce an output and their names should begin with an action verb (e.g. validate, estimate, check, find, etc).

Contributors are allocated to activities with a specific role: Accountable, Responsible, Consulted or Informed.

Accountable - the person in charge and ultimately responsible for the activity, task or decision. He or she puts his / her head on the block. This includes yes/no authority and veto power. One and only one ’A’ should be assigned to an activity. A person who is ’A’ for one activity can have other roles for other activities.

Responsible - the doers, the persons who complete the task. Responsibility can be shared and several ’R’ can be allocated to one activity. However the number of ’R’ on one activity should remain limited. Otherwise it can be the sign that the activity should be split in several sub-activities or that some ’R’ should be ’C’ or ’I’ instead.

Consulted - the persons who must be consulted prior to the action or decision. Consultation can take several forms such as interviews, work- shops, etc. ’C’ people (they can be experts, decision-makers or anybody with a high interest/high power) will provide inputs, guidelines and/or constraints to ’R’ people.

Informed - the persons who must be kept informed after a decision is made or an action is completed. When the opinion of somebody must be taken into account then he/she cannot be only ’I’ (must be at least ’C’). ’C’ + ’I’ is a very common combination: the persons must be consulted prior to the action and then will be informed once the action has taken place.

A usual pitfall however can be to multiply the contributors and to introduce ’checkers checking checkers’.

In strategy, Responsibility charting is not limited to project establishment. A ’RACI’ can be used for a wide variety of situations, such as establishing governance rules either within a firm (organisation, responsibility charts between departments and units) or between a firm and its environment (supply chain, strategic alliance, etc).

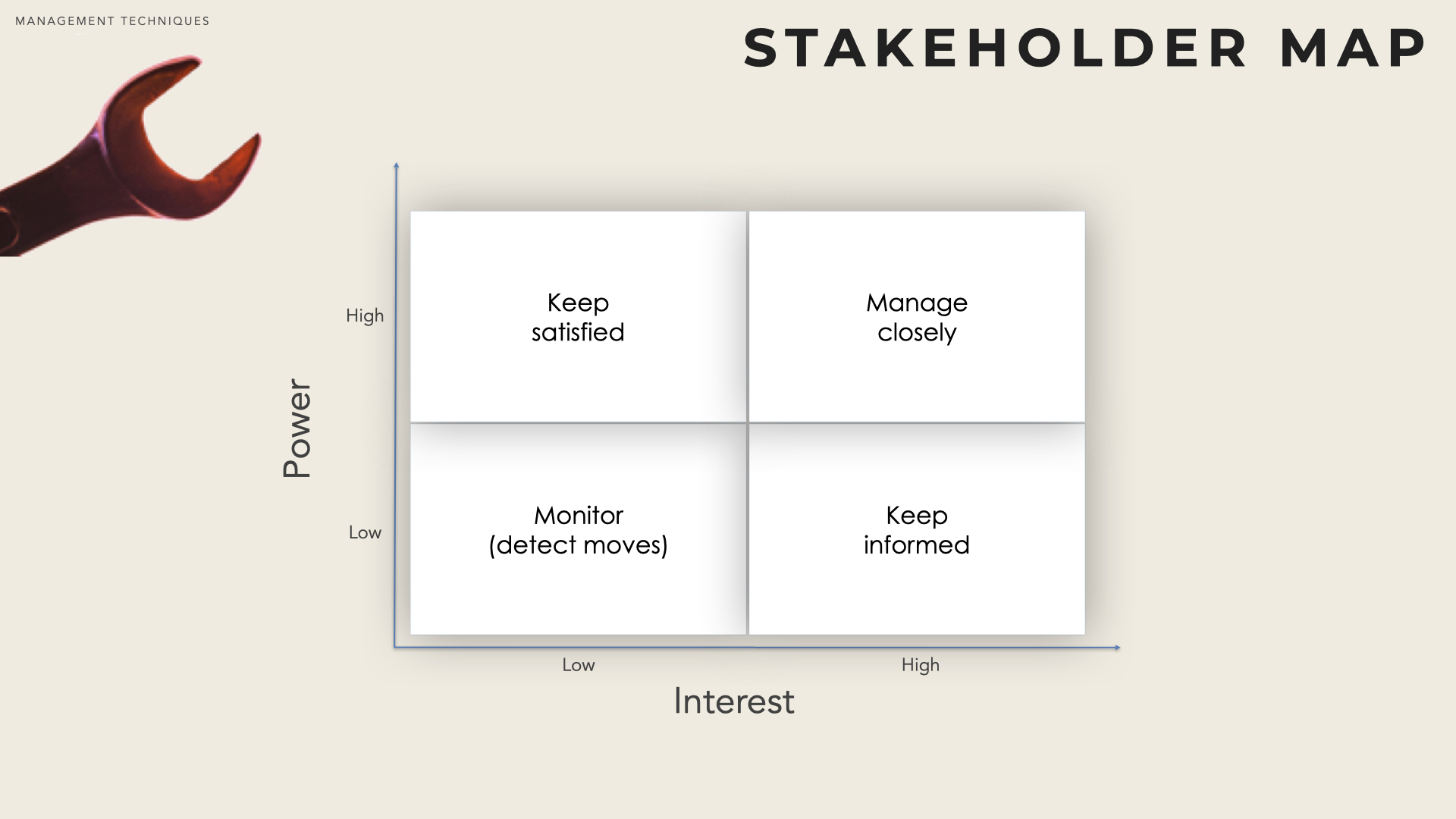

Stakeholder Map

Although various versions of stakeholder maps exist, they are all constructed on similar principles. The objective is to plot a scatter graph and to map the power and expectation of the main stakeholders.

Stakeholders are individuals or groups of individuals who depend on an organisation to fulfil their own goals and whom, in turn, the organisation depends upon.

Stakeholder maps are usually initiated at a very early stage and maintained for the duration of the project. Maps are dynamic by essence as the behaviour / beliefs of the various stakeholders can evolve.

Interest must be understood in its broader sense. A stakeholder who is deeply resisting (for instance because his or her ’comfort zone’ would be threaten) is also considered to have a strong ’interest’. A stakeholder has interest for a project if he/she forms expectations about it, be it for or against the project.

Power doesn’t necessarily correspond to formal authority. Trade unionists, experts, opinion makers can have a lot of power. He who can either facilitate or slow down the implementation of a project, has power. A stakeholder that has power can be in a position to impose his/her expectations or the project. Having power however doesn’t necessarily imply that power must be exercised.

Power represent the ability of individuals or groups of individuals to persuade, induce or coerce others into following certain course of action [Jonhson11].

People in the four quadrants of the matrix must be managed adequately:

Low interest / Low Power - corresponds to people who have little interest in the project and cannot either help or harm. They must be monitored (including in case they would ’move’ to another quadrant) but shouldn’t be bothered with excessive communication or solicitations.

High interest / Low Power - corresponds to people who have interest in the project (either positive or negative) but will be of little help / harm. They must be kept well informed and should be involved at some point (e.g. workshops, interviews) - including when they are not supporting the project. People with a high level of antagonism can be helpful with identifying the risks and drawbacks of the project.

Low interest / High Power - corresponds to people who have little interest in the project (either positive or negative) but have power and there- fore could decide to act for or against the project. They must be kept satisfied, kept informed but not get bored with messages. For those of them who are crucial to the decision-making and/or the strategy implementation, their level of interest (synergy) must be increased and therefore it is key to understand why their current level of interest remains low.

High interest / High Power - corresponds to people who have a lot of interest in the project (either positive or negative) and have power to act for or against the project. They must be fully engaged and satisfied. Among these population it is important to further analyse the level of interest into its two components: synergy & antagonism.