Complements

Ex-post narrative - the Honda Case

The now-famous Honda Case is a perfect illustration of the difference between deliberate and emergent strategies. It also proves that convincing ex-post stories can be built by analysts who try to report and make intelligible the successful strategic moves and/or missed opportunities of firms.

However, it seems that in that case (but in how many more ?) the ex-post explanations had completely reconstructed the initial strategic intends and/or deviate from the hard facts.

The Honda story: the context

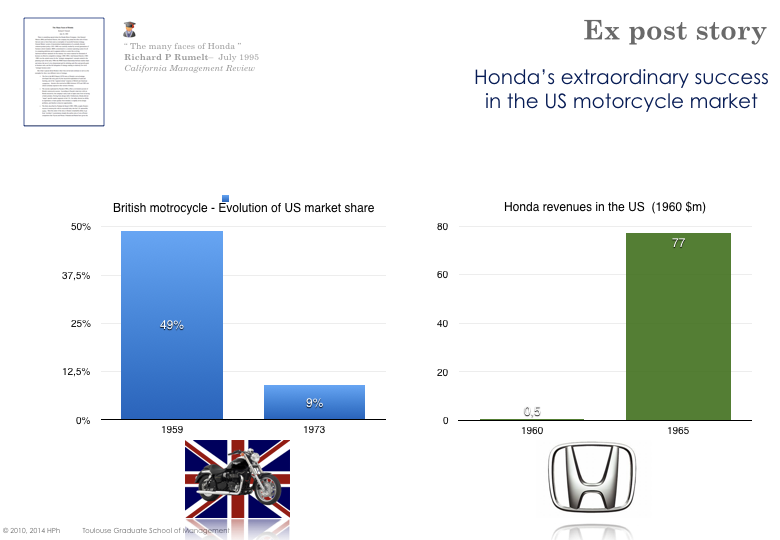

In the ’60s Harley Davidson was the dominant player in the US motorcycle market, followed by British firms (BSA, Triumph, Norton) and Guzzi of Italy. In 1959, the British firms represented 49% of cumulated market shares. However, by 1973 they had felt to 9%, while motorcycle registrations had more than triple over the same period. Meanwhile, Honda’s sales grew from MUS$ 0.5 in 1960 to MUS$ 77 in 1965.

Evolution of the motorcycle industry in the US

Several articles ( [Rumelt95] [Lecrow93] ) examines the various explanations offered by analysts about Honda’s success in the US motorcycle market, in the ’60s.

The BCG Report

In a report ordered in 1975 by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (British secretary of state for Industry), the BCG explains the decline of the British motorcycle industry and suggests strategic alternatives for the future.

Being produced as part of a public contract, the report was openly published by the British government. The two-volume 368-page report still provides the most complete published view of a strategy boutique at work doing industry and competitive analysis.

According to the BCG, Honda’s success finds its roots in cost advantage, the successful exploitation of scale and learning which then lead to what they call the segment retreat response of British and American competitors. Anyone who received an MBA in the ’80s (especially in an Ivy League University) was almost certainly exposed to this version of history.

«The success of the Japanese manufacturer originated with the growth of their domestic market during the 1950s. Indeed, by 1960, the Japanese had developed huge production volumes in motorcycles in their domestic market and volume-related cost reductions had followed » – BCG report, quoted in ( [Lecrow93] ) .

BCG Report about the evolution of the motorcycle industry

Lecrow and Morison stress that Honda decided in 1959 to invest in a plant to manufacture 30000 units per month, well ahead of existing demand at the time. This is, according to the BCG, yet evidence of their strategy of taking a low-cost position.

« The rate of technological learning tends to be related over time to accumulated production experience as the company develops and applies lower-cost methods in the course of conducting its business. […] High volumes per model provide the potential for high productivity as a result of using capital intensive and highly automated techniques. […]

The overall result of this philosophy over time has been that the Japanese have now developed an entrenched and leading position in terms of technology and production methods »

The British found it impossible to match low Japanese price levels on small bikes. Therefore, they responded to the Japanese challenge by withdrawing from the smaller bike segments.

The real Story as it occurred

Richard T. Pascale ( [Pascale84] [Rumelt96] ) offers a revisionist account of Honda’s motorcycle success.

The Honda Case - Interviews of the main protagonists

According to Mr Kawashima ( [Pascale84] ) , who became the first president of American Honda, the small Japanese team arrived in the U.S. with only weak English language skills, and a vague plan to compete with European exports in the 250cc to 300cc size range. Their first attempt was a failure.

We dropped in on motorcycle dealers who treated us discourteously and gave the general impression of being motorcycle enthusiasts who, secondarily, were in business. There were only 3000 motorcycle dealers in the US of which only 1000 were open five days a week. Inventory was poor and manufacturers sold motorcycles to dealers on consignment. The retailers provided consumer financing. After-sales services were not at the expected level. It was discouraging. […]

However as 60000 motorcycles were imported from Europe, it didn’t seem unreasonable to shoot for 10% of the import market. In truth, we had no other strategy than the idea of seeing if we could sell something in the US. […]

We were entirely in the dark the first year. We were not aware the motorcycle business in the US occurs during a seasonable April to August window and our timing coincided with the closing of the 1959 season. Our hard-learned experiences with distributorships in Japan convinced us to try to go to the retailers directs.

By midyear, in 1960, we had 40 retailers and some of our inventory - mostly larger bikes - in their stores. By April 1960, reports were coming that our motorcycles were leaking oil and encountering clutch failure. Honda’s facile reputation was being destroyed before it could be established. Our testing Lab in Japan worked twenty-four-hour a day and within a month a new design was available »

The Honda Case - Ex post Story

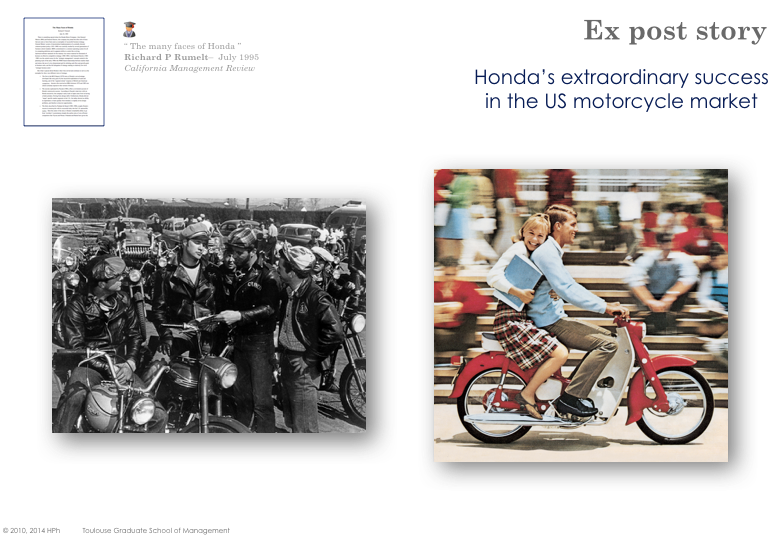

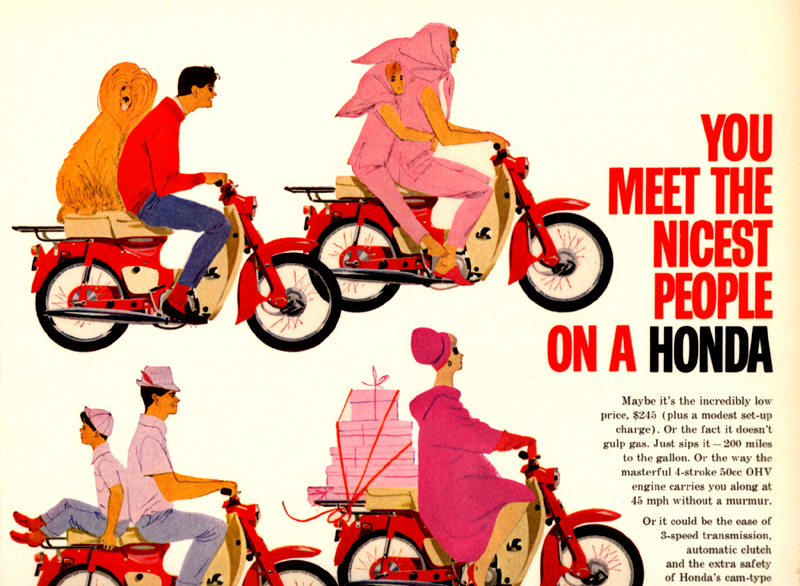

In the early ’60s, motorcycles attracted barely anyone and had grown bad reputation – „the stereotype of the motorcycle by then, was a leather-jacketed, teenage trouble-maker” ([ibidem]). According to the interviews of the management team of Honda America, this is this factor that initially prevented them from offering their 50cc on the American market, although it was already acclaimed in Japan.

We had not attempted to sell our 50cc Supercubs, despite their huge success in Japan. In the US, we thought, the market was expecting bigger and more luxurious machines. However, we used the Honda 50cc ourselves to ride around Los Angeles. They attracted a lot of attention and one day we received a call from a Sears buyer. We took note of Sears’s interest but persisted in our refusal to sell through an intermediary. We still were very hesitant to push the 50cc bikes, out of fear that they might harm our image in a heavily macho market

In the spring of 1963, an undergraduate marketing student at UCLA designed an ad campaign in fulfilment of a course assignment. Lecrow and Morison ( [Lecrow93] ) report that when Grey Advertising (who had acquired the rights from the student) tried to sell the idea, the Honda management team was split on the decision.

Honda, however, adopted the campaign and launched their 50cc on the US market. The ad campaign was featuring clean-cut people with ready smiles, including fashionable women, with a very strong slogan.

As demand grew, the entry team reinvested profits back into the U.S. business. Honda then progressively re-invested all the market segments. In ’Blue Ocean Strategy’ terms, Honda extended the industry boundaries and discovered an untapped market space.

Rather than trying to outperform establish competitors to grab a greater share of existing demand, they managed to create new demand through a new set of product attributes. Building on their solid reputation and brand notoriety, they grew to other segments and started to dominate the market.

Whatever the degree of conviction of an explanation, always seek to objectively analyze the true situation and form a fact-based judgment.

Strategy Goes beyond firms

Strategy deals with long-term goals and value creation. Both terms must be understood in a broad sense. As a result, strategic management is not limited to firms.

This section draws from ( [Grant06] ) .

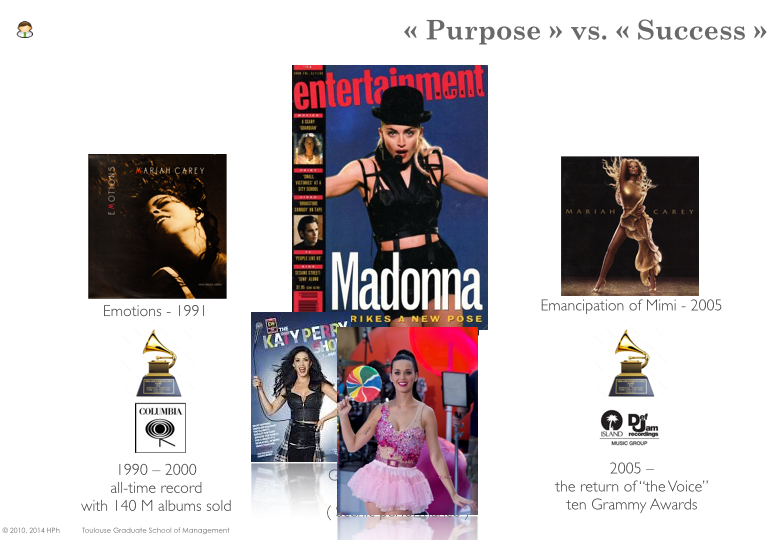

Mariah Carey’s strategic moves

Mariah Carey, an American singer, songwriter and actress, made her debut in 1990 with the release of an eponym studio album: Mariah Carey. The album went multi-platinum and spawned four consecutive number-one singles, on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart. She then continued with a series of hits, all produced by Columbia Records: Emotions (1991), Music Box (1993) and Merry Christmas (1994). Daydream (1995), made music history when the second single, One Sweet Day spent a record sixteen weeks on top of the Billboard Hot 100. It remains the longest-running number-one song in US chart history. From 1990 to 2000 she sold more than 140 million albums, hitting an all-time record [source Wikipedia]. Beyond her indisputable commercial success, Mariah Carey also became a benchmark artist of R&B.

In 2001 she left Columbia Records and signed a record-breaking $100 million five-album recording contract with Virgin Records (EMI Records). She moved away from R&B and introduced more hip-hop into her arrangements. She also started an actress career with Glitter and also signed the soundtrack of the movie. Both the public and media very poorly received her performance, judged disappointing. In 2001 she received the Golden Raspberry Award (Razzie) for Worst Actress.

Grant reports that in 2002, Lyor Cohen (the chief executive of Island Def Jam records) spotted an opportunity:

„I cold-called her and said, I think you are an unbelievable artist and you should hold your head up high. What’s your competitive advantage? A great voice, of course, and what else? You write all songs: you are a great writer. So why did you stray from your competitive advantage? If you have this magnificent voice and write such compelling songs, why are you dressing like that? Why are you using all these collaborations with other artists?”.

In 2005, she launched a new album, returning to her initial R&B style. It debuted atop the charts in several countries and was warmly accepted by critics. The album’s second single, We Belong Together, became a ’career re-defining’ song for Carey, at a point when many critics had considered her career over. Music critics heralded the song as the ’return of The Voice’, After staying at number one for fourteen non-consecutive weeks, the song became the second longest-running number-one song in US chart history and Billboard listed it as the ’song of the decade’ and the ninth most popular song of all time. The album earned ten Grammy Award nominations: eight in 2006 for the original release (the most received by Carey in a single year) and two in 2007 for the Ultra Platinum Edition. In 2006 Carey won Best Contemporary R&B Album for The Emancipation of Mimi as well as Best Female R&B Vocal Performance and Best R&B Song for We Belong Together [source Wikipedia]

There is not ‘One-fit-all’ strategy

Mariah Carey was very successful from 1990 to 2000. From 2000 to 2005 she adopted a ’new strategy’ and became far less successful. When in 2005, she returned to her ’initial strategy’, success came back immediately. One could argue that there is only ’one best way’ to achieve success and any attempt to do otherwise is doomed to failure.

However can you think of singers who have been quite successful by adopting the behaviour that was fatal to M. Carrey?

Strategy Making

„No one has ever seen or touched a strategy ” ( [Mintzberg78] [Mintzberg00] ) . Every strategy is an invention, a creation shared by the members of an organisation, through their intentions and by their actions.

A major issue of strategy formulation becomes, therefore, to understand how intentions diffuse through an organisation to become shared and how actions come to be exercised on a collective, yet consistent, basis.

As a process Strategy is not linear and not limited to its economics perspective. It also encompasses sociological aspects: the people side of managing strategy implementation.

Strategy formation

A large body of literature addresses the question of how organisations make significant decisions. Henry Mintzberg distinguishes three main theoretical modes:

Planning Mode - (by far the largest body of published materials) depicts a highly ordered process: strategies are explicitly and intentionally produced and formulated by a purposeful organisation.

Adaptative Mode - in contrast, portrays the process as one in which many decision-makers (sometimes with conflicting goals) bargain among themselves to produce a stream of incremental, disjoint decisions.

Entrepreneurial Mode - corresponds to a situation where a powerful leader takes bold, risky decisions toward his vision of the future of the organisation.

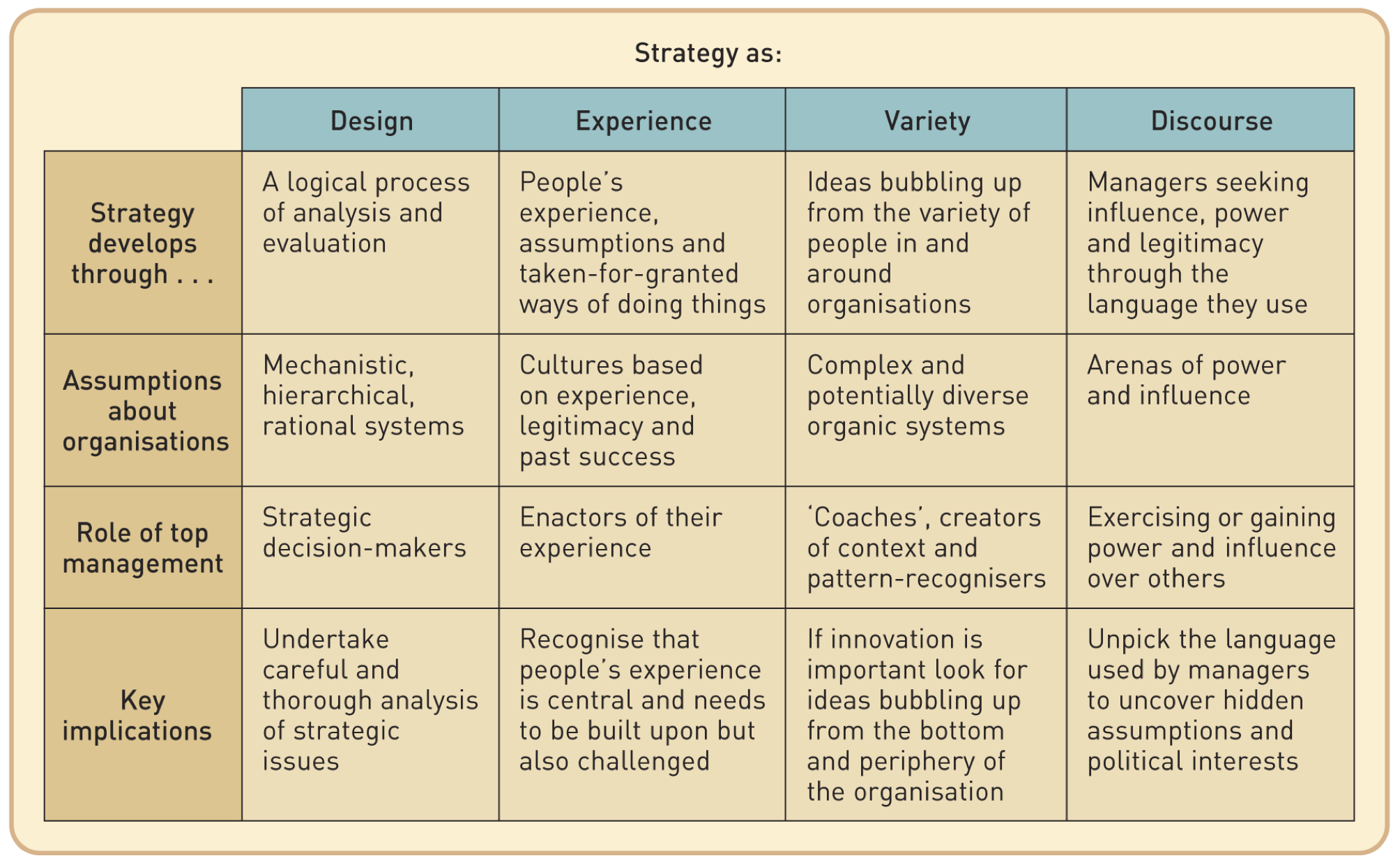

Strategy Lenses

A more recent analysis ( [Johnson11] ) proposes four different perspectives (or lenses). Each approach brings its own perception bias but also specific insight.

Strategy as Design - assumes that a comprehensive strategy blueprint can be established before any implementation starts (see planning mode above). Therefore, it puts a lot of emphasis on analysing and planning. Reacting quickly to unpredictable events is nearly excluded. Strategy formulation is systematic, linear and logic-driven. It underplays the political aspects of human organisations.

Strategy as Experience - considers that the future strategy must draw on the experience of the organisation and its managers. Decisions are based on less clear-cut analyses and often result from negotiated compromise. Radical change is unlikely to occur.

Strategy as Variety - focuses on fostering the emergence of disruptive ideas. It promotes diversity (e.g. opens the strategy debate to a vast variety of people within and without the organisation) and idea generation.

Strategy as Discourse - underpins power games among decision-makers and politics.

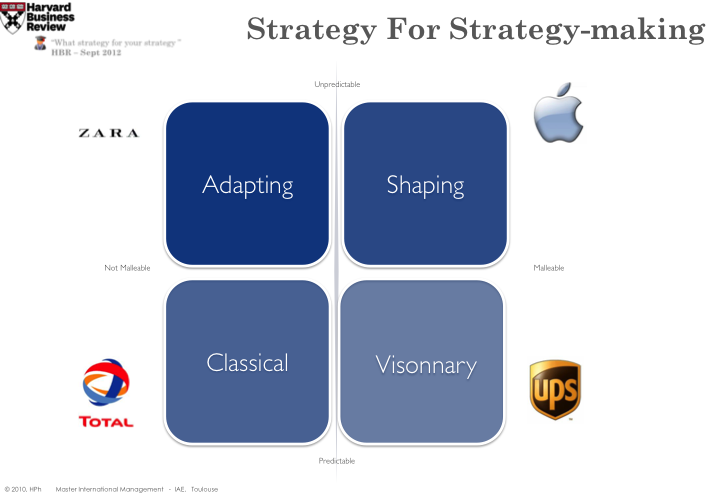

What Strategy for your Strategy

Predictability is not comparable in the oil industry and the Internet software industry. From this obvious observation, M Reeves, C. Love and Ph Tillmans Reeves et al. ( [Reeves12] ) derive that companies in very dissimilar competitive environment should be planning and developing their strategies in different ways.

Strategy-Making must match competitive environment nature

The oil industry holds few surprises for planners: factors are well identified and outside any single company’s control, barriers to entry are very high, no one is really in a position to change the game. In game theory terms, the oil industry is a game in complete information. By contrast, the Internet software industry is characterised by new firms suddenly popping up from nowhere. The basis of competition can be fundamentally altered without much warning. In such an environment, competitive advantage comes from reading and responding to signals faster than your rivals.

The strategy-making process should match the nature of the competitive environment. Obviously, many factors play into strategy formulation, however, two characteristics are of prime importance: predictability and malleability.

Predictability: measures how far in the future and how accurately you can confidently forecast (e.g. demand, performance, competition dynamics, etc..).

Malleability: measures to what extent you (and your competitors) can influence the industry and market.

These two characteristics delineate four perspectives each corresponding to its own specific strategy-making strategy.

Four Strategy-making strategies

Classical - little malleability, good predictability - The influencing factors of the industry you operate in are well known and identified, the competitive environment is very stable. However, you barely can change the environment (e.g. due to the atomicity of each firm). The canonical strategy formulation process, as taught in business schools, assumes this very competitive environment. Without big surprise, most strategy-making frameworks are designed for such a ’classical’ competitive environment. Within the classical perspective, a company sets a goal, capitalising from its capabilities and tries to fortify that position. Strategy aims at optimising long-term returns and careful planning feeds multi-annual forecasts. Strategy planning hinges upon specific skills and competences – both analytic and quantitative – and usually will be carried out by a dedicated, stand-alone department.

Adapting - little malleability, very unpredictability - A carefully crafted ’classical’ strategy can become obsolete within months or weeks. In such volatile competitive environment, flexibility and the capability to refine/revise plans and targets is what makes the difference. Strategy formulation must then become more agile and experimental. The best bet is to constantly and quickly, produce, rollout and test a variety of products. For instance, ZARA, the Spanish retailer, can design, manufacture and ship new products in less than two weeks. Zara assesses market reaction with small batches and if they prove a hit then ramp-up production. Operations (the capability to quickly react and adapt) is the key success factor when a company is confronted with such a competitive environment. Strategists can no longer work in isolation and on the contrary, must be tightly linked with (or embedded into) operations.

Shaping - a lot of malleability, very unpredictability - this typically corresponds to new, high growth industries with low barriers to entry / high rate of innovations. Demand is very hard to predict and the course of the industry can shift radically. A mature but very fragmented industry can also become a shaping environment. The strategy here consists in not trying to plan or adapt (follow) but in trying to shape the unpredictable so that it benefits to the company whatever turns out: „The best way to predict the future is to invent it” (John Scully, Chairman, Apple Computer). A typical approach is to build a complete ecosystem of customers, suppliers, complementors; to create a platform and to set standards and practices.

Visionary - a lot of malleability, very predictability - sometimes not only can the future be predicted and forecast, but a single company have the power to shape the future. A visionary strategy considers that the environment can be modelled and distorted to its benefit. In 1994, UPS realised that the rising of e-business and online retailers would drive unprecedented demand for delivery services. UPS had the vision, the means and the will to make the necessary investment ($1 billion a year during several years) and to become what they later called the enablers of global e-commerce. UPS integrated its core package-tracking operations with those of web providers and expanded its global delivery capacity through acquisition. By 2000 UPS had captured more than 60% of the e-commerce delivery market.

Thing [Long & Hard] before you choose

A team of researchers ( [Lafley12] ) has been wondering why does strategic planning consume so many resources and so much time while having so little impact?.

This would be, according to them, mainly due to strategic planning only faking scientific approach despite apparent rigour and extensive analysis. Therefore they suggest one could escape this pitfall through a seven-step decision process that systematically scans well-articulated possibilities to ensure that different options are looked at, explored and probed, before any choice is made.

Step1: Frame a choice

Conventional strategy planning starts from the issue to be solved (i.e. decreasing revenues) which drives a strong tendency to get very emotional and to invest in analysing the issues rather than working out solutions. By contrast, the approach should consist in framing the problem as a ’choice’ (for instance by defining mutually exclusive options that could resolve the issue in question). This framing helps strategists conduct stronger analyses and the managers internalise what is truly at stake.

In the ‘90s, Procter & Gamble was eager to become a major player in the global beauty care sector (their objective), still, they only controlled small, down-market brands (e.g. Oil of Olay) and only addressing an ageing consumer base. Rather than dwelling too much on this weakness, Procter & Gamble formulated two options:

dramatically transform ’Oil of Olay’ into something comparable to L’Oréal, Clarins, etc,

spend billions into acquiring an existing skin care brand

Step2: Generate strategic possibilities

Once options are identified, the second step consists in constructing strategic possibilities (including genuinely new ones). A possibility is a ’story’ that describes how a firm might success [how the option can materialize]. It needs to be consistent and ’valid’, however, it doesn’t need to be proved at that stage. Any possibility must explicit

the advantage it aims to achieve or leverage,

the scope across which the advantage applies,

the activities throughout the value chain that would deliver the intended advantage.

This step should involve a team of people from different backgrounds and expertise while trying to avoid as much as possible people emotionally bond to the ’Status Quo’. Operational managers should take part in the complete exercise, as when planners are different from doers then what gets done is different from what gets planned. Several techniques can be mobilised to work out possibilities:

inside-out possibility generation – start with assets and capabilities and reason outward: what does this company do especially well that parts of the market might value and that might produce some profit?

outside-in possibility generation – what are the underserved needs? What are the needs that customers find hard to serve?

far-outside-in possibility generation - what would it take to become the Google, the Apple or the WallMart of this market?

A good set of possibilities must contain at least one possibility that directly questions the status quo (while being considered as feasible and bringing some interest) and at least one possibility that is far enough from the status quo (even if it is not sure it could be doable and/or safe at all).

Step3: Specify the conditions for success

In practice, this step should make explicit the conditions that need to hold true for the possibilities (identified in step 2) to be a success. This is achieved through producing declarative statements such as for possibility P to succeed, condition X must be true. Where typical conditions encompass: the industry structure, the strategic segments, consumer structure and volume, distribution channel, capabilities, costs, competitors’ likely reactions. (for instance ’Channel partners will support us’).

When the list of conditions is established, it should be screened again to eliminate all the nice to have conditions while keeping the must-have.

At that stage, one should refrain from being judgmental and/or expressing their opinions about whether a condition is true or not. The only question is whether or not one would advocate for this possibility, provided that all the conditions were true.

Step4: Identify barriers to choice

Once conditions are identified, one must determine which are more likely to hold. Typically one would ask each teammate to raise their concerns and to rank the conditions by likelihood. More often than not there will be a consensus on most conditions (either that they hold true or that they don’t).

However, the group may have contrasted opinions on a few conditions. Pay close attention to these conditions and also on the people who are the most sceptical: they will be the biggest barriers (potentially a valid obstacle in case of problematic possibilities).

Step5: Design test for barrier conditions

Once the key barriers have been identified they must be tested to determine whether they can hold true or not. Several techniques can be mobilised: survey, data crunching and interviews.

The teammate who is the most reluctant about a given condition should design and lead the test for that condition, as this person will have the highest standard of proof.

Step6: Conduct the tests

At that stage, all the conditions must be checked according to the test protocols defined at step 5. Probing the conditions in the reverse order of confidence (the lazy’s man approach to choice)often turns out to be the most efficient. Indeed as soon as a condition appears to be false, the associated possibility can be eliminated (and there is no need to further test the conditions that are a prerequisite to that possibility only).

Step7: Make the choice

With the possibilities based approach, making the final decision – that is deciding the strategy – only requires choosing the possibility that remains when all barriers have been identified and tested.