The Nature of Strategy ?

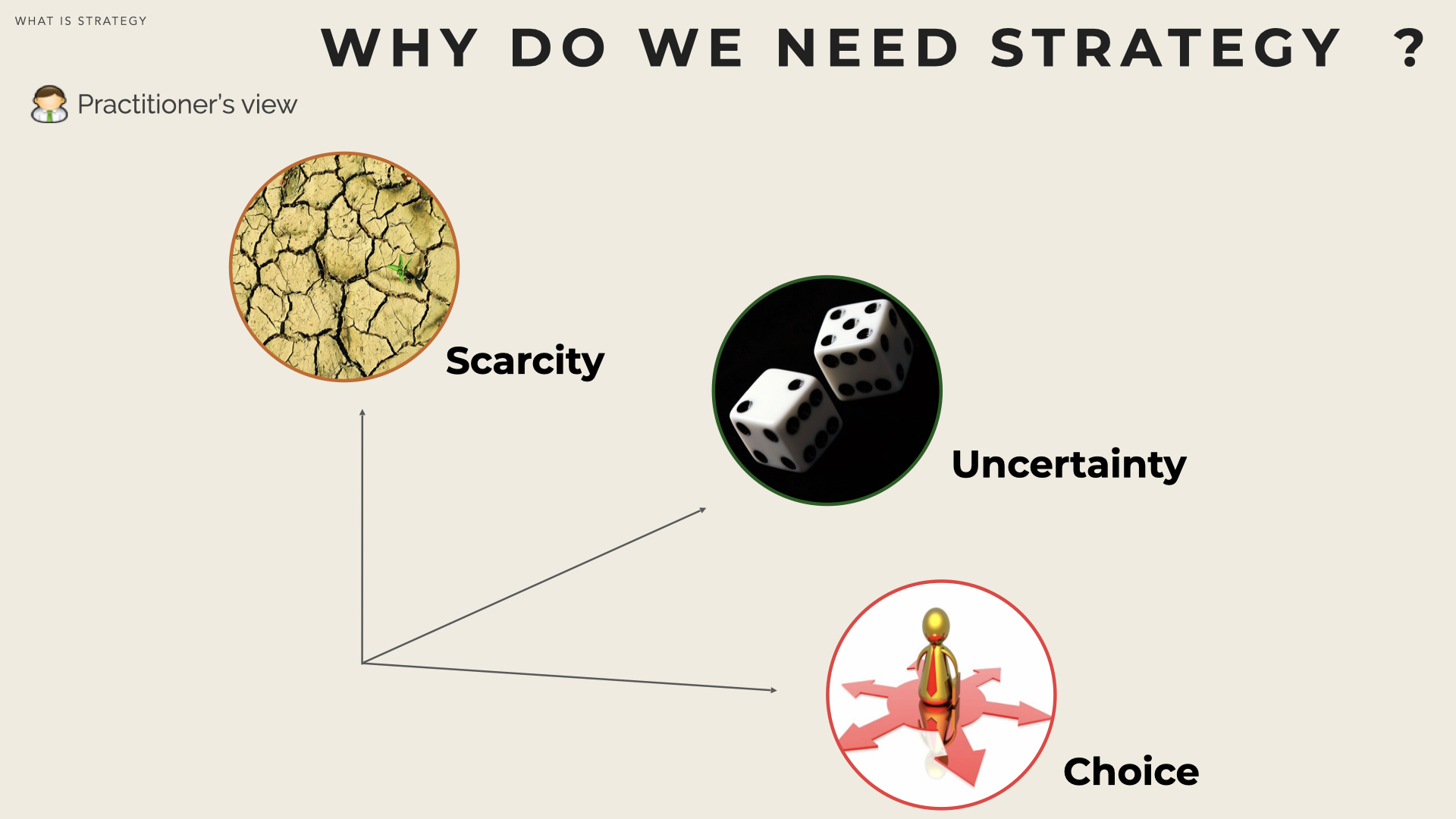

Why do we need Strategy?

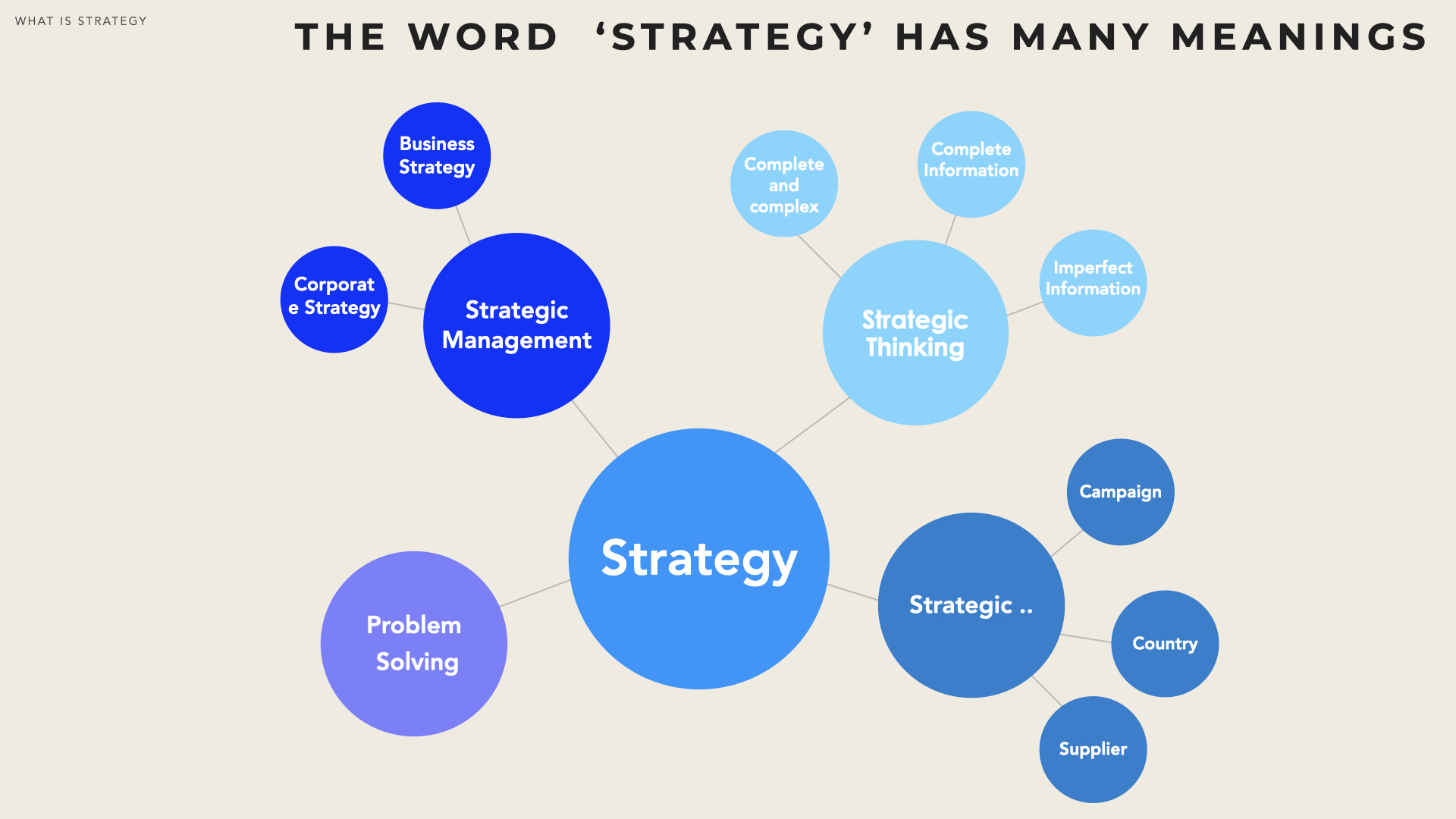

While the overall field of strategic management is rather well delineated, there is very little consensus on What is strategy.

There are strongly differing opinions on most key issues - and disagreements among practitioners, researchers and theorists as to what is strategy - so deep that even a common definition of the term strategy is illusive ( [DeWit10] )

So even before trying to define WHAT strategy is (at that stage let’s consider that strategy conveys the idea of being successful ), let’s first wonder WHY do we need strategy at all

Three major factors underpin strategy

By and large, three major factors underpin the need for strategic management :

Scarcity - without limitation (of resources, skills, demand, competence, time, …) there would be no competition, no struggle to succeed, to control and access knowhow, markets or supply chains. Without scarcity all players could be equally successful, without effort

Uncertainty – firms are exposed to dynamic ecosystems (customers, suppliers, competitors, society, authorities). Things change, often unpredictably. Risk is also inherent to most strategic moves and success can never be taken for granted. In addition, when a player initiates a strategic move, the actual outcome usually also depends upon other players’ reaction, which is rarely easy to forecast. Conversely, existing or to-be competitors may also make anticipated moves, which usually trigger chain responses.

Choice – firms have to make decisions about their long-term orientations. It is usually important to explore several options, probing each one carefully before making a choice. But it is even more important to do make a choice. A firm has no real strategy until it has crossed the Rubicon and made irreversible decisions: select their perimeter of activities (what to do and what not to do), their operating model (how to do it) while preparing their future (e.g. innovation), commit to and execute a course of action. “Focus and commits a significant portion of its resources to the expected outcomes”. ( [Andrews87] )

A situation where no limitation can be spotted, everything seems deterministically planned and no specific decision is expected, should be considered with care. It may be the sign that either it does not fall within the scope of strategic management or it requires some serious reassessment.

A real strategy involves a clear set of choices that define what the firm is going to do and what it’s not going to do. Many strategies fail to get implemented, despite the ample efforts of hard-working people, because they do not represent a set of clear choices.

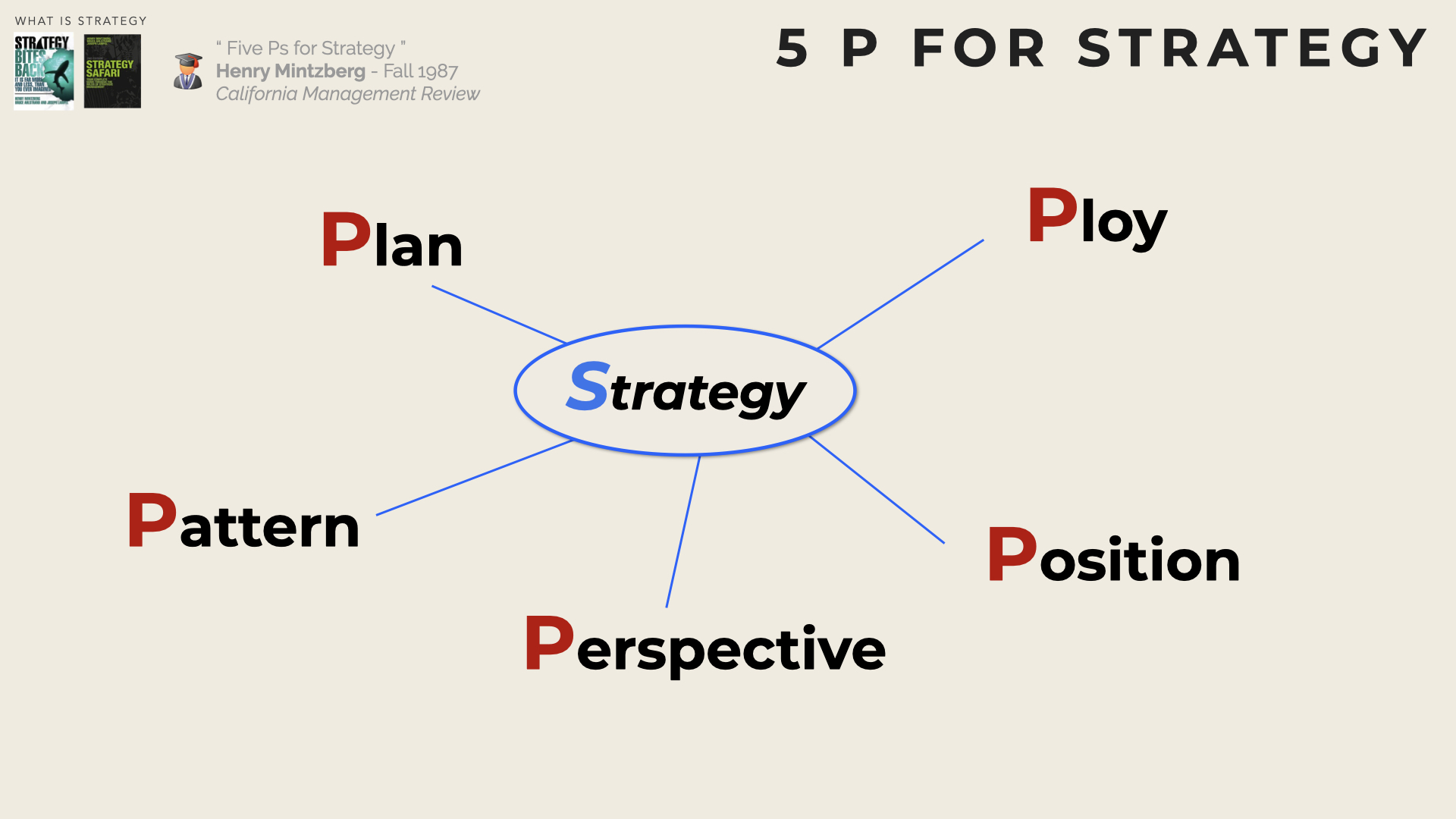

The 5P for Strategy

In a seminal work, Henry Mintzberg ( [Mintzberg87] [Mintzberg98] [Mintzberg05] ) stresses that the word strategy is being used in five different ways, in the field of strategic management, even if it is traditionally defined formally only in one.

Strategy as a Plan

Considered as a plan, strategy is some sort of consciously intended course of action, a guideline (or set of guidelines) to deal with a situation. By this definition, plans have two essential characteristics: they are made in advance of the actions to which they apply and are developed purposefully.

As a plan, a strategy is formulated through a conscious process and can be stated explicitly and formally. To Drucker ( [Druker85] ) strategy is purposeful action.

In Game Theory ( [VNM44] [Polak07] [Dixit15] [Aumann92] ) Strategy is as well a complete algorithm for playing the game. A Strategy tells a player what to do for every possible situation throughout the game.

Plans enable commitment to a course of actions and coordinate all initiatives into a single cohesive pattern. Plans also facilitate optimal resource allocation and are good means of programming activities in advance. ( [DeWit10] )

Strategy as a Ploy

‘Strategy’ can as well correspond to a specific manoeuvre intended to outwit an opponent. A firm may, for instance, pretend to establish a new practice area to discourage a competitor to do so. Here the real strategy (the real intention) is to prevent the move from the competitors and not the new practice area itself.

Getting the better of competitors, by plotting to disrupt, dissuade, discourage, or otherwise influence them, can be part of a strategy.

Strategy as Patterns

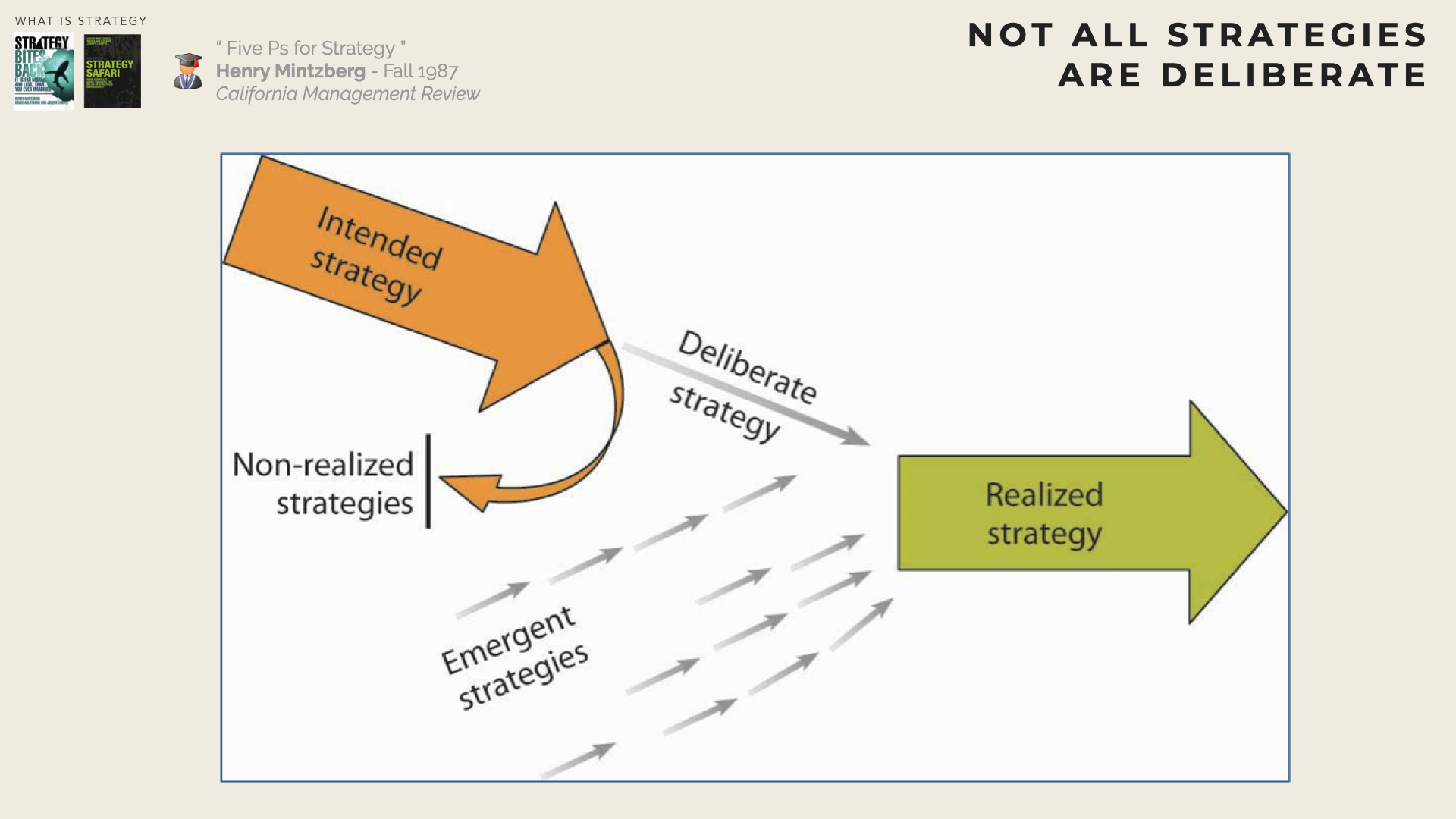

A strategy will be considered to have formed when a sequence of decisions exhibit some consistency over time. While Strategy as a plan and Strategy as a ploy are always indented, Strategy as a pattern is not necessarily planned neither foreseen in advance.

Strategy as patterns – i.e. a stream of actions, consistency in behaviour – can be compared to periods of great artists (i.e. their decisions about their work), where certain consistencies in their use of colours, forms, etc. can be observed (e.g. Picasso’s blue period). Strategy, in that case, corresponds to a posteriori consistencies in decisional behaviour (whether intended or not).

As stressed by the Open University ( [OpenU] ) “ every time a journalist imputes a strategy to a corporation or to a government, and every time a manager does the same thing to a competitor or even to the senior management of his own firm, they are implicitly defining strategy as pattern in action– that is, inferring consistency in behaviour and labelling it strategy. They may, of course, go further and impute intention to that consistency – that is, assume there is a plan behind the pattern. But that is an assumption, which may prove false ”.

Strategy formulation is the conscious process through which an intended strategy is articulated. However, a strategy may also form gradually perhaps unintentionally, as decisions are made one by one.

In other words, strategies are not always deliberately planned. Strategy can be intended (a pattern of decision that formulates a course of action beforehand) or realized (a pattern of actions which forms without being explicitly formulated).

Strategy as Position

Strategy can consist in a position, i.e. a match (sometimes mismatched) between the internal organisation and its external environment.

“Position is a static concept. At a given moment in time, is the firm competing on the basis of low costs or because it is differentiated in key dimensions”. ( [Besanko13] )

In management terms, strategy becomes a product-market domain where resources are concentrated. Strategy as position is what a firm do or don’t do (which is different from the plan, i.e. the course of actions to achieve it). A position can be preselected and aspired to through a plan (or ploy) and/or it can be reached, perhaps even found, through a pattern of behaviour.

In economic terms, a position generates a rent (returns for being in a unique place). “Strategy is creating situations for economic rents and finding ways to sustain them” ( [Rumelt82] )

Strategy as position must not be limited to ’two-person games’ (head-on competition), or even n-person situations. Strategy as position applies to any viable position, whether or not directly competitive.

Strategy as Perspective

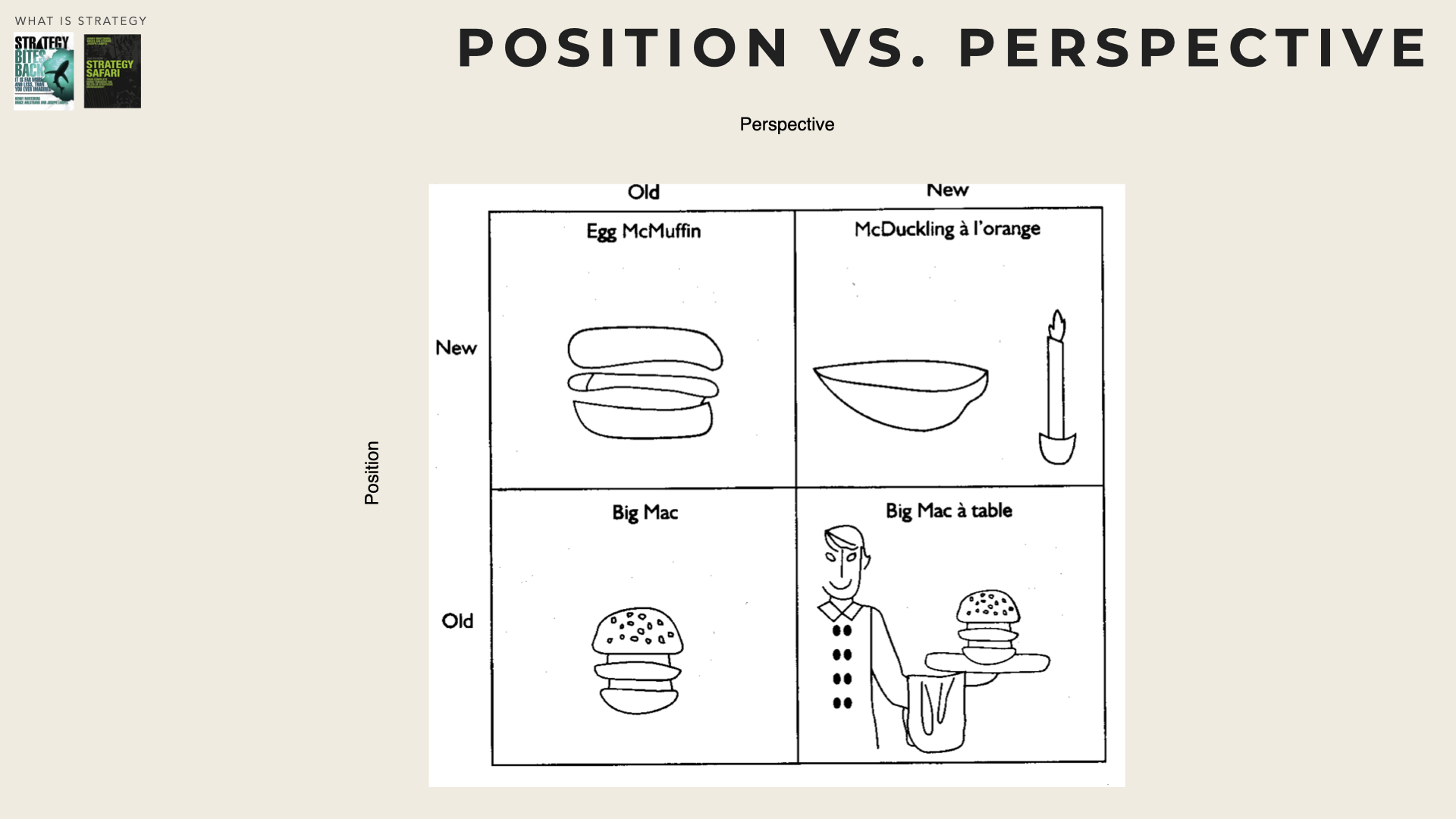

Strategy can be a perspective, its content consisting not just of a chosen position, but also of an ingrained way of perceiving the world that usually echoes the deepest firm’s beliefs and values. Some organisations are aggressive pacesetters, creating new technologies and exploiting new markets, other perceive the world as set and stable, sit back in long-established markets and build protective shells around themselves, relying more on political influence than economic efficiency. There are organisations that favour marketing and build a whole ideology around that (e.g. IBM) others treat engineering in this way (e.g. Hewlett Packard) and then there are those that concentrate on sheer productive efficiency (e.g. MacDonald’s).

The above example, borrowed from ( [Mintzberg98] ) illustrates the difference and complementarity between strategy as a position and strategy as a perspective. McDonalds can focus on hamburger for lunch and diner or diversify into sandwiches for breakfast (they did in the late ’90s). However, McDonalds can continue to see itself as a fast food and value speed or want to conceive itself as a more sophisticated restaurant (with tablecloth, candles, china and silver cutlery).

What does Strategy mean?

“Strategy” in everyday conversations

In everyday conversations, the word strategy far exceeds the domain of strategic management. Considering just a glimpse of the many different meanings, at least three specific contexts can be stressed, in addition to strategic management: strategic thinking, problem-solving and important things.

- Strategy for Important it is very common to hear about strategic customers, strategic suppliers, strategic country, strategic campaign, strategic project, etc. More often than not, the adjective ‘strategic’ stands here for ‘important’ and unless evidence of scarcity, uncertainty or decision can be found (see herebelow), such situations have only very remote resemblance with strategic management.

‘Strategic customer’ must usually be understood as ‘important customer’, except maybe if the customer is an opinion leader for the industry that can influence other customers and change the game.

- Strategy for Problem Solving the word ‘strategy’ is also commonly used to mean way to solve a problem (i.e. ‘a plan’ or what behavioural scientists and computer scientists call a ‘heuristic’).

In the above example, ‘Strategies for organising items in the garage’ sounds great but must be a bit remote from ‘Strategic Management’ .

Strategic Management

Strategic Management (formerly ‘Business Policy’) is a rather young academic field that intersects with several other domains such as economics, sociology, marketing, finance and psychology. ( [Nag07] )

Interest for Strategic Management started in the ‘50s with influential scholars such as Peter Drucker , Alfred Chandler or Igor Ansoff . Very soon the development of Strategy continued with very practical considerations, in particular with the emergence of Management Consulting boutiques, such as the Boston Consulting Group founded by Bruce Henderson in 1963.

The business practice, as well as academic field, were renamed in the early ‘80s as Strategic Management after Schendel and Hofer’s book “Strategic Management: A New View of Business Policy and Planning”.

Strategic Management is the pattern of decisions in a company that determines and reveals its objectives, purposes or goals, produces the principal policies and plans for achieving those goals, and defines the range of business the company is to pursue, the kind of economic and human organisation it is or intends to be, and the nature of the economic and non-economic contribution it intends to make to its shareholders, employees, customers and communities [Andrews 87]

Broadly speaking, Strategy Management can be divided into two aspects: ‘Business Strategy’ and ‘Corporate Strategy’.

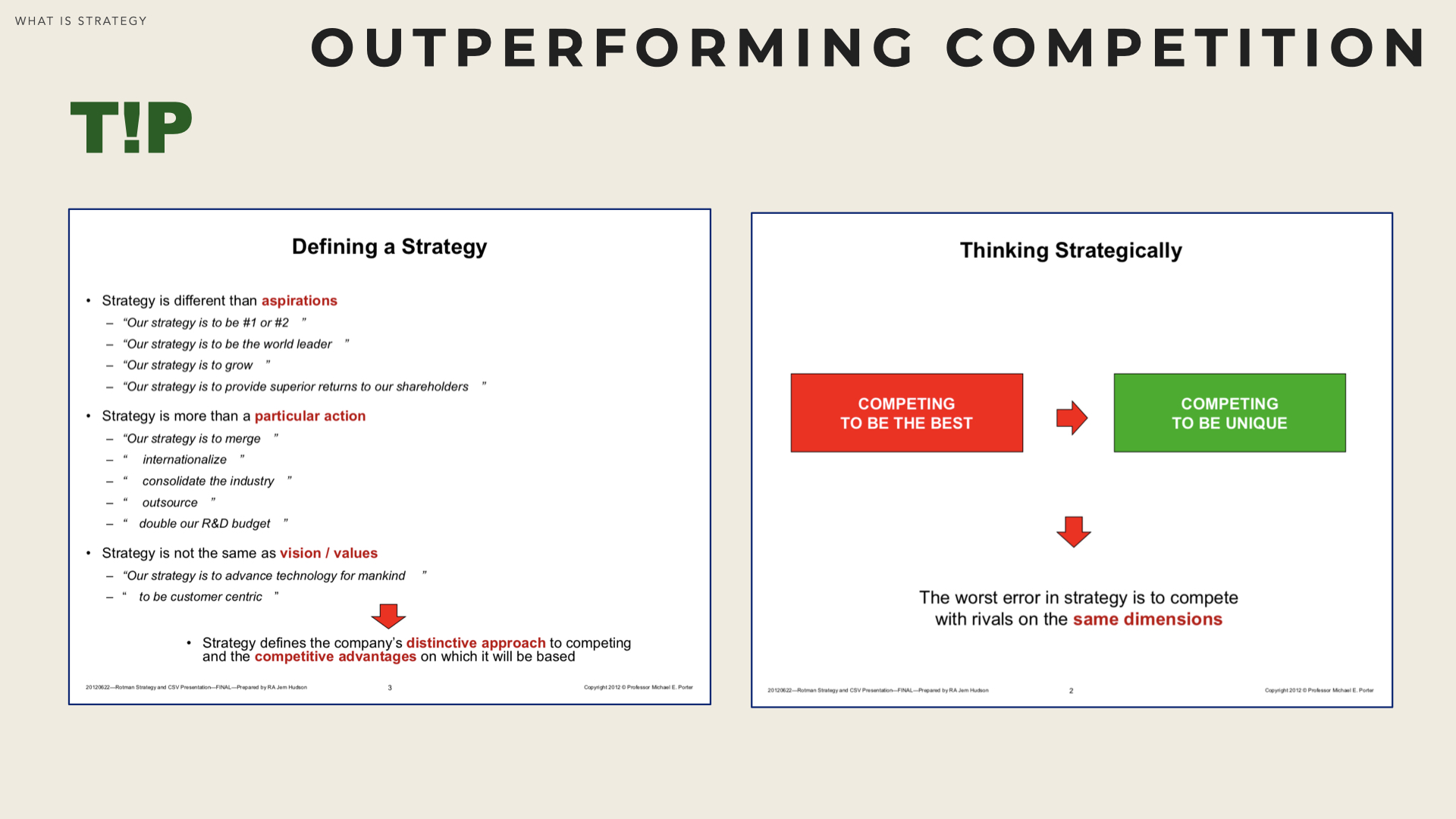

Business Strategy addresses the question of How to be successful in individual markets, for each business unit. It focuses on how to compete (as well as on how to avoid competition).

Business strategy is the determination of how a company will compete in a given business and position itself among its competitors. ( [Andrews87] )

Corporate Strategy applies to firms that own several businesses. The central question of Corporate Strategy is “how a collection of businesses owned by a single firm, creates more value than the sum of its parts”. It deals with clarifying how the mother company provides support to its business units and increases the total value.

Corporate Strategy refers to the strategy that multi-business corporations use to compete as a collection of multiple businesses. ( [Puranam16] )

Strategic decisions are complex problems

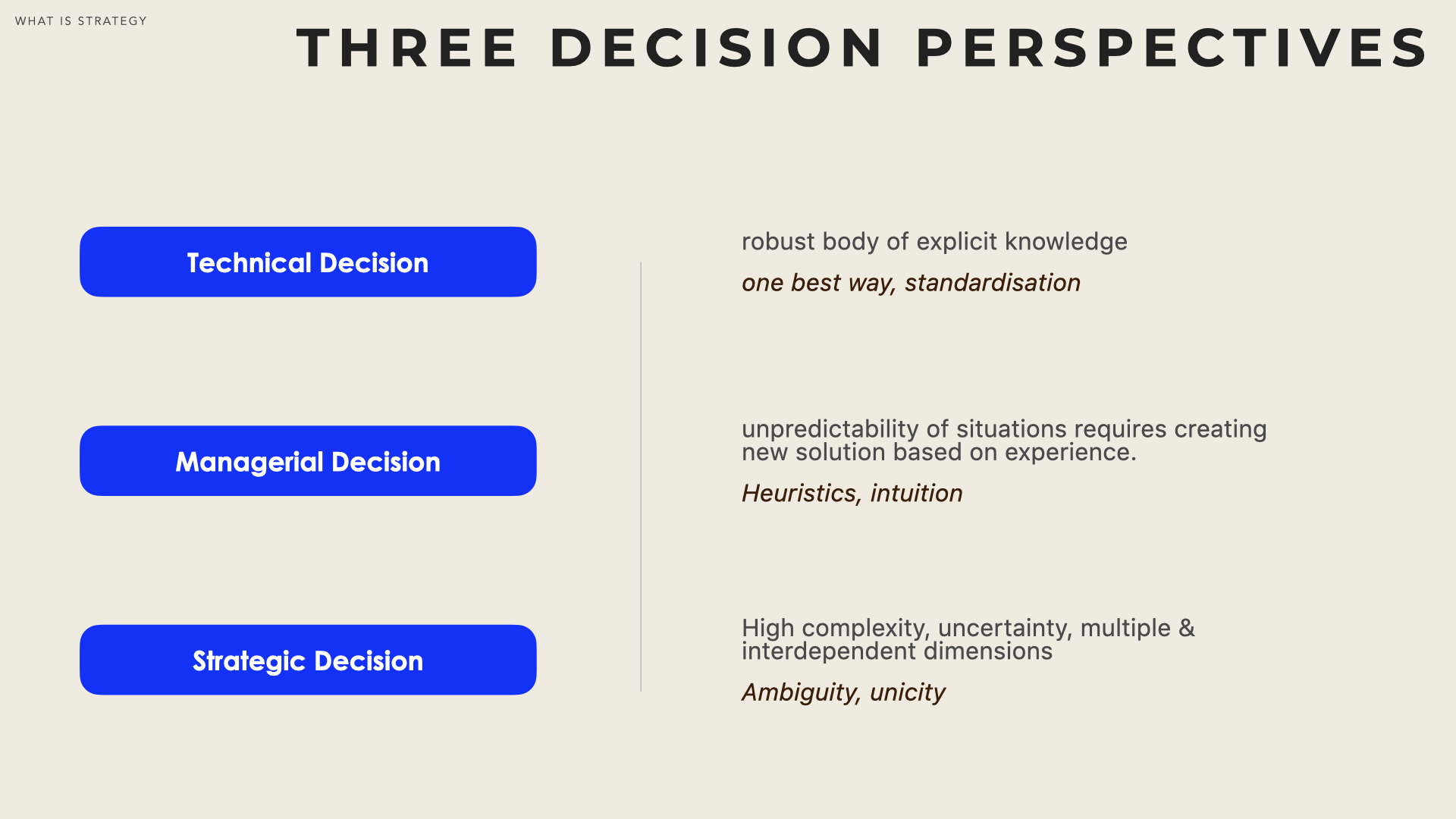

As underlined in ( [Robertson] ) social science has identified three different levels of decisions in organisations.

Technical decisions (including operating procedures) are supported by a strong and explicit body of knowledge, and correspond to situations where a solution can be derived given certain premises.

Managerial Decisions deal with situations where complexity is such that it cannot be sorted as a technical problem and shortcuts based on experience and heuristics (aka rules of thumb) must be taken.

Strategic decisions concern situations characterized by their high complexity, (they relate to problems with multiple and related dimensions) and their high uncertainty (they are characterized by the interdependent behaviour of different actors).

A critical task of upper-level management involves the identification and structuring of the most important problems threatening the organization’s ability to survive and adapt in the future.

Strategy doesn’t address the everyday, routine problems but the problems and issues that are unique, important and frequently ambiguous [McCaskey, 1982]

Strategic problems are wicked problems ( [Mason81] ) characterised by their interconnectedness to other problems, their complexity, and their uncertainty in a dynamic environment. Any strategic problem is highly dependent on its environment (including moral and societal aspects), requires to merge various viewpoints (often ambiguous, contradictory or even conflicting) and will end-up in difficult trade-offs of alternative options.

Tools and Problem-solving perspectives

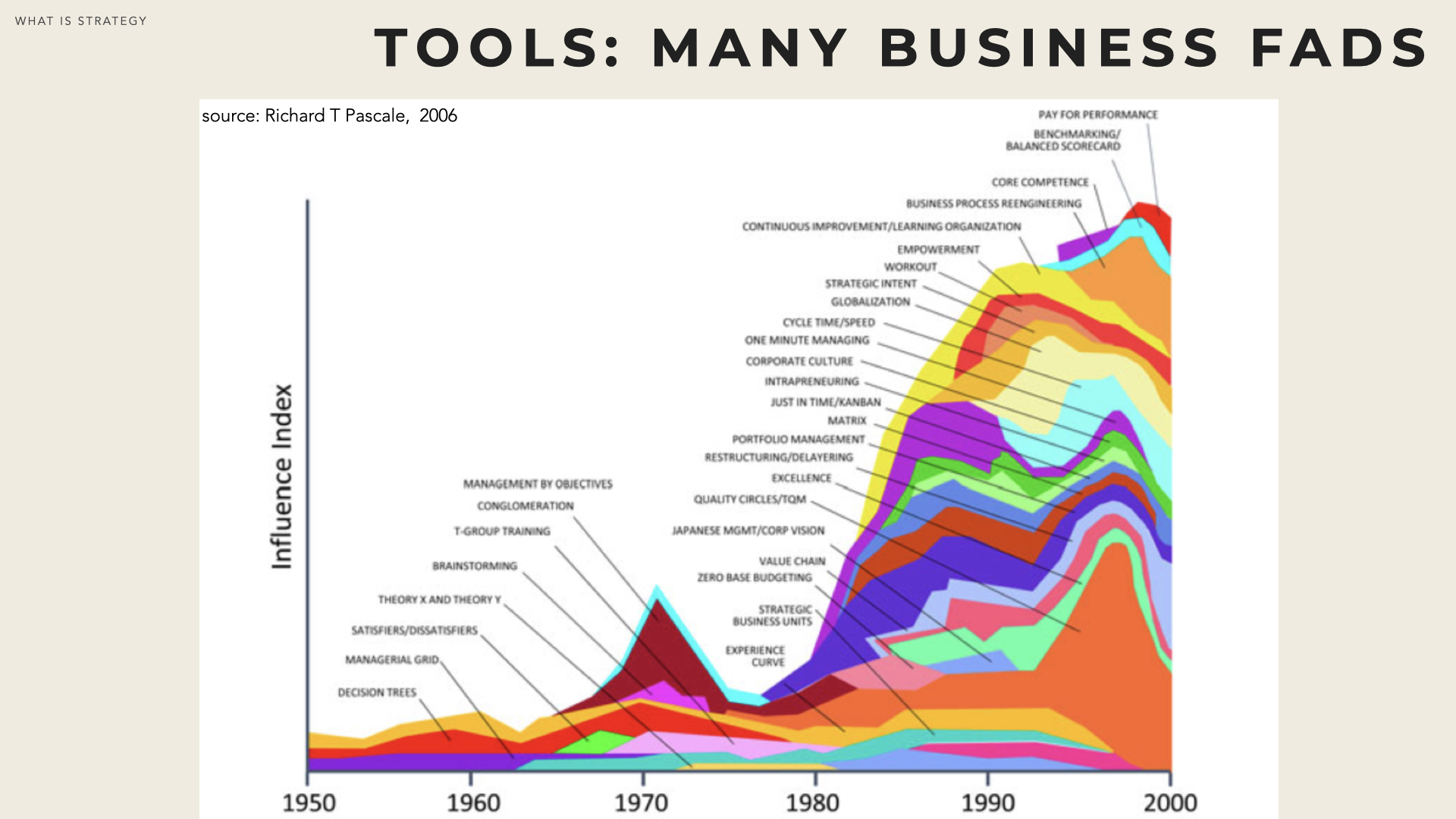

The first MBA program was created at Harvard in 1908. Since then, management literature has built up and many management tools (or Business Fads as Richard Pascale of the Saïd Oxford Business School, calls them) have developed. Temptation can be high to predominantly focus on tools under the expectation that ‘they can solve it all ’.

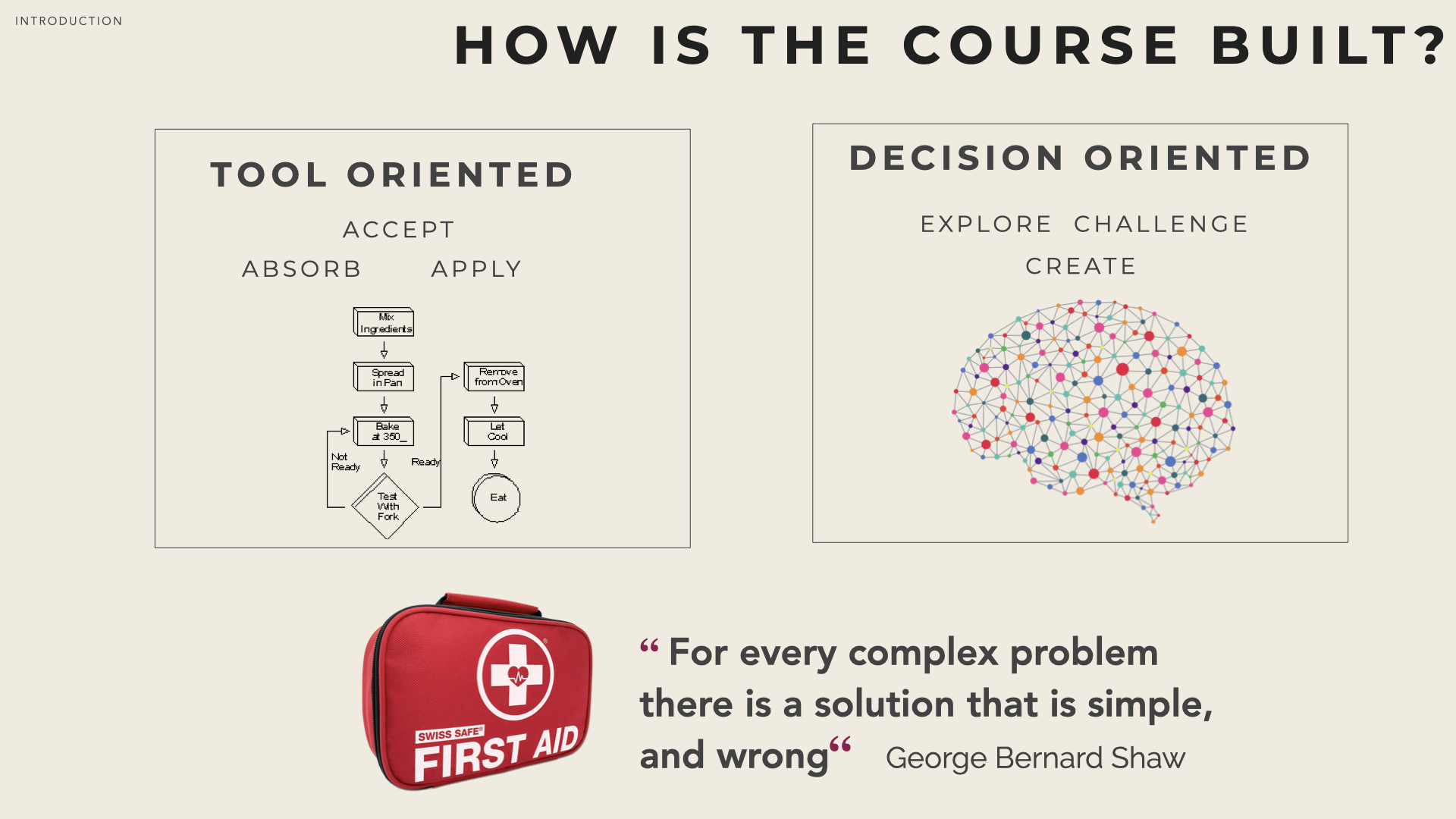

As stressed by B. De Wit & Ron Meyer ( [DeWit10] ) “Strategy” can be considered from either a tool perspective or a problem-driven perspective. With the tool approach, the focus is on understanding and learning the various instruments that can be mobilised. By contrast, the problem-driven approach first addresses what is at stake, without initially considering how to solve it.

There is no “silver bullet” for strategizing and therefore, in these pages, we seek to adopt the problem-solving perspective: understanding the problem comes first and looking for available tools to solve it comes next.

Bad Strategies

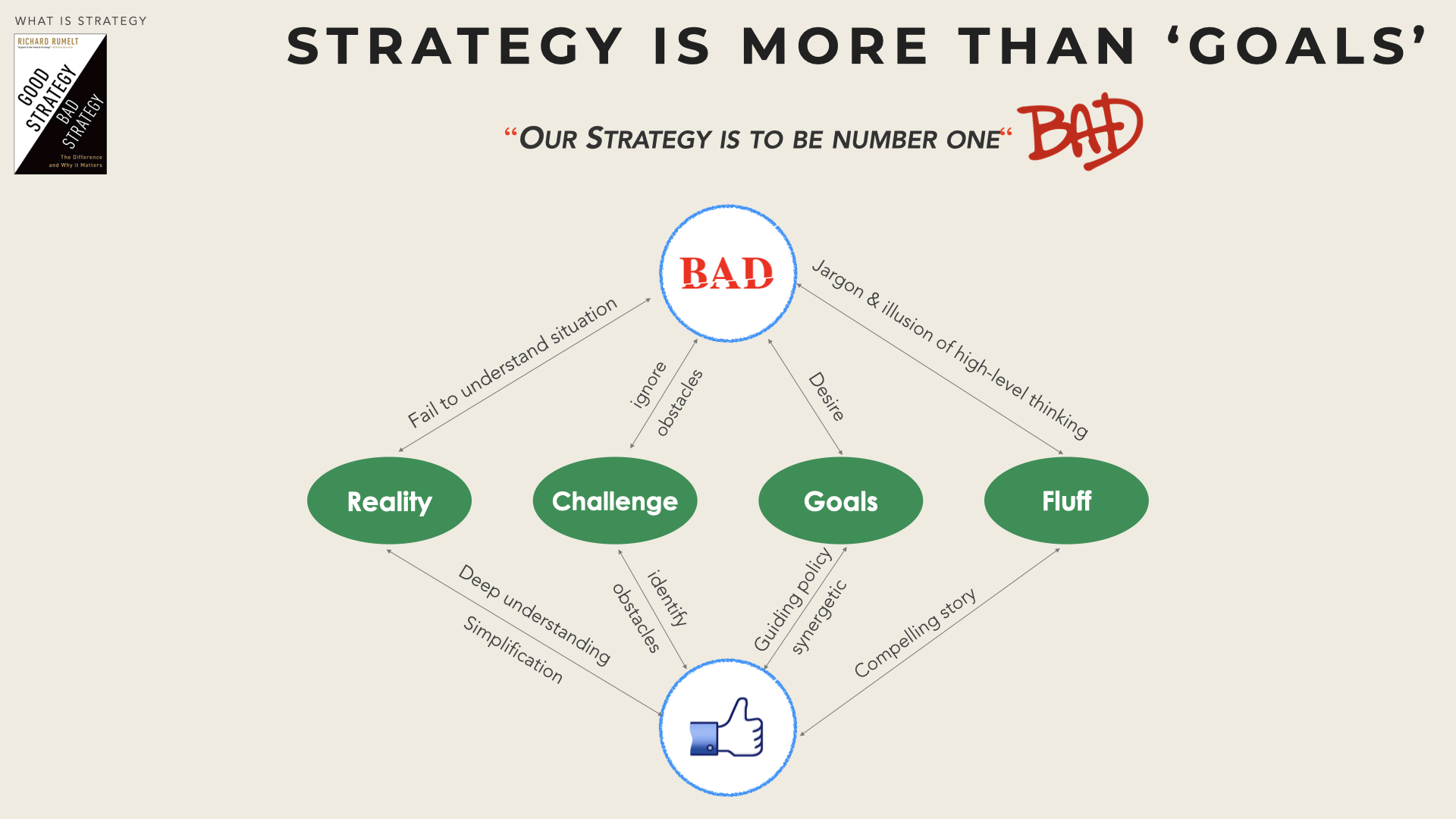

Many so-called strategies are in fact goals. We want to be the number one or number two in all the markets in which we operate is one of those. It does not tell you what you are going to do; all it does is tell you what you hope the outcome will be. But you’ll still need a ‘strategy’ to achieve it.

The assimilation of strategizing with the (more or less fuzzy) implementation of business fads is the central topic of Good Bad / Bad Strategy by R. Rumelt of UCLA Anderson School of Management. ( [Rumelt11] )

“A good strategy does more than urge us forward toward a goal or vision; it honestly acknowledges the challenges we face and provides an approach to overcoming them.” - Rumelt

According to Rumelt, a (good) strategy identifies the one or two critical issues or challenges in a situation — the pivot points that can multiply the effectiveness of effort — depicts a way to deal with them and then focuses and concentrates actions and resources.

As a result, a (good) strategy must clearly:

Understand the situation and simplify the complexity of reality down to actionable factors,

Identify the challenge(s) or roadblock or obstacles that must be overcome, “What’s holding you back from reaching your goals? A good diagnosis simplifies the often overwhelming complexity of reality down to a simpler story by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical. A good diagnosis often uses a metaphor, analogy, or an existing accepted framework to make it simple and understandable, which then suggests a domain of action”.

Define a guiding policy cope with obstacles. While the guiding policy doesn’t describe the details of what exactly should be carried out, it directs and constraints the course of actions (like guardrails along motorways) Furthermore strategy execution should rely on a set of synergetic actions, that is mutually reinforcing.

Articulate a compelling story to explain what obstacles must be dealt with, through what actions and for what expected result. A good strategy must be simple and obvious. It must be designed to be highly coherent and must focus the organisation toward a consistent result.

“A strategy is a way through a difficulty, an approach to overcoming an obstacle, a response to a challenge. If you fail to identify and analyse the obstacles, you don’t have a strategy. Instead, you have a stretch goal or a budget or a list of things you wish would happen.“

By contrast, a bad strategy will usually consists in

a list of unconnected priorities (aka Dog’s dinner Objectives in Rumelt’s terms) that don’t support each other (if not conflict with or undermine each other). A long list of things to do, often mislabeled as strategies or objectives, is not a strategy.

a statement of desire rather than a plan to overcome obstacles. A second type of weak strategic objective is one that is “blue sky”—typically. A simple restatement of the desired state of affairs or of the challenge - or a “blue sky” business vision- is not a Strategy as it skips over the annoying fact that no one has a clue as to how to get there.

the failure to face a challenge characterized by little (if any) understanding of the situation and the absence of obstacle identifications. When a company makes the kind of jump in performance your plan envisions, there is usually a key strength you are building on or a change in the industry that opens up new opportunities. Can you clarify what the point of leverage might be here, in your company?

the use of fluff & jargon as well as inflated words and gibberish to create the illusion of high-level thinking.

Rumelt stresses that in many instances, strategizing (doing the hard work of understanding the situation, identifying key challenges, creating a guiding policy and defining actions to overcome the challenges) is replaced by a template-style strategic planning exercise.

First, a Vision is sketched (what the firm wants to be like in the future) which often starts with “the best” or “the leading.” Then a Mission (the purpose of the firm) is phrased in high-sounding and politically correct terms, completed by Values (non-controversial and usually very trendy). Strategies are then defined as some aspirations/goals.

Usually, no one would argue against the vision, mission, and goal statements, but no one is really inspired by them either.

There is no silver bullet

Each situation calls for its own interpretation and own problem-solving approach that needs to be designed purposely. Consequently, strategists must remain very open and flexible: they must adapt themselves to the organisation for which they work and to its constraints.

Each strategist must discover the few frameworks or models that she/he finds the most meaningful and can use as her/his own navigation aids.