Portfolio selection

Strategy is about making choice, about allocating resource to the best projects or strategic options.

A firm usually faces several options : for instance developing new products or entering a new business (diversification). Not all the options can be pursued at the same time (remember scarcity of resources). The firm needs to prioritise the various options and down-select the few it wants to implement.

Even a single strategy elaboration project can produce more than one proposal. It is not uncommon that several strategic profiles are generated out of the formulation phase. It is then necessary to rank the various profiles and point out a rationale for recommending one option/profile rather than the others. Many criteria and attributes can be taken into account to compare the various strategic options. One obvious criterion is the total amount of resources (financial, human, lead-time) that the firm is ready or capable to engage into the strategic move. Risk level is also a major aspect to consider (some firms are more risk avert than others). These two criteria define a kind of envelope within which several options can be ranked.

Selection is usually a twofold process: first, the options that wouldn’t work or could be achieved are eliminated. Then the remaining options are ranked according to some objective function.

The options that are eliminated can correspond to many different situations. It can for instance, be a scenario that proved not to be technically feasible. It can be a strategic move that would be prevented by too many and/or too high barriers. It may also be a project for which the inherent risk is not compensated by a sufficient return on investment. Last but not least, it may be a proposal that would be too remote from the firm’s culture or wouldn’t meet its corporate social responsibility values.

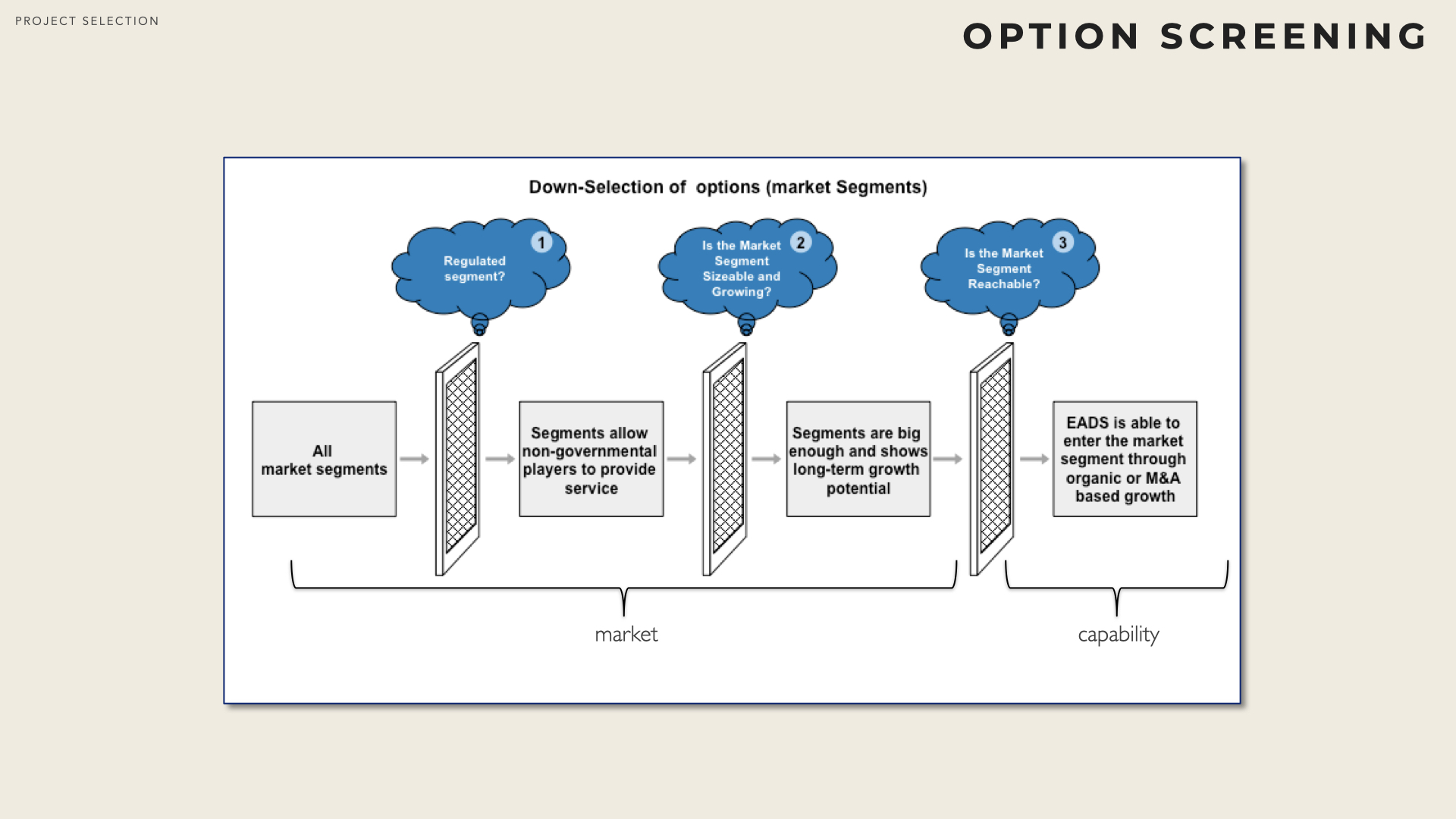

Criteria are used to down select the options that can work and reject the others. Down selection can start very early during the analysis & formulation phase (especially to reject options). It is always a good practice to explicit all the criteria used to rank the various options. Even if evaluating an option against such criteria can be to some extend subjective, it is better to try to make explicit appraisals.

The down-selection usually occurs at the end of the formulation phase (at least to check that the proposals meet the objectives while complying with the constraints). However, option elimination usually starts very early. It is therefore very important to record the reasons for which an idea / option is kept or rejected. Indeed, criteria can evolve during the analysis and it might be necessary to revisit some ranking/selection/rejection.

Matrices

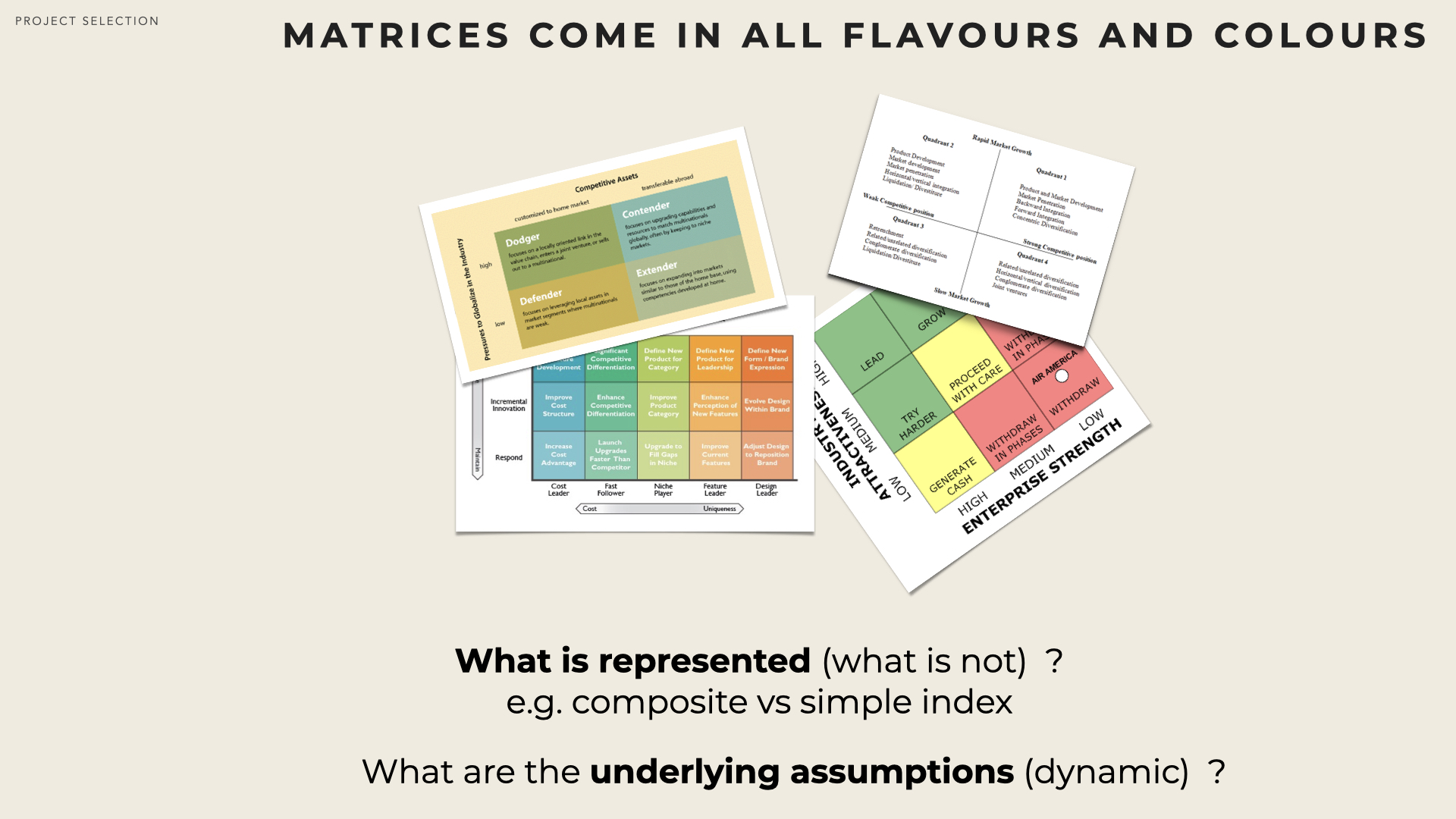

Matrices are very often associated with the practice of strategy. A good strategist would have to produce nice looking charts and arrays from which the purpose a firm and key management actions can be derived and illustrated. Reality has become a bit different though. Nowadays, people have learned to become cautious - even sometimes skeptical - when they see nice looking charts.

It is however important to recognise the most common matrices and understand what they represent (and may be even more important what they don’t represent).

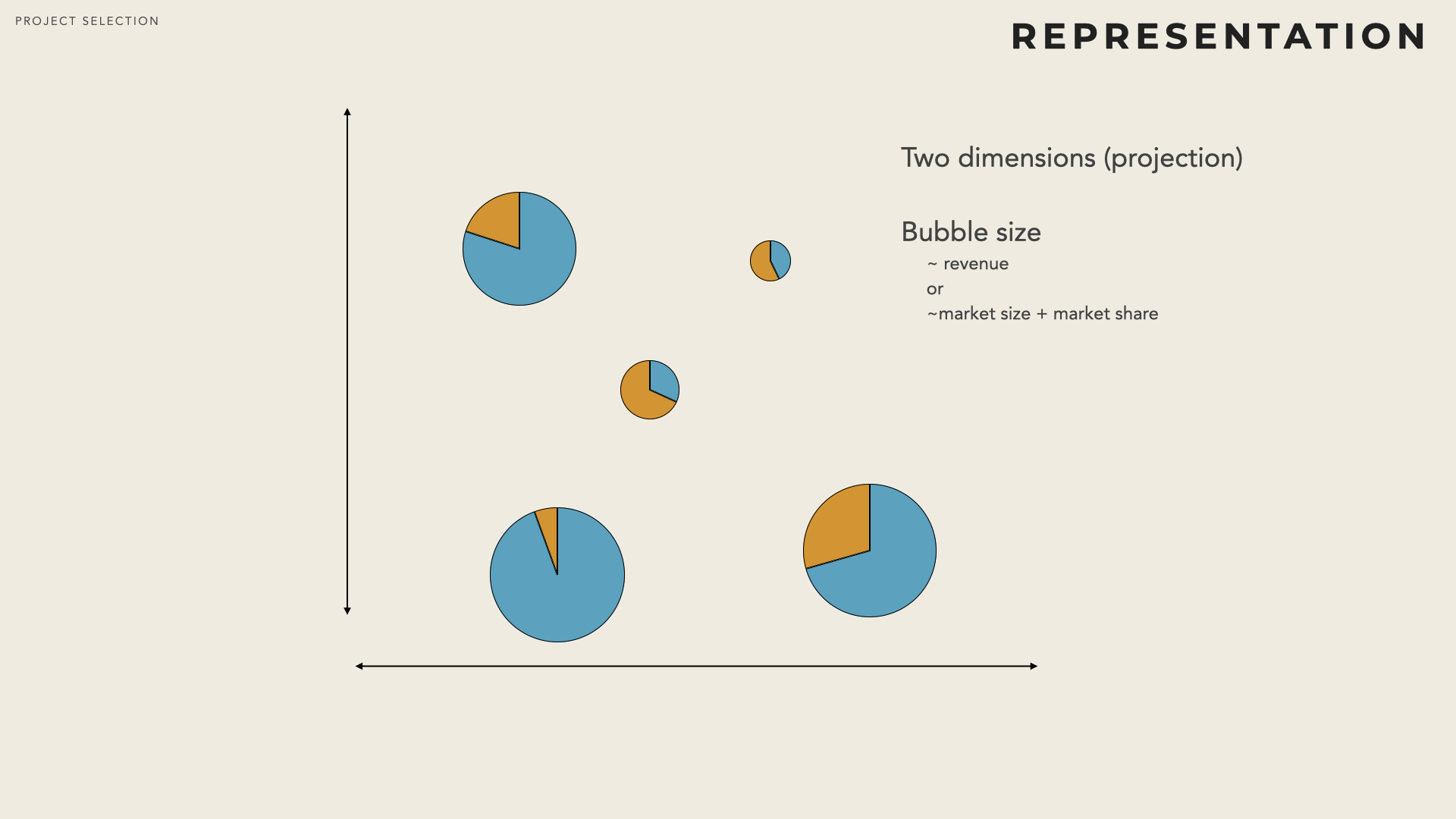

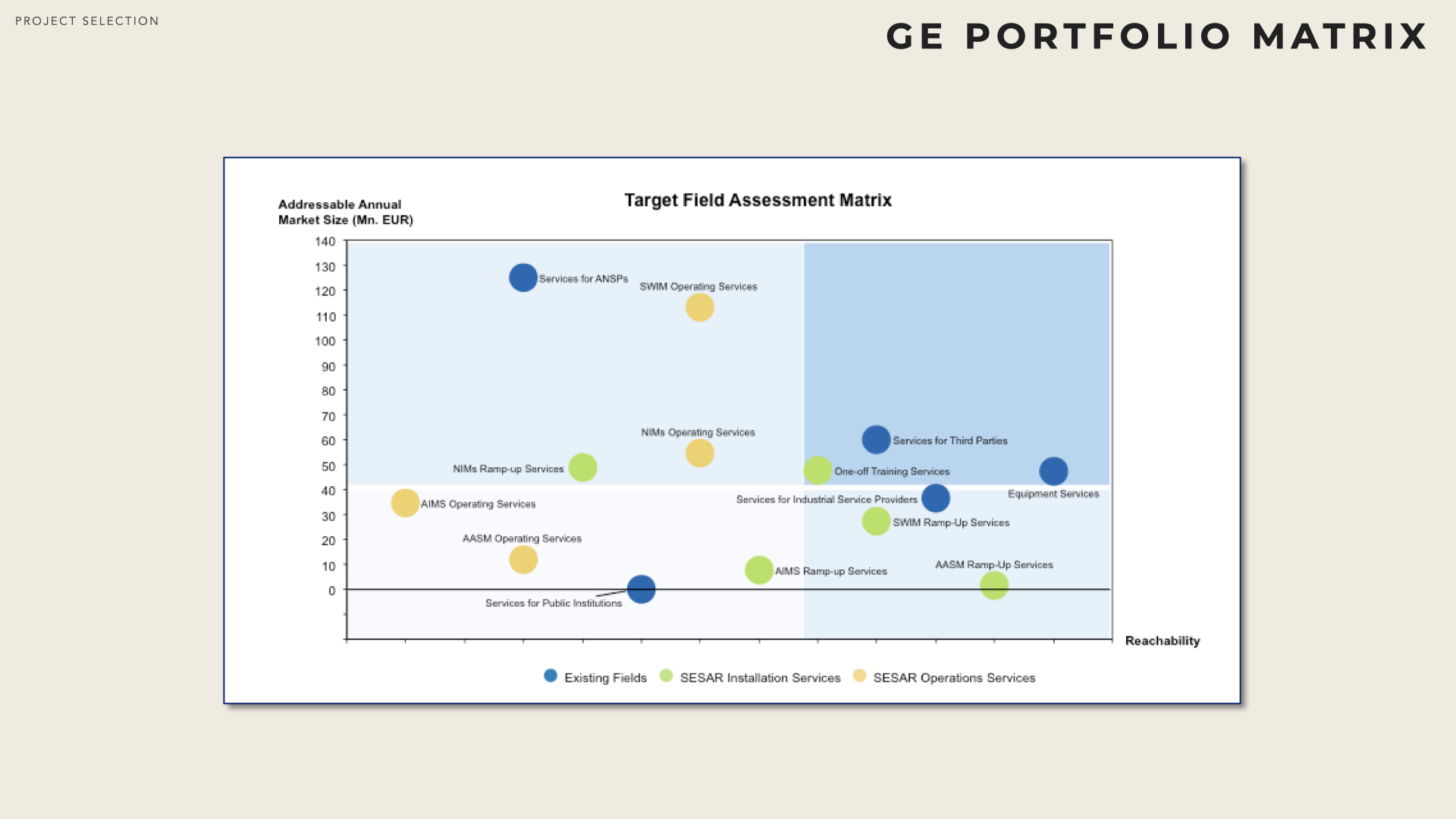

A matrix can be used to visualise the current status of a firm’s portfolio. A two-axes matrix is a mean of representation: it projects more than two dimensions on a plane.

The number of bubbles indicate the corporate scope (how many and which business areas are covered), while the corporate distribution (relative size of the covered businesses) can be seen from the size of the bubbles (or the market share sector).

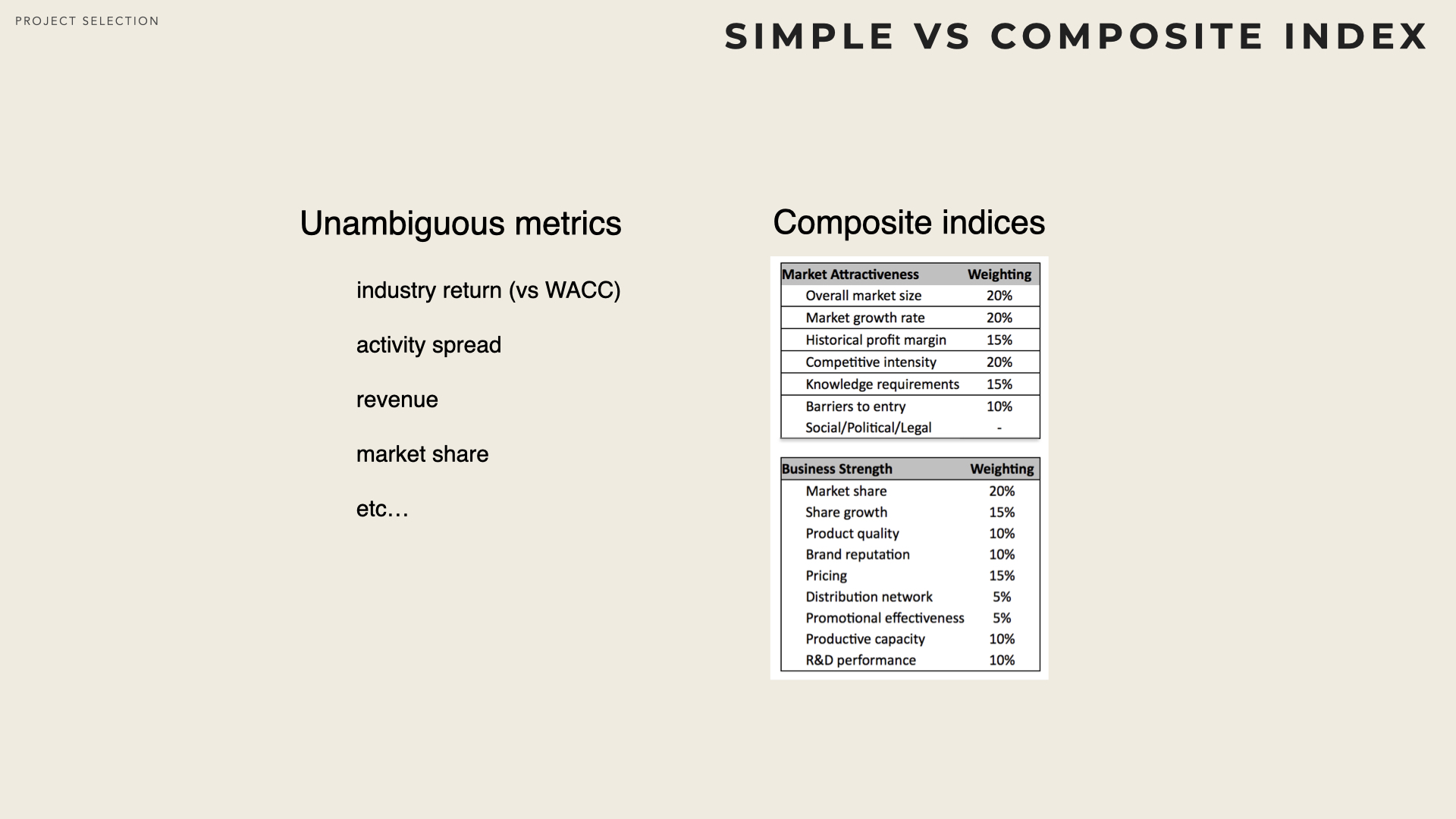

The dimensions against which the various businesses are mapped can correspond to simple attributes (e.g. revenue, spread, etc…) or composite indices.

Composite index are richer (they take into account more elements and are more representative of a complex reality). However, it gets soon very difficult to avoid (very) subjective assessments.

Strategy matrices, however, are also often used as prescription tools : the various quadrants of the matrix call for different management actions. It is then absolutely paramount to understand what are the underlying assumptions that drive such recommendations. Applying a corpus of recommendations to a situation that doesn’t meet the pre-requisite or doesn’t correspond to the situation for which the tool was designed, can lead to very counter productive decisions.

BCG Matrix

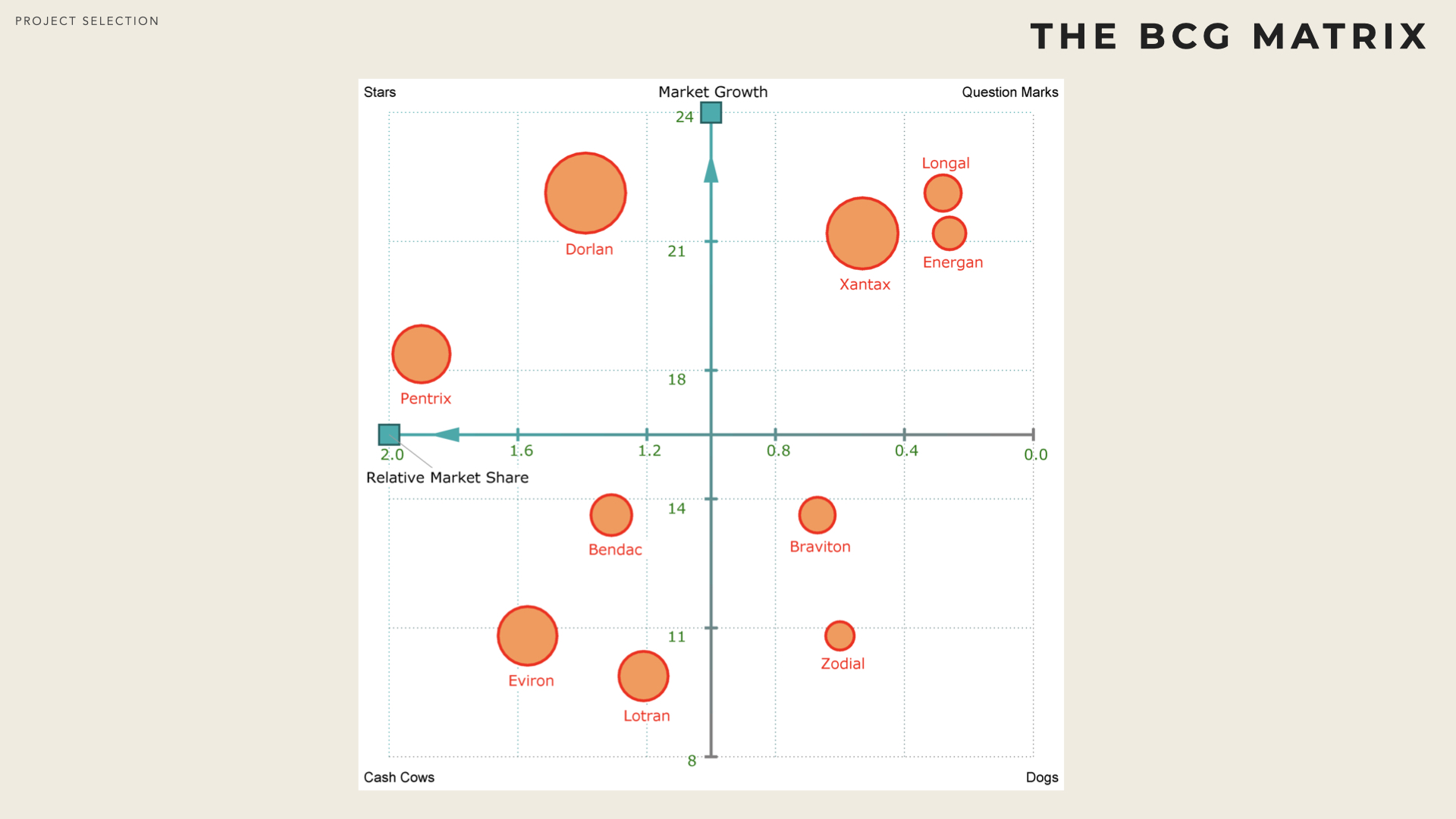

The Growth Share chart (aka BCG Matrix) was created by Bruce Henderson (the founder of the Boston Consulting Group) in the early 70’s.

The chart relies on two axes : the relative market share and the growth rate of the market. It is noteworthy that while the market share can be computed from current data (although it is not always easy to figure out the revenues generated by competitors) the (future) growth of the market is more subjective (should the growth remain stable? increase? decrease? On what rationale?).

The focus with this tool is on cash (profit) and on ensuring the proper identification / balance of cash generating vs. cash consuming activities.

The two major underlying assumptions are that

Unit costs are mainly driven by economies of scale. Hence the competitor that controls the bigger volume can enjoy lower production costs and better return. Achieving high volumes (compared to the industry) is one of the main objectives of a firm.

There exist high growing markets with sustainable demand. As competition is weaker on growing markets - see section on the 5 forces - firms will focus such markets and seek to grow quicker than competition.

That was possibly a good approximation of the economic conditions in the early 70’s, however, this is no longer the case in many countries / many industries.

Typical prescriptions are associated with the four quadrants that each represents a specific category of product / activities:

Cash Cow are products in slow-growing markets for which the firm has high market shares. Such markets are assumed to be mature (they grew and now are stable or even starting to decline). Consequently such mar- kets should be unappealing to new entrants. Competition will remain stable or even decrease. The firm has high market share and should enjoy better economies of scale than competition and better returns. In the 70’s that led to the prescription of reducing investments (product, notoriety, advertising) and cashing in all the profit as long as feasible.

Dog are products in slow-growing markets for which the firm doesn’t have high market share. Again, this is assumed to be a mature, decline market. However as the firm has lower market shares, it is assumed that it suffers higher production costs which degrades its average returns on in- vested capital. Dogs are supposed to be ’end-of-life’ products / activities and the typical prescription is to disengage from these businesses.

Stars are products in fast-growing markets for which the firm has high market shares. The objective here is to maintain the competitive position so that when the market gets mature, the Star will become Cash Cow. The firm needs to keep investing in the product (technology, production pro- cess, branding, customer loyalty) to maintain its dominant position and sustain the growth rate.

Question Marks are products in fast-growing markets for which the firm has not (yet) significant market shares. Most products start as Question marks. However not all the products become Stars and if they fail to achieve high market shares before the market get mature, they may turn into Dogs directly.

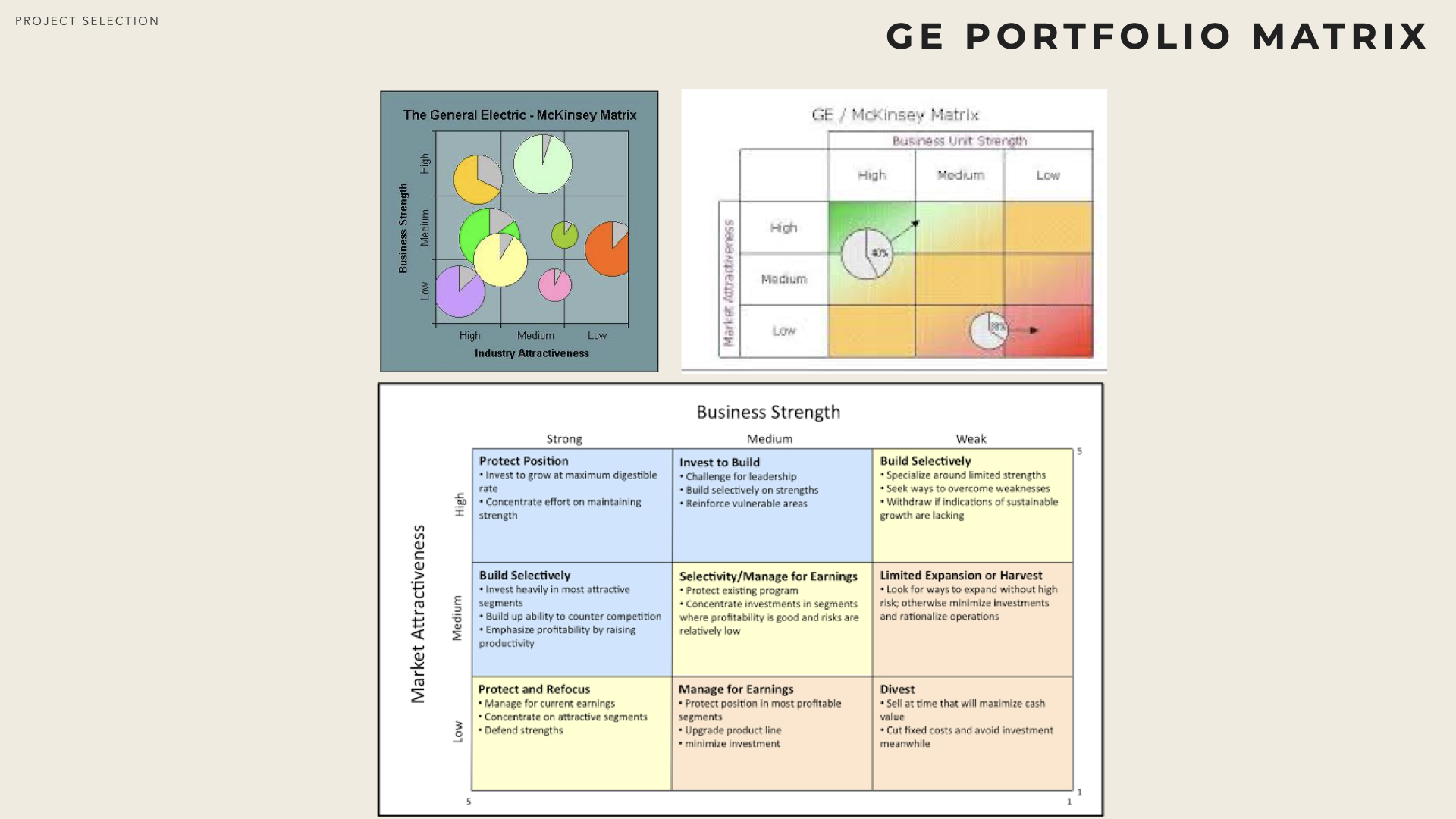

The GE Portfolio Matrix

The GE (aka McKinsey) Portfolio matrix is a slightly more sophisticated version of the BCG Growth-Share matrix. It plots Market Attractiveness against Business Strength and usually uses a 3 by 3 grid (low, average, high) rather than a 2 by 2 grid.

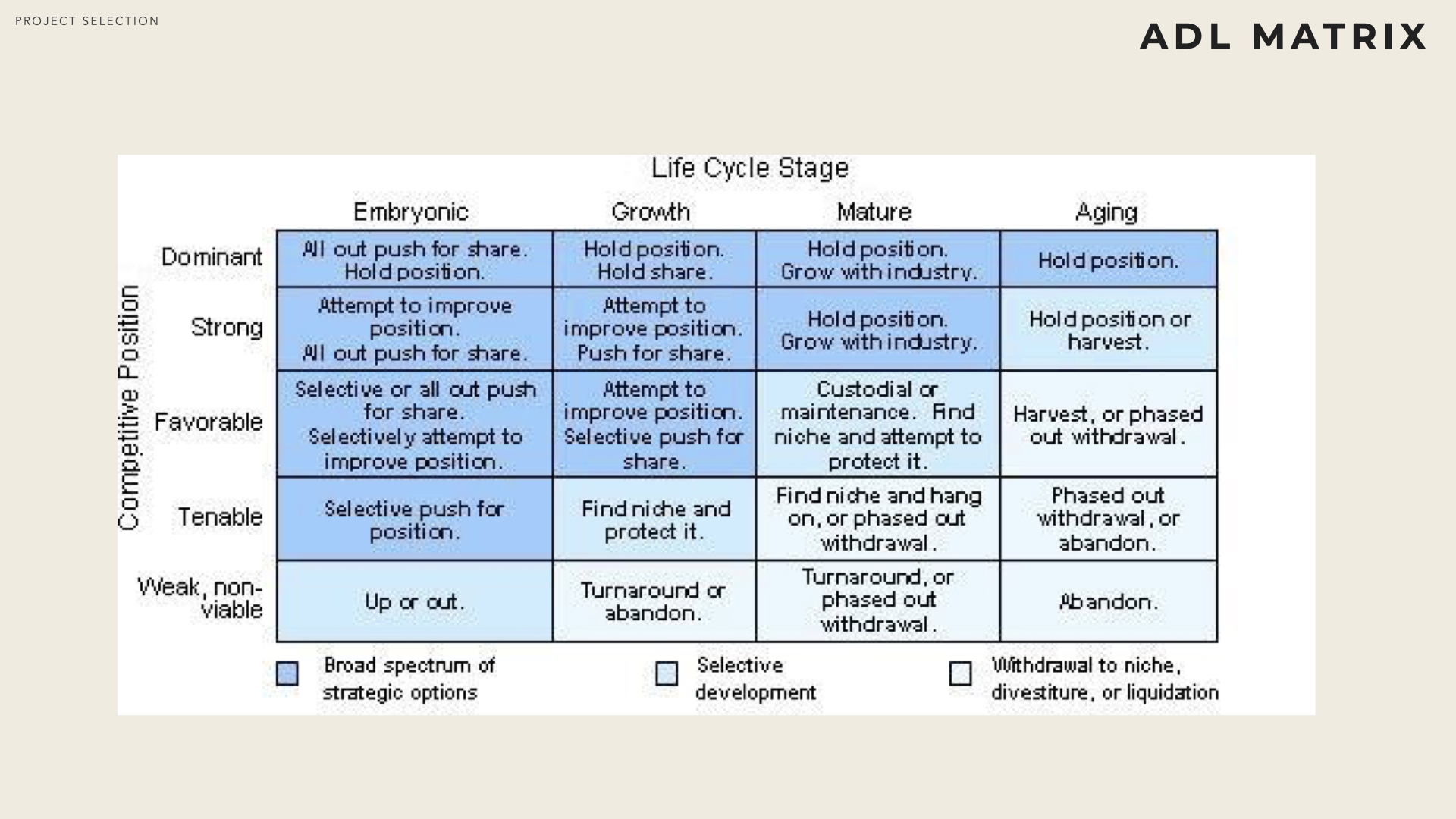

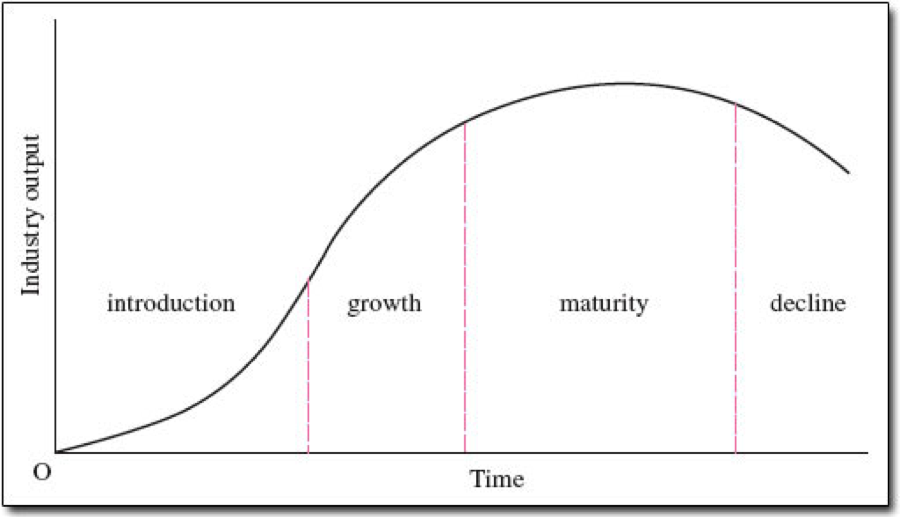

The ADL matrix

The ADL matrix is also known as the product life cycle portfolio matrix. It is similar to the BCG and GE matrix but put the emphasis on the life cycle of the industry / product.