Corporate composition

Introduction

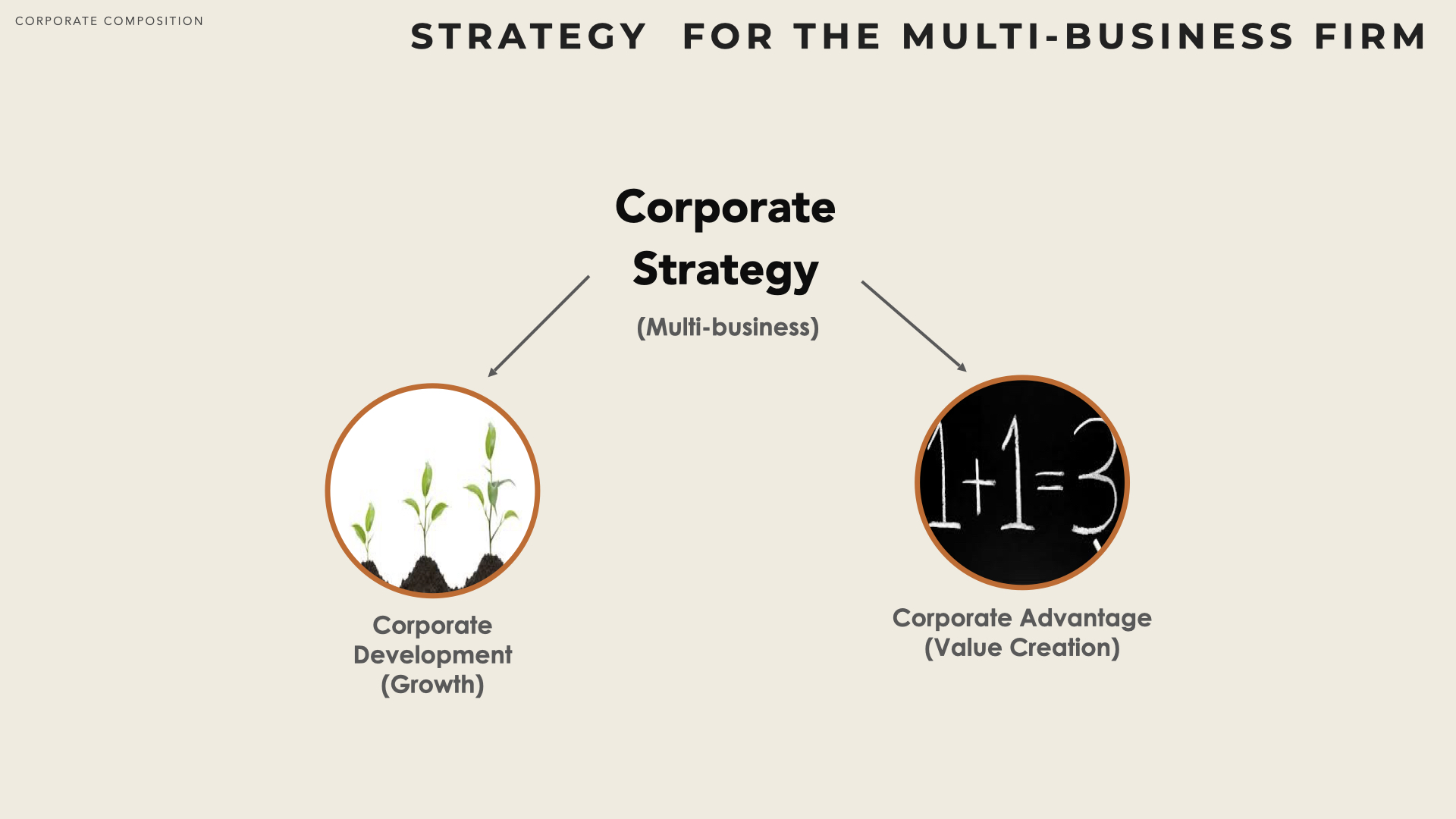

Corporate Strategy aims at finding out if a company should, and if so, how it should compete across several industries.

Corporate Strategy is about selecting an optimal set of businesses and determining how they should be integrated into the corporate whole - De Wit & Meyer

Corporate Strategy being about multi-businesses, it becomes key to define what a ‘business’ is. The usual accepted definition is that a a business is characterised by its business model. So if a firm addresses different segments of customers with radically different value propositions or value architecture, then it is a multiple-business firm.

Now reality, as ever, can be rather blurry. A multinational firm can be seen as comprising different businesses (e.g. multi-domestic firms) or on the contrary as offering worldwide a single value proposition (e.g. trading firm).

Likewise, when the launch of a new product requires tremendous investment (e.g. a new aircraft programme), it can be viewed as a business in its own right, although the business model remains unchanged.

The central question of Corporate Strategy: is adding a new business creating value? Is the company with its new business worth more than they were worth separately? If not adding the new business will destroy value and the company is better off without that business.

This therefore revolves into two main aspects:how to further develop the company ? and how to ensure some form of corporate advantage?

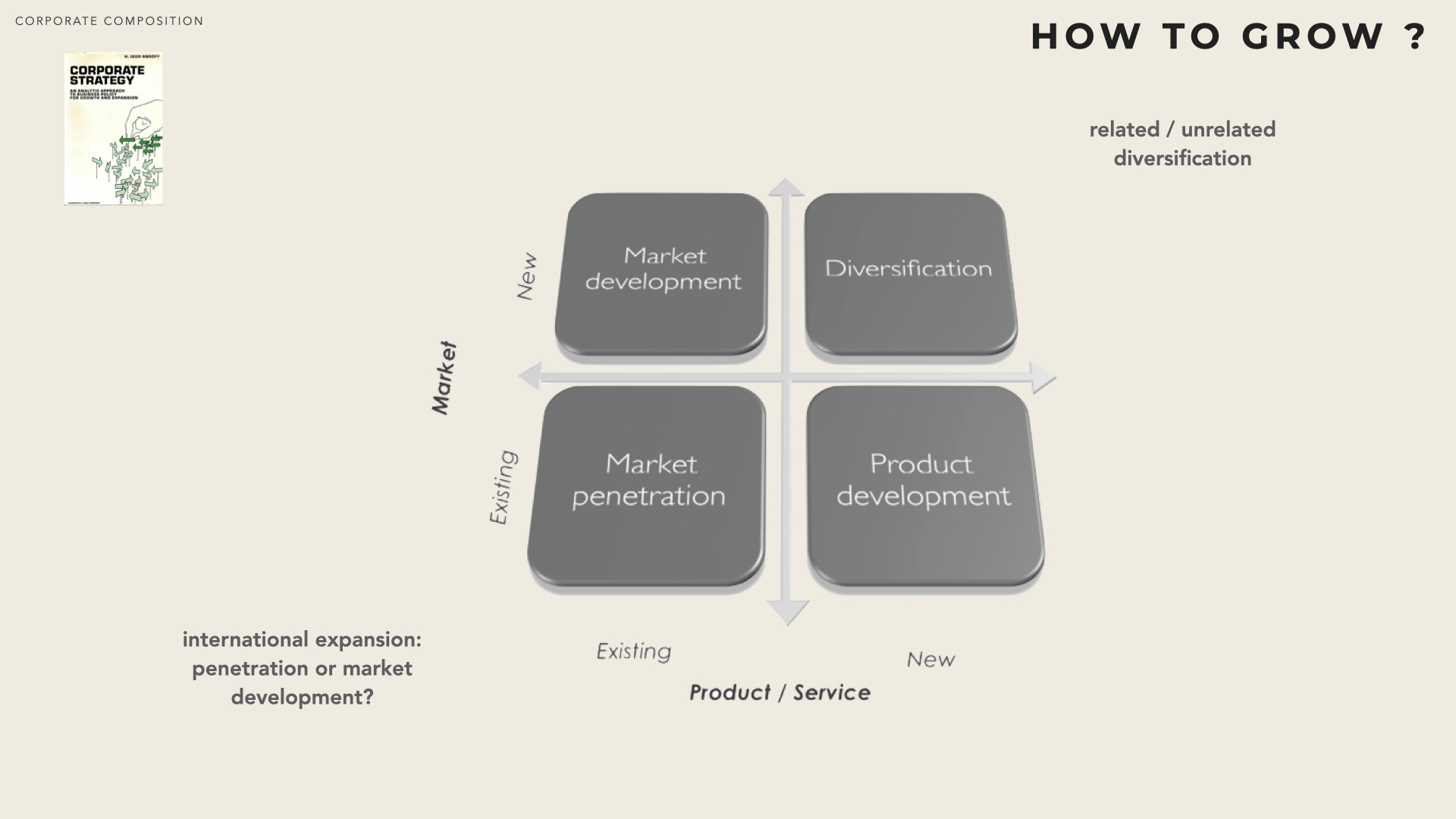

Before looking at how Value can be created, let’s seek to understand the overall mechanics by revisiting the famous Ansoff’s framework.

The Ansoff’s Framework

Ansoff introduced his matrix in an article published in 1957 in the Harvard Business Review. It portrays the four alternative growth strategies, by considering existing products vs. new products, and existing markets vs. new markets.

Market Penetration

Market penetration consists in increasing the business through offering the same product/service to the same market.

With Market Penetration, the firm seeks to achieve growth with existing products in their current market segments, aiming to increase its market share. Usually more business volume translates into some cost efficiency (with associated potential profit gains).

In a growing market (e.g. developing market) simply maintaining the market share will result in growth. In addition, opportunities to increase market share may exist, if competitors reach capacity limits.

Market penetration is the least risky strategy since it leverages many of the firm’s existing resources and it requires no change in strategic capabilities. However, market penetration has limits and once the market approaches saturation another strategy must be pursued if the firm is to continue to grow.

There are two major downsides to Market Penetration:

Retaliation from competitors rivalry among competitors is likely to get exacerbated, especially in mature markets. Market penetration in low-growth markets often triggers horizontal integration and consolidation (one of the player seeks to acquire its competitors).

Legal constraints Anti trust regulations aims at limiting market power. Therefore authorities are likely to prevent consolidation beyond a certain limit.

Note: Retrenchment (a firm deciding to withdraw from a less attractive market) is the opposite to market penetration.

Product Development - Market Development

Market development and Product development are sometimes called related diversification (or adjacent diversification). The idea here is to either offer new products to existing customers or to propose existing products to new markets. Product development is usually the most challenging option.

With Product Development the firm develops new products and/or services – i.e. with different technologies – targeted to its existing market segments. A product development strategy may be appropriate if the firm’s strengths are related to its specific customers rather than to the specific product itself. When there is customer bonding (strong customer relationship, available customer data, …) the company can leverage its strengths by developing a new product /service targeted to its existing customers.

Depending on the degree of relatedness, Product Development may imply acquiring/developing new strategic capabilities (e.g. new processes, new technologies, new know how, etc). Therefore it usually carries more risk (e.g. delays, cost overruns, failure) than simply attempting to increase market share.

With Market Development the firm seeks growth by targeting its existing products to new market segments. Market development options include the pursuit of additional market segments (e.g. addressing additional user needs) or geographical regions (including internationalisation).

The development of new markets for the product may be a good strategy if the firm’s core competencies are related more to the specific product than to its experience with a specific market segment. Because the firm is expanding into a new market, a market development strategy typically has more risk than a market penetration strategy.

Diversification

With Diversification the firm grows by diversifying into new businesses by developing new products for new markets.

Diversification is the most risky of the four growth strategies since it requires both product and market development and may be outside the core competencies of the firm. However, diversification may be a reasonable choice if the high risk is compensated by the chance of a high rate of return.

Other advantages of diversification include the potential to gain a foothold in an attractive industry and the reduction of overall business portfolio risk.

Diversification can occur at business level (expanding to new segments of the industry) or at corporate level (entering new businesses out of the scope of current activities). Differentiating diversification from market development or product development can be however rather subjective, as it depends on the way “new product” and “new market” are interpreted.

It is usually considered that there is diversification when and if a firms tries to develop a new strategic segment, which usually requires new capabilities. Although diversification can be accessible through pure organic growth (developing existing resources & competence), it is often associated with external growth.

Complement: Other terminology

Some Academics use the term ’diversification‘ for any type of growth. An adjective is used to characterize the move, according to the degree of similarities between the industries where a firm is already operating and the industry in which it tries to step in.

Concentric diversification consists in a strategic move where there are technological similarities with the existing operations of the firm. In such a case, the firm can leverage its resources and competences and organic growth can be the right option.

Horizontal diversification a firm decides to enter a business that requires new technologies or technical know-how (likely to drive external growth), but which may appeal to their current customers.

Vertical diversification (or integration) a firm integrates a part of its supply chain or its distribution channels.

Conglomerate diversification corresponds to situation where the firm tries to enter a business that has neither technological nor commercial synergies with its existing activities. The rationale for such diversification (also named unrelated move) is usually purely financial (risk diversification, access to credit, etc) except if it prepares other strategic moves (e.g. entering a new geographical market). However such moves are usually not welcomed / trusted by investors and the share price usually suffers a conglomerate discount that can exceed 25% (the total company value is less than the sum of its parts).

In practice, diversification can be tackled from two angles. On the one hand, a firm can consider new potential activity domains and assess in which of these domains it can gain or strengthen a competitive advantage (or at least appraise what are the reconditions required to do so). On the other hand, a firm can start from an appraisal of its specific resources & competences and look for domains where its capabilities would be a source of differentiation. More often than not, the two approaches are combined.

A firm can also view diversification as a means to reduce or counter-react to threats. This would typically be triggered when the negotiation power of its customers and/or suppliers is changing.

Diversification drivers

Several objectives can explain why firms are considering diversifications:

Economies of Scale, Scope diversification can yield efficiency gains through applying the organisation’s existing capabilities to new markets or products.

Leveraging corporate management competence corporate level(usually HQ) may bring capabilities to the various owned businesses (e.g. branding, marketing, procurement, security), even if they share little resources at operating-unit level.

Exploiting superior process share best practice and access to resources, especially when markets (e.g. labor market, capital market) are not efficient. In that case a conglomerate can bring more value than would the sum of its parts.

Increasing Market Power a large portfolio / turnover reduce the risk of extreme competition as the retaliation power increases.

Generate synergies gain benefits where activities or assets complement each other so that their combine performance is greater than the sum of the parts.

There are also some bad reasons to undergo diversification. This usually translates into value destruction for the company:

Responding to market decline re-investing in a diversified business because the core business doesn’t require / justify any further investment. In that case, orthodox finance theory suggests that extra-fund should be given back to shareholders.

Spreading risks shareholders can manage their own risk mitigation portfolio. This is different when a business has a majority shareholder who may wish to protect its investment.

Managerial Ambitions CEOs sometimes would rather make the headline in newspaper than create long term value for the company they are leading.

Corporate Value

Corporate strategy should be guided by the vision of how a firm, as a whole, creates value. In any multi-business company, an efficient corporate strategy can contribute to value creation. Conversely a less efficient corporate strategy can destroy value.

”How can you tell if your company is really more than the sum of its parts ?” Are the benefits of corporate membership greater than its costs ?

How is value created

Corporate strategy should be guided by the vision of how a firm, as a whole, creates value. In any multi-business company, an efficient corporate strategy can contribute to value creation. Conversely a less efficient corporate strategy can destroy value.

For Corporate Strategy, a firm competes with other potential owners for businesses.

Is the firm the best owner for a given business (i.e. would the business worth more to someone else),

How can you obtain “corporate advantage” i.e.yield more value by combining several businesses

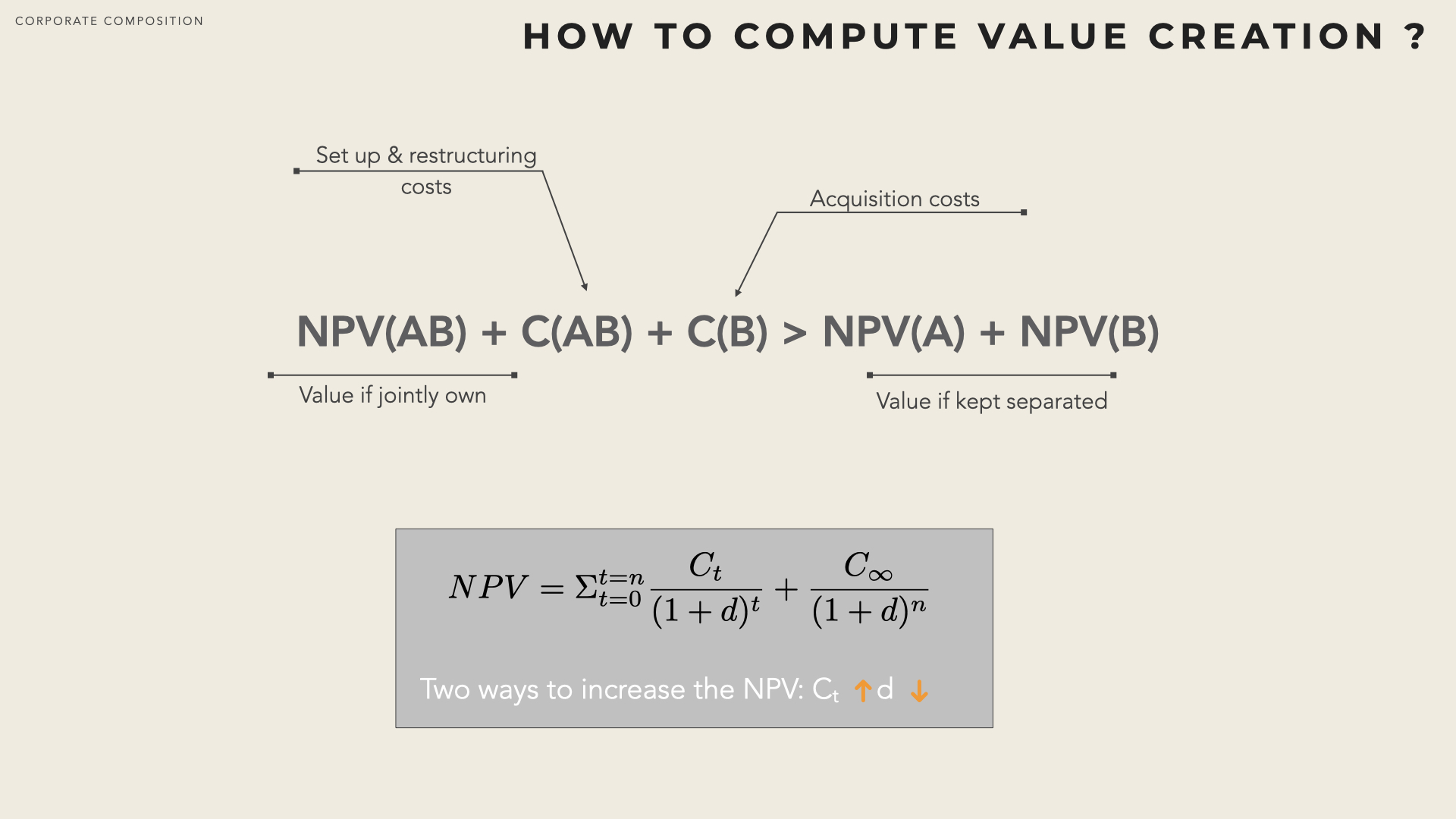

A firm has Corporate advantage if owning together two businesses A and B, yields more value than the sum of the value of the businesses owned separately - that is V[AB] > V(A) + V(B).

Net create value

If the value creation inequality above don’t hold, then the firm should not pursue any attempt to own the business B, as it would destroy value. If it holds the firm still needs to check that the costs of acquiring the firm B (if firms A will own it) and the cost of establishing the joint control (if applicable) are off-set by the extra value.

The owner of a firm has cash flow rights over returns, that must be discounted to take into account the time value of money. Therefore there are fundamentally two ways to increase the NPV :

increase cash flows for instance by increasing revenues (cross-selling opportunities) or decreasing costs (synergies)

decrease the discount rate mainly by reducing systematic risk.

Types of control

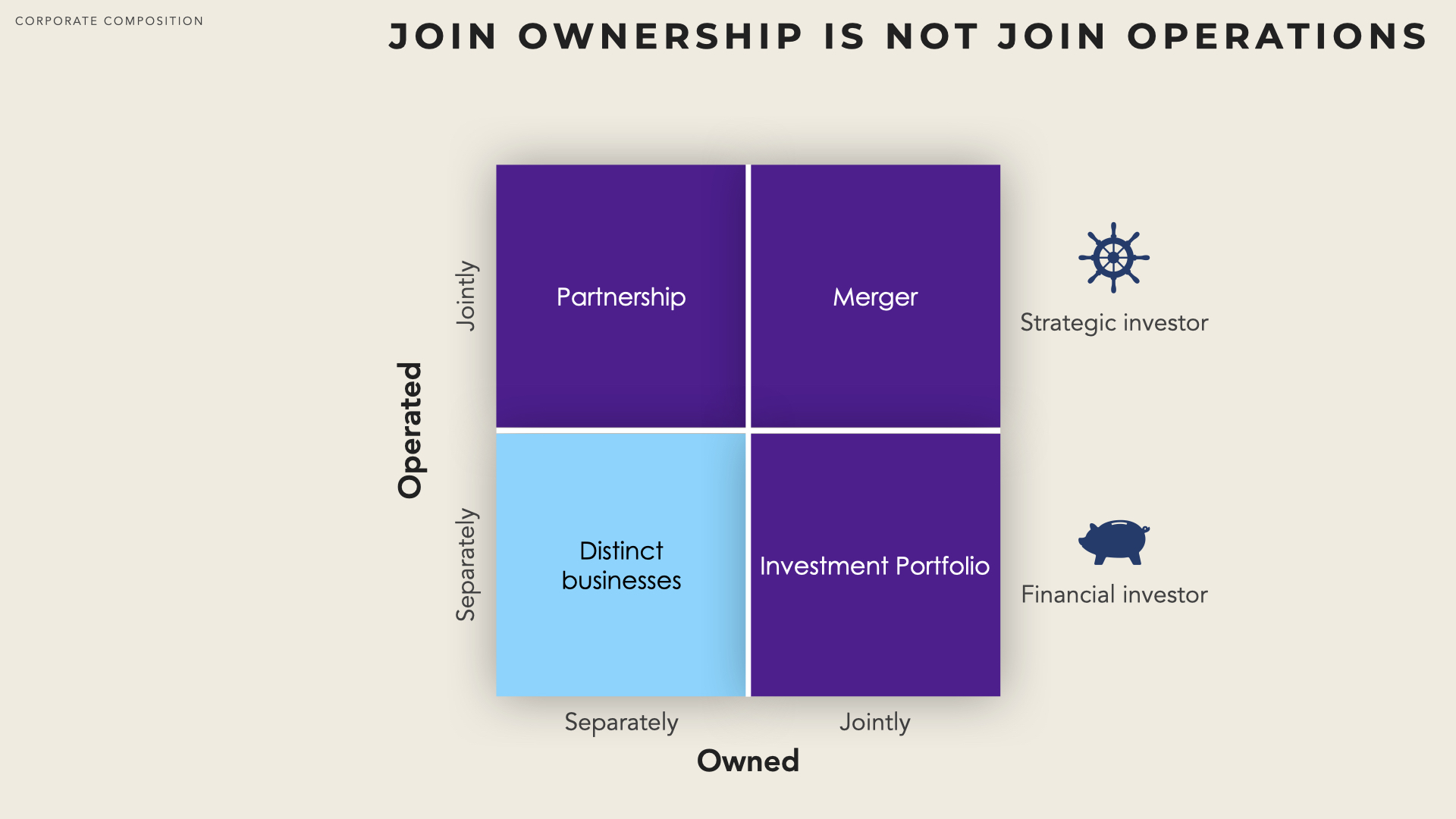

The two types of cost refer to two mechanisms which can be brought into play in the control of a business by a company: a business can be owned jointly and/or operated jointly.

There are four combination of ownership / operations control:

Distinct businesses if business A and business B are neither owned jointly nor operated jointly, they are two separate and distinct businesses.

Investment portfolio if their are owned jointly, but not operated jointly it means that the same company has stakes (possibly minority stakes or majority stakes) into the two businesses, however the two businesses remain totally operationally independent. Decision-making is not coordinated across the two (they can even compete against each other). Financial investors (investment fund, private equity) are more likely to use this form of growth.

M&A at the opposite, if a company can own a business and operate it jointly with its other businesses. The integration can be total (merger) or partial. Strategic investors are likely to use this form of growth.

Partnership It is also possible to operate two businesses jointly, while not have joint ownership rights. This includes formal and non-formal alliances as well as joint ventures (that can as well be seen as M&A).

From theory to reality

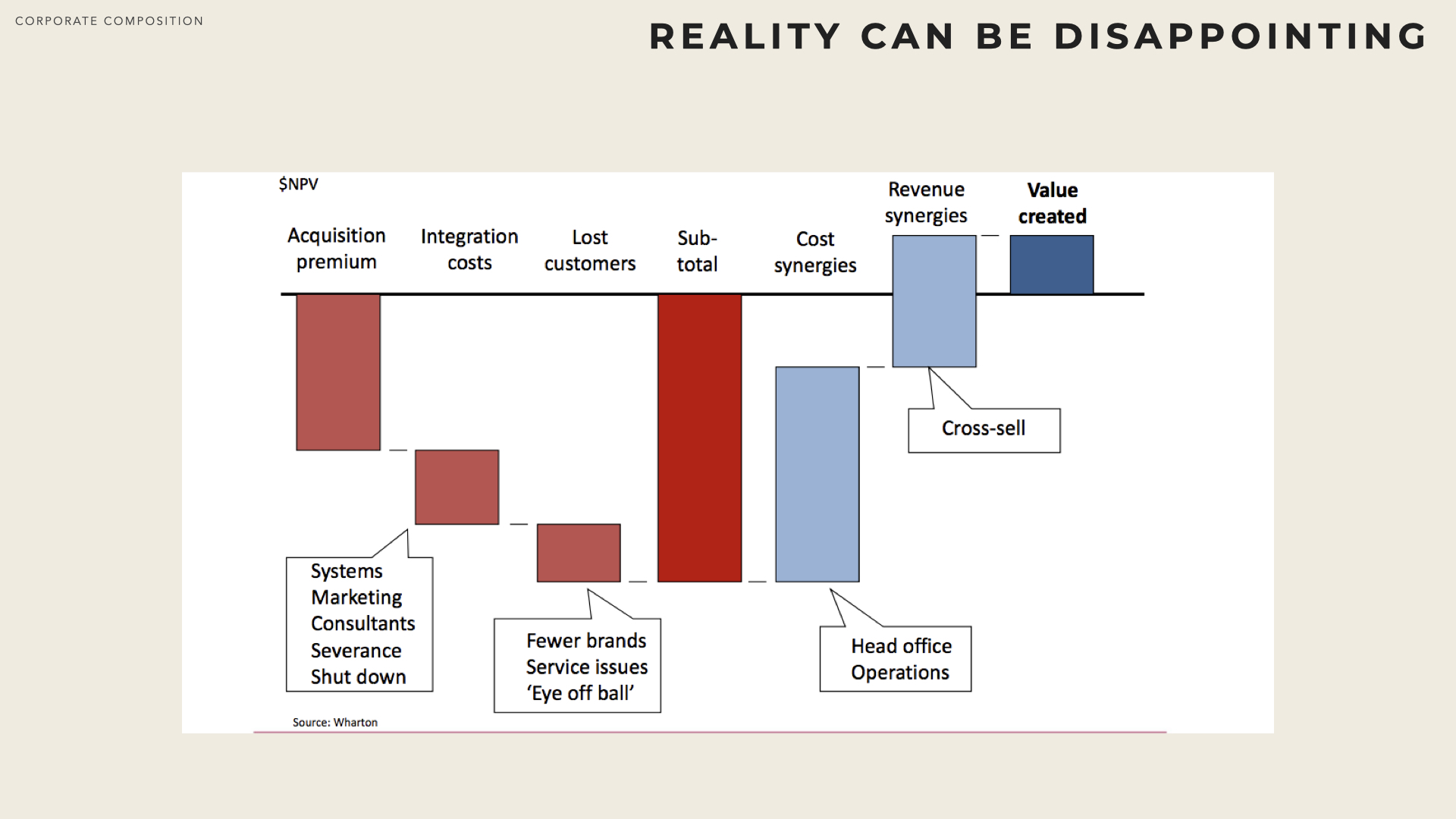

In real life, when a company is acquired, the acquisition price the always higher than the listed price. The difference is called acquisition premium.

Strategic Management is concerned with relating firm to its environment, to successfully meet long-term objectives. ( [DeWit10] )

In addition to paying the former shareholders, the new owner needs to pay execution costs (to bankers, consultants, etc…) and post merger integration costs (e.g. alignment of the management information systems, finance reporting, etc…).

It is also very common that during first months after an acquisition the customer base shrinks: some existing customers decide to switch to other suppliers.

To compensate for all these cost items, the new owner must create cost synergies (doing the same with less costs) and revenue synergies (e.g. cross-selling and leveraging a larger sale force). Value is created only if the sum of the synergies exceeds the sum of the costs.

Frameworks

Corporate Advantage framework

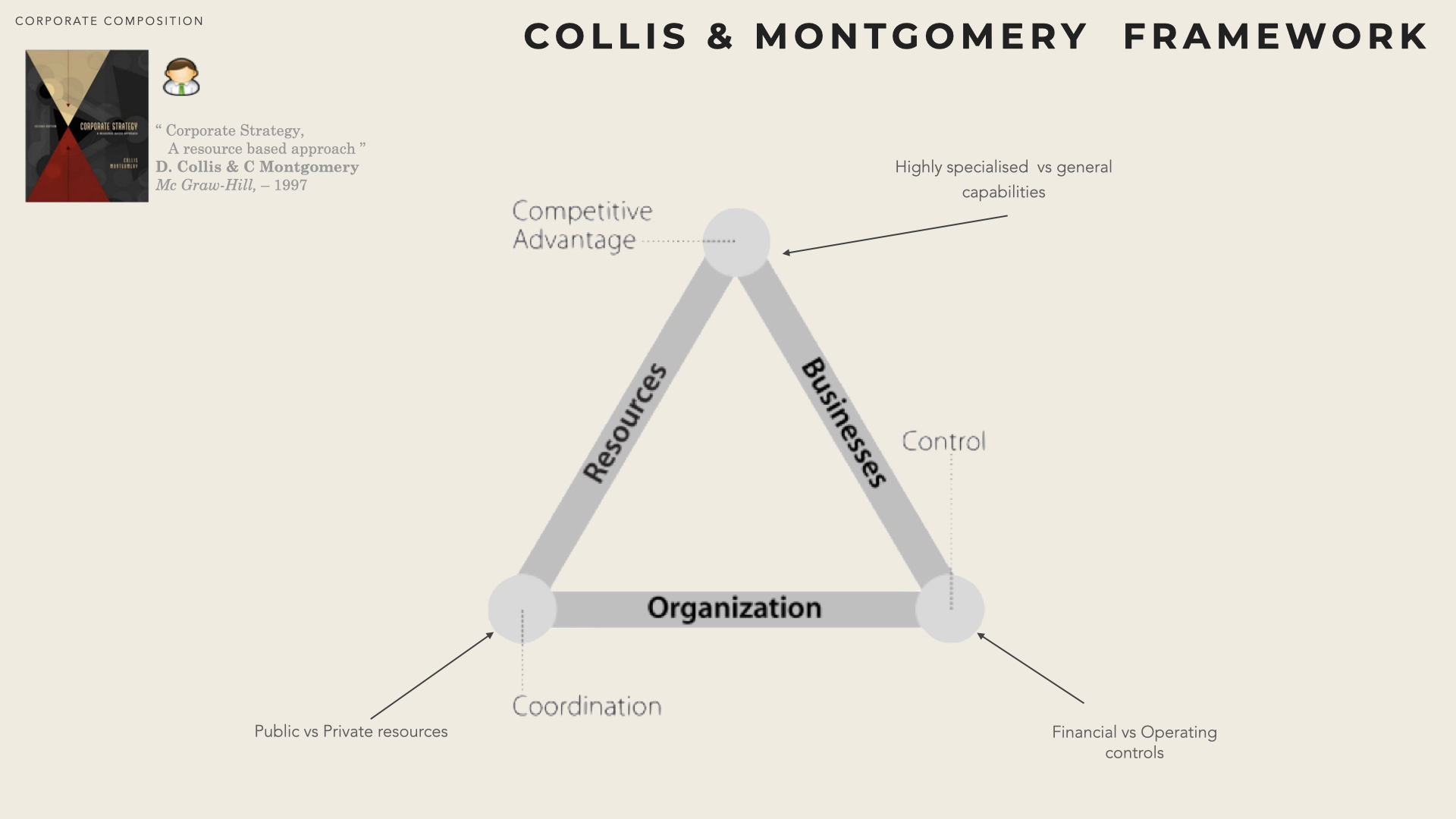

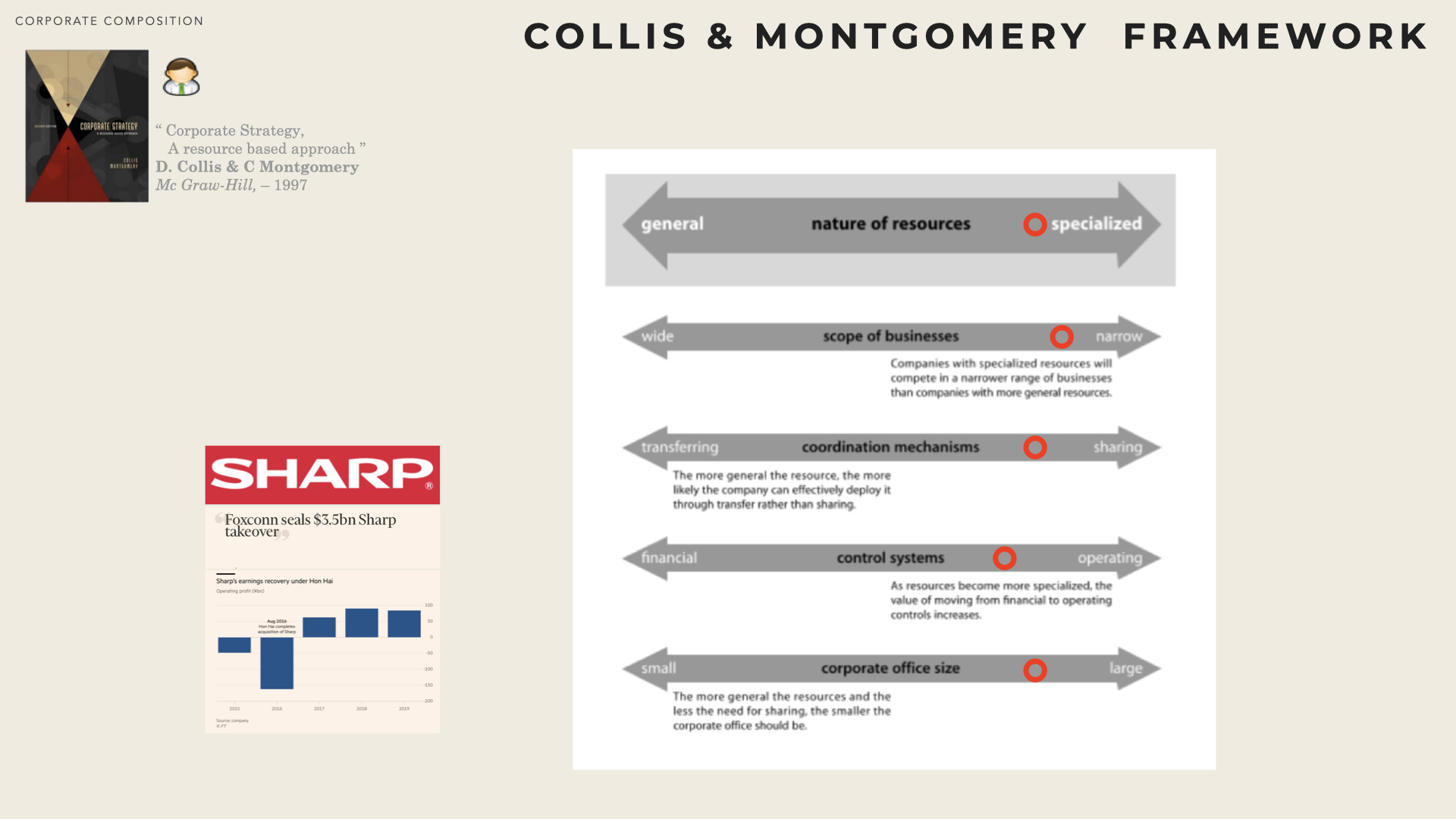

This section borrows from an article published by Collis & Montgomery in Harvard Business Review ( [Collis98a] ) . According to them, creating viable corporate strategies requires combining three major ingredients: resource, business and organisation.

Corporate Strategy requires working on core competence, restructuring the corporate portfolios and building organisations. Furthermore the true essence of any corporate advantage is turning these elements into an integrated whole. - Collis & Montgomery

A successful corporate strategy must therefore be a constructed system of three interdependent parts:

When a company owns the resources that are critical to the success of its businesses, it possesses a competitive advantage.

When the global organisation is configured to leverage those resources into the businesses, synergy can be captured and coordination achieved.

Finally, a good fit between a company’s measurement & reward systems and its business logics allows strategic control.

A. Resources

The firm’s resources define the businesses that make sense for it to own and those that don’t. The resources that provide the basis for corporate advantage range along a continuum, from the highly specialised to the very general:

Firms with highly specialised resources (e.g. technology specific) will usually compete in a narrower range of businesses (where the resources are relevant and can deliver a competitive advantage)

Firms relying upon more general resources (e.g. management skills, corporate governance) can own a large variety of businesses.

The type of resources also defines the most appropriate mode of coordination, from sharing (e.g. common sale force) to transferring (which preserves the autonomy and accountability of the business units).

Managers often fail to recognise that it is about resources and not about product. In their article, Collins & Montgomery give the example of industrial thermostats that require resources such as strong R&D capabilities, expertise in strict tolerance, made-to-order production capabilities, a technically sophisticated sale force. By contrast, in household thermostats the resource expected to be competitive are: product design & appearance, packaging, mass production, distribution through mass marketers & retailers. As a consequence, a firm that is successful in industrial thermostats is unlikely to also succeed o household thermostats. Indeed, although it could leverage some of its knowhow and competences, it would not use many of the factors from industrial thermostats and would lake most of the factors to compete in household thermostats. This is know as the relatedness trap.

B. Coordination mechanism

Corporate strategy seeks to deploy the resources that are key to each individual business. Resources can be either shared among several businesses or transferred across businesses with a minimum of coordination (at arm’s length).

Public resources (e.g. brand name, best practice) are easy to share, as they are non-rivalrous (the use by one business doesn’t reduce the availability for the others). However it may be necessary to ensure that the company continue to invest in these resources and also to prevent from the resource to loose value and/or get spoiled by one business.

Private resources correspond to resources that can be mutualised across several business units (e.g. sale force, MIS, joint procurement, factory). They can be transferred to a specific business or kept at corporate level and shared across several businesses. It usually requires a lot of coordination to reach consensus on the specifications of a shared resource and to reach a compromise agreement.

C. Control System

The corporate centre highly relies on its control system to steer the divisions toward the chosen strategic direction and influence performance in the individual businesses. Choices about what to measure and what to reward are therefore absolutely key.

By and large, control systems are of two types: operating or financial. Financial control holds managers accountable for a limited number of objectives that are measurable (sale growth, return on assets). By contrast operating control aims at appraising managers’ decisions and actions (including when facing unexpected events).

While most companies tend to use a mix of the two, successful corporate strategies clearly emphasise one or the other, subject to the nature of the business in the portfolio and the relative expertise of corporate executives. Financial control is more appropriate in mature and stable industries while in fast moving industries with high levels of uncertainty, operating control is more appropriate.

Example: Sharp

Collis and Montgomery illustrated their triangle model through several examples in a seminal article published in HBR ([Collis and Montgomery, 1998b]). Two examples, Sharp and Nowell, are summarised hereafter.

In 1998, Japanese electronics giant Sharp was generating $14 billion in consumer-electronics (and $24 billion in 2014). Sharp was acquired in 2016 by Taiwanese multinational Foxconn after a USD $4.3bn takeover bid. The description below is based on Sharp’s situation in 1998.

In terms of resources, Sharp seats near the specialised end of the resource continuum. Sharp predominantly relied on a set of specialised technologies (e.g. optoelectronics – they invented the LCD display). Sharp could then expand in many businesses providing that it benefited from the competitive advantage from one of its core technologies (narrow range of business / focused industry). Today Sharp is the major players in LCD panels and solar panels. It offers a large portfolio of products ranging from mobile phones, audio-visual equipment, camcorders, tv sets, home cinema systems, printing devices, microwave ovens, air conditioners, cash registers, fax machines, calculators and flash memory.

We invest in the technologies that will be the nucleus of the company in the future – they should have an explosive power to multiply themselves across many products - Sharp’s CEO, 1997.

Sharp’s technological investments are expensive; they require substantial lead-time and the advantage they bring can get short-lived due to imitation or quick obsolescence. Therefore, it is paramount for Sharp to down select the right investments in its various businesses and to quickly and broadly leverage new technologies throughout the company. As a result, Sharp relies on a large corporate office (in Osaka) as its strategy depends on extensive coordination and shared technological activities.

Coordination is driven by the requirement to efficiently share activities. Therefore the company is divided into functional units rather than product division. R&D and manufacturing for key components (e.g. LCD Dis- play) occur in a single unit where the economies of scale can be exploited. Product managers have the responsibility (but not the accountability) for coordinating the entire set of value chain activities. In addition, many cross-unit committees ensure the optimal allocation of shared resources. This mechanism of coordination is time-intensive and costly. However it is required to leverage the technological investments.

Control System: due to its functional structure, Sharp requires a very different control system than a simple divisional P&L. Promotion (on the basis of seniority and skills exhibited over time) rather than annual compensation is the most powerful incentive. As pooling investment is key (and not a natural trend in any firm), managing conflicts and tradeoff between units is pivotal.

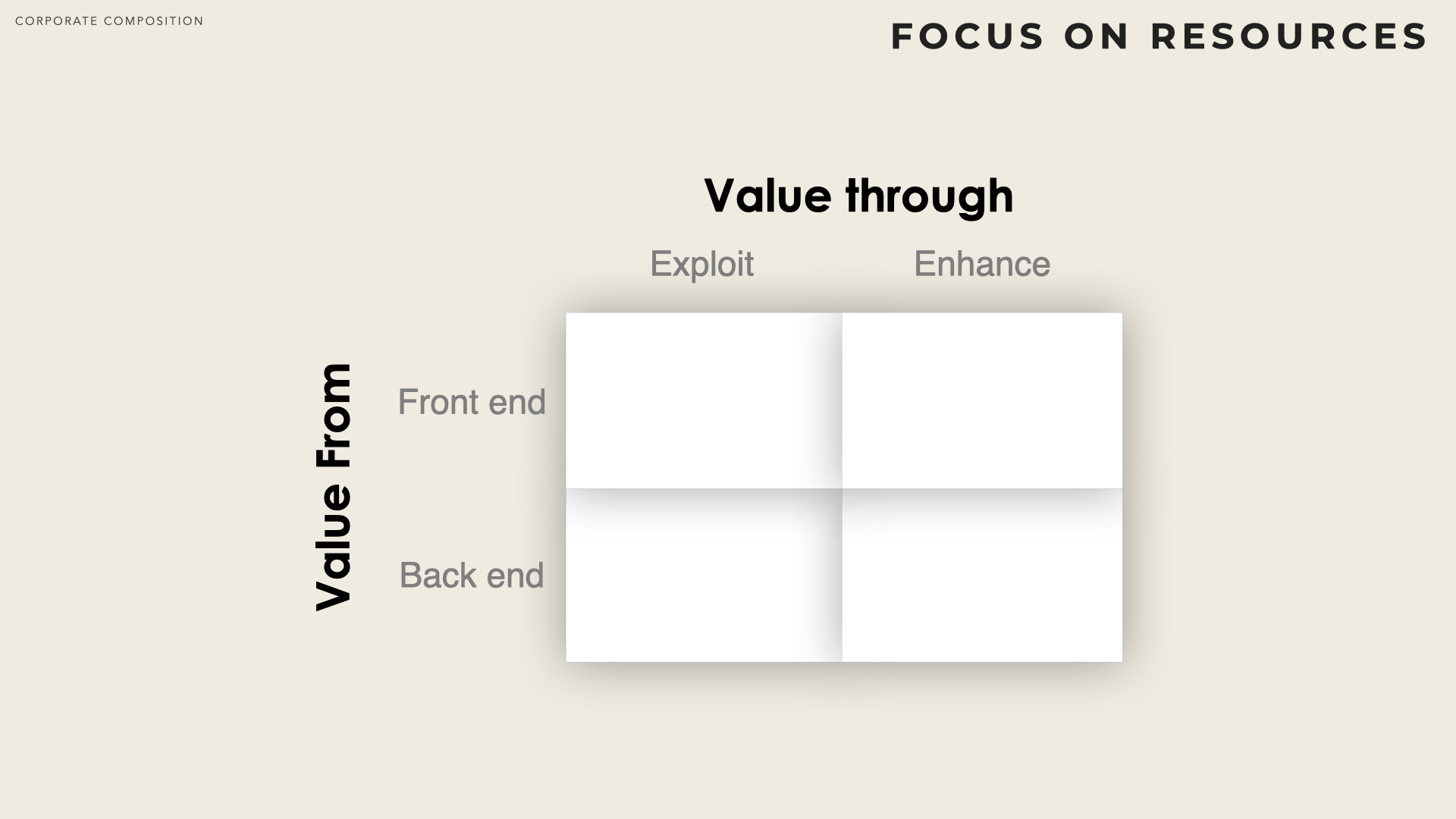

Organic Growth: exploit and enhance existing capabilities

For the purpose of corporate strategy formulation, existing resources can be thought as being of two kinds:

Front-end resources are directly used by the value proposition and often visible by end-customers (e.g. stores, layout, etc). Front-end capabilities also include market forecast, market development, marketing, etc.

Back-end resources are outside customers’ view and are more associated to production technologies (e.g. plants, machinery, patents). Backend capabilities also the information systems, production improvement means (e.g. lean management).

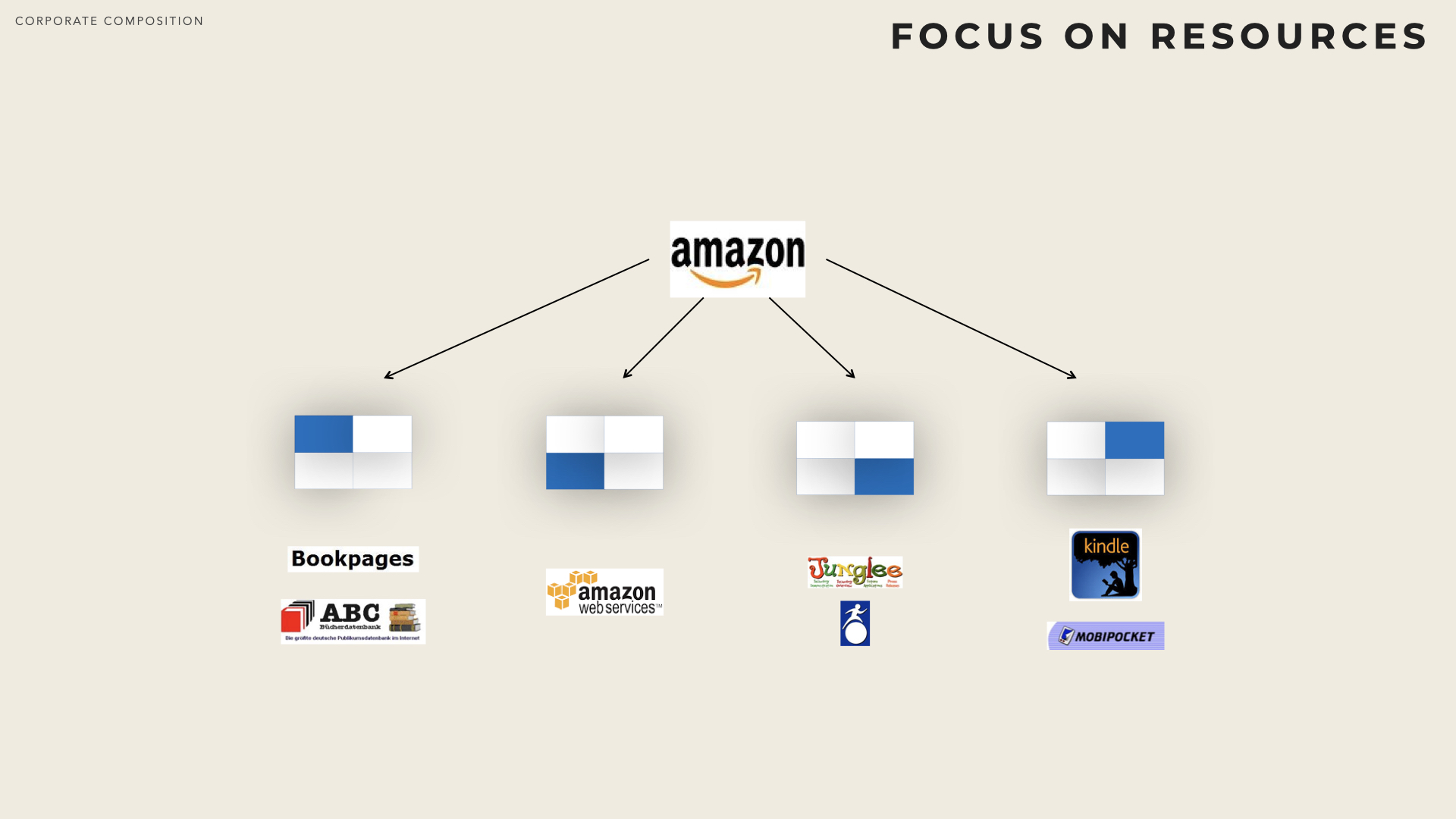

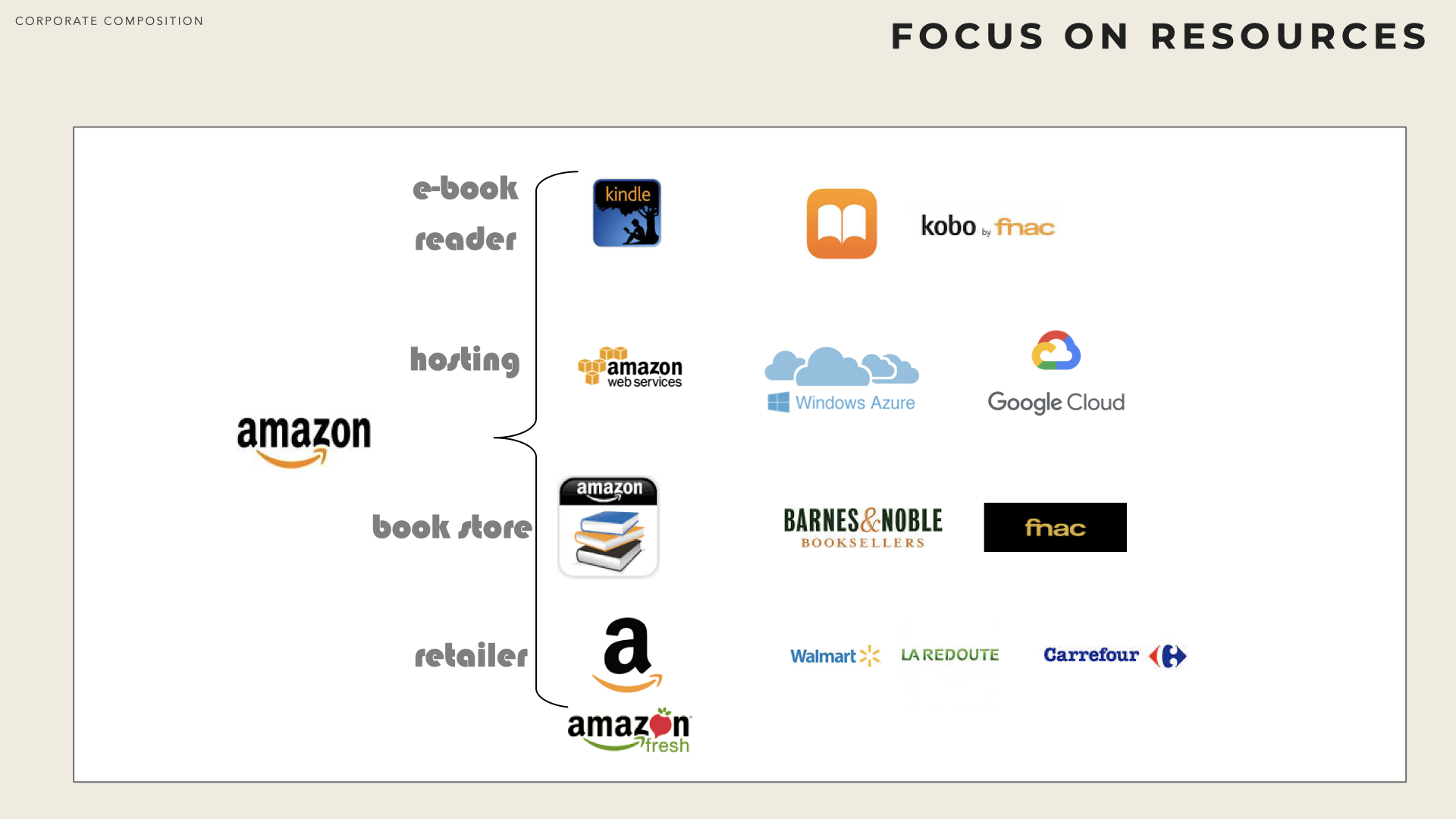

Let’s illustrate the exploit/enhance and back/front-end on Amazon’s case.

Exploit existing back-end resources

As Amazon developed its main business (on-line shopping) they acquired significant skills and competence in IT systems (web technologies, web servers, infrastructure). Initially all these capabilities were needed to support the main line of business.

However, in 2006 Amazon exploited these existing back-end capabilities and launched Amazon Web Services (AWS) which sells online services to others companies.

Enhance back-end resources

Amazon also grew its back-end capacity, for instance when they acquired Planet All and Jungle to provide better customer experience (personal information manager, reminder capabilities, advanced browsing features).

These capabilities supported the shift from book only toward more diversified product portfolio.

Exploit existing front-end resources

In 1998 Amazon bought the English bookseller ‘BookPages’ and the German bookseller ‘ABC’ (for their back-end capabilities). The two companies became amazon.uk and amazon.de respectively. These two acquisitions allowed Amazon to exploit its existing resources (i.e. deploy the existing web site) while generating additional value through market coverage extension.

In 2000 Amazon created the virtual market place (and offered to its customers to buy additional products supplied by third parties). This move also mainly corresponded to exploiting existing front-end resources (the web interface to customers and associated relationship management).

Enhance front-end resources

When Amazon brought Kindle to the market, it enhanced it Front-End capabilities.

As they appreciated that electronic books would represent a significant portion of their sales in the future. They also acquired Mobipocket (2005) a book producer and Brillance (2007) and audio-book producer.

The Parenting Advantage

According to Alexander, Campbell and Goold ( [Campbell95] ) one of the core question in corporate strategy is whether or not the corporate (the parent company) brings value to the businesses it owns.

A parent company sits between the shareholders and the various businesses it owns. As such, it reduces the leeway of both the shareholders and the businesses and induces additional costs. A multi business parent creates value (for the shareholders) if the various businesses perform better in aggregate than they would as a series of individual stand-alone entities. In addition, parents should strive to create more value out of their portfolio than could be achieved by any rival (other parent company, investment fund, shareholders).

Corporate strategy triggers two major decisions:

Parent’s characteristics how the parent should influence its business ? ”what organisational structure, management processes, and philosophy will foster superior performance from its businesses ?” Successful parents focus on a small and internally consistent set of insights that enable them to become the specialists: they are clear about their own roles.

Portfolio What businesses should this company, rather than rival companies, own and why ? What should be added, split off or sold ? To optimise value, the parent must select the businesses so that there is a fit between the parent’s characteristics and the most significant business improvement opportunities.

Value creation Value destruction trade-off

Alexander, Campbell and Goold have coined parenting advantage the ability of a parent to create value. They consider that two conditions are necessary for a parent to provide value to its businesses:

the corporate executives must deeply understand and feel the business of their businesses

the parent must have some competences or resources that is specially helpful to its business (there must be room for improvement and the parent must be helpful). Moreover they stressed that “the fit between parent and businesses is a two-edged sword: a good fit can create additional value; a bad one can destroy value”.

According to them, there are several sources of value destruction:

Standalone influence parents are involved in “agreeing and monitoring performance targets in approving major capital expenditures and in selecting the business unit managing directors”. However, parents often also interfere more deeply in product policy, marketing or human resources matters. The authors illustrate the bad influence of parents with the example of oil companies that all sought to diversify into minerals arguing that they mastered the skills and competences in natural resource exploration and extraction. There are however, many subtle differences between the oil business and the minerals and despite similarities, the two businesses relies on very different critical success factors. Corporate executives - all oil business veterans - pushed their mineral units to make poor (or sometimes bad) decisions. “The corporate executives couldn’t really get to grips with the mineral business, they couldn’t feel it”. After ten years of unsuccessful experience, oil companies have divested their minerals businesses. Usually the executive running the business are better informed / knowledgeable about their business than the parent executives.

Linkage influence a corporate parent may seek to foster synergies across its various business. More often than not, the costs of establishing common systems and services out weight the benefit of sharing. Global processes (e.g. cross selling) require additional layers of coordinations and the overhead costs are not always compensated by additional sales.

Central Function & Services establishing central services (common to several or all the units and managed centrally by the head quarter) usually implies increasing overhead costs, increasing response time and the deterioration of the quality of service as the function gets more remote from the business.

Corporate development Research indicates that the majority of Corporately sponsored acquisitions, alliances, new ventures and business redefinitions fail to create value.

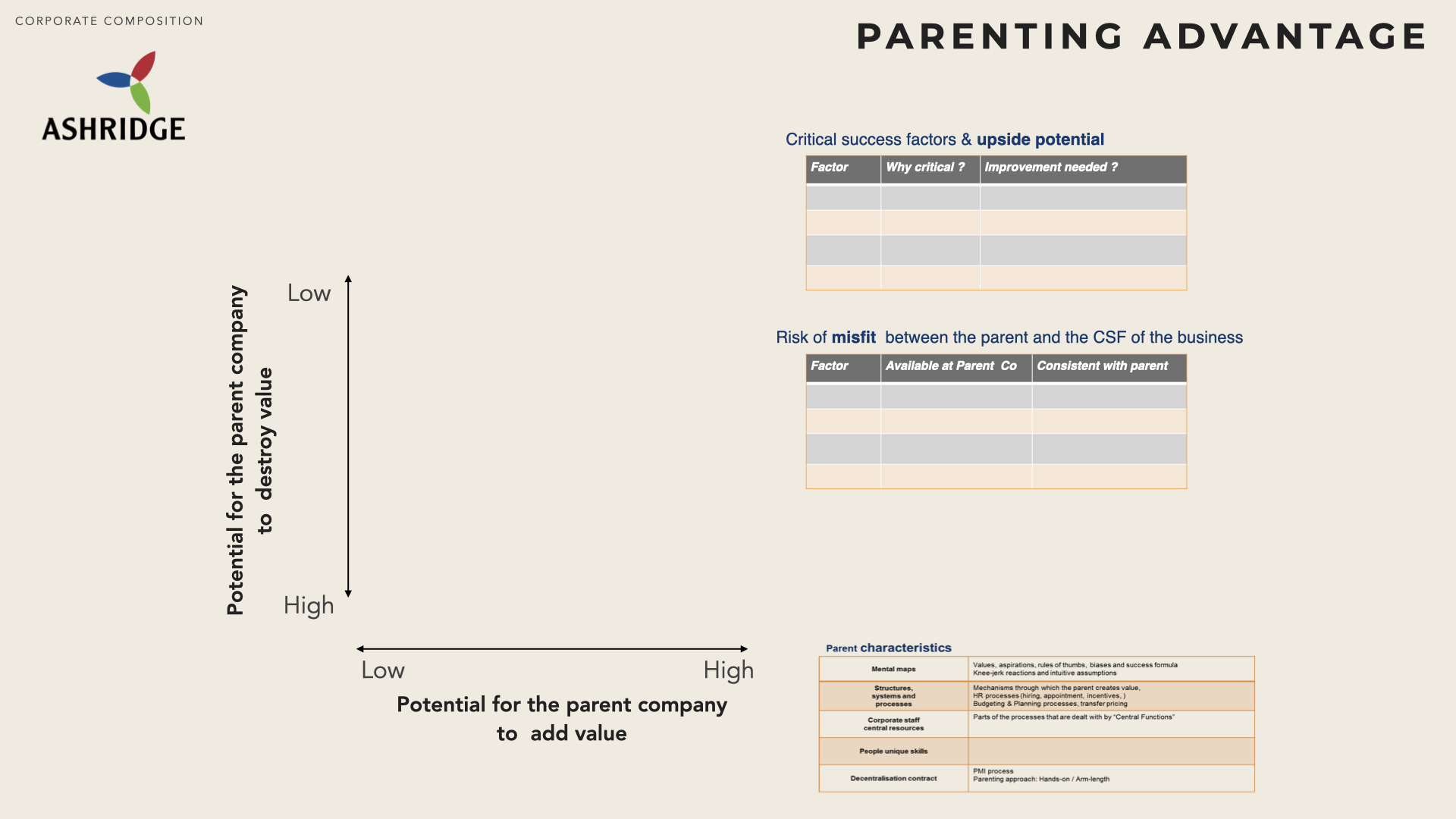

Assessing the parenting first

Assessing the fit between a parent company and its businesses is a critical but tough question. Alexander, Campell and Goold suggest that it should encompass the following steps:

Understanding the critical success factors for each and every business owned by the parent: what does it take to be successful? Each industry relies on a few activities or issues that are critical to performance. Furthermore a specific business may derive a competitive advantage (firm specific advantage) from a few characteristics. A parent can create value to a set of apparently non-related business, provided that the critical success factors are not too dissimilar.

Identify potential upsides the parent can only create value in businesses where there is room for improvement. It is therefore crucial to identify areas of improvement (potential parenting opportunities). Several sources of parenting opportunities are underlines in [Campbell et al., 1995b] : killing bureaucracy, providing financial resources, attracting and retaining top managers, improving marketing, streamlining production, economies of scale, shared and scarce expertise, lobbying and external relationships, etc. Most business could improve their performance if they had the parent with the adequate skills and abilities.

Delineate the characteristics of the parent in this step, the focus is on the capacities of the parent. What expertise, specific capabilities, differentiating skills can the parent bring to its businesses. According to [Campbell et al., 1995b] several characteristics must be taken into account. The parent’s mental maps encompass to the (often implicit) value of the parent, its biases, simplification principles and rules of thumb. The capability of a parent to truly understand and feel a specific business, often derives from its mental maps. The parenting structures that the parent usually deploy (management structure and layers, appointment principles, budgeting planning and investment approval system, governance and decision-making structures, etc.)

The corporate structure (specific staffs, departments at the headquarter, central functions and expertise) is also a key ingredient of parenting value creation. Last but not least the centralisation / decentralisation balance between the parent and its business defines the nature and perimeter of the influence the parent needs to have on its businesses.

Fit between the parent characteristics and the potential upsides once both the potential upsides and the characteristics of the parent have been revealed, it gets easier to appraise how much the parent can bring or conversely how penalising its influence can be. The parent that owns the proper characteristics (resources, skills, knowhow, behaviour) can exploit the upside potential of the businesses. By contrast, if the parent characteristics don’t fit with the business critical success factor, there is downside in the relationship with the business.

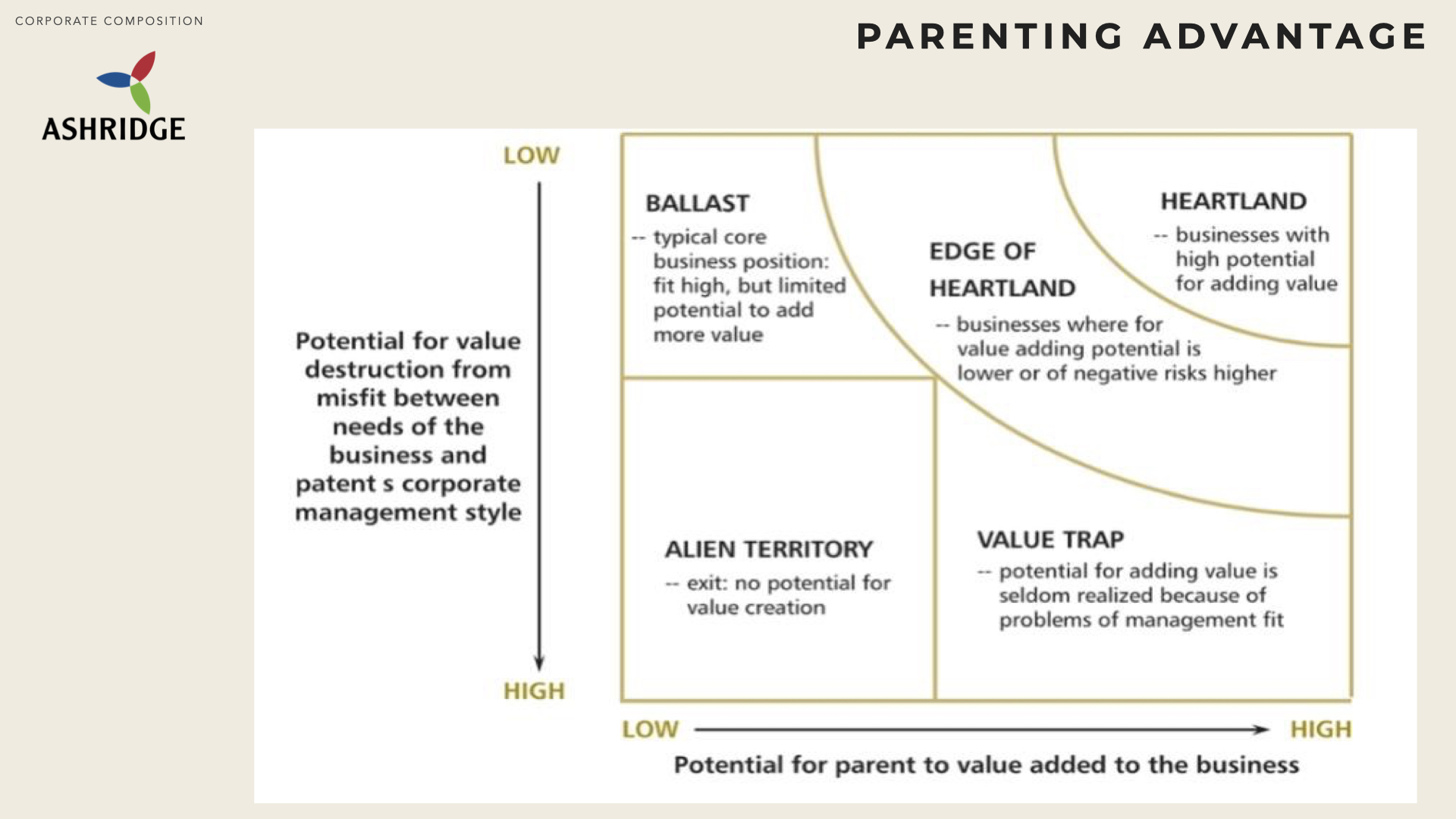

The parenting Matrix

The parenting matrix is built along two axes:

how well the parent fits the business upside opportunities

how well the parent characteristics fits critical success factors of the business.

In other words, how much the parent can help the business and how much it understands and feels the business.

Heartland businesses correspond to businesses where the parent both can improve the performance and deeply understand the critical success factors. Ideally, all the businesses in a group should be “heartland” businesses.

Edge of Heartland some parenting characteristics fit but not all. Value creation is partly offset by elements that fit less and can destroy value (at least lack value creation potential). The net contribution to value is not clear-cut.

Ballast businesses the parent understands the business extremely well and is very comfortable with the business. The parent doesn’t have however the right characteristics to help the business improve its performance. A more adequate parent would create more value. In addition, there is a danger that a change in the business environment can move a ballast business into an alien-territory business.

Alien-Territory businesses correspond to businesses for which the parent can’t help improve performance and in addition, the parent characteristics don’t fit with the critical success factors. This is the typical area where the parent destroy value.

Value Trap businesses this is the areas where parent executives have the worst influence and make the biggest mistakes. They are business with a fit in parenting opportunity and a misfit in critical success factors. Businesses in this area can receive positive support from their parent company. However the parent executive fail to truly understand the business environment and priority. “The potential for upside gains blinds managers to downside risks”.

A. Parenting Value Adding & Destroying

Typical value adding capabilities that can be brought by a parent company include:

Envisioning clear overall vision and strategic intend for its business units

Coaching assist BU managers in developing strategic capabilities, facilitate sharing among units. Corporate-wide training is usually one of the effective means to foster cooperation among BUs.

Providing Central Service - either centralise capital investment and/or provide shared services such as HR, Legal, Communication, Information Services.

Intervening closely monitor performance of the BUs and assist or re- place weak managers when performance doesn’t meet the targets.

There are also circumstances where a parent destroys value:

Adding overhead Costs staff& facilities of the corporate centre(i.e.HQ) can be expensive while not producing any revenues.

Adding bureaucratic complexity reporting, additional management layers Averaging effect - when monitoring isn’t robust enough or transparent, weak under-performing businesses can survive longer.

B. Corporate Parenting roles

There are three main archetypes of parenting role.

The portfolio manager is acting as an “agent” on behalf of the financial mar- kets. Such a parent company doesn’t get closely involved in the routine management of the various businesses, except over short period of time to improve performance. The parent company concentrate on providing (respectively withdrawing) capital investments. The CEOs of the BUs enjoy a high degree of autonomy but are given clear performance targets (with high reward in case targets are met and the risk to loose their position otherwise). The parent company periodically make evaluation about the well-being and future prospect of the businesses and review its investing/divesting schemes accordingly.

The synergy manager is a parent company seeking to generate value by in- creasing synergies among its BUs. It heavily relies on envisioning to create a common purpose. It also facilitate and foster cooperation among BUs. More often than not the parent company will seek to provide shared services to in- crease as much as feasible synergies. There is the risk of illusory synergies (i.e. synergies that are claimed but never materialise).

The parental developer is a parent company that seeks to leverage its own central capabilities to add value to its businesses. It typically focuses on resources it owns as a parent and on how to transfer downward to BUs (rather than on how to foster synergies across BUs).